This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

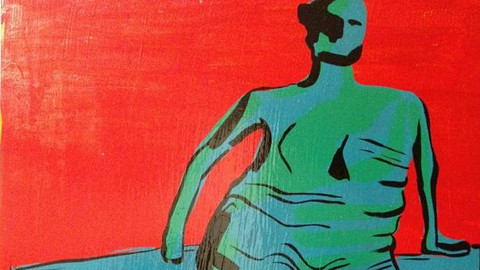

On a rather gloomy January evening, the Tate Britain Clore lecture theatre provided welcome shelter from the inclement weather and more importantly, a venue for a timely debate about the future of public art in the UK. The gloriously rotund and proud figure of Henry Moore’s Old Flo loomed large in the room, and Tate Britain director Penelope Curtis, acting as compere for the evening, opened the event by reminding the audience of the reams of press coverage devoted to the uncertain future of Moore’s bronze beauty.

The case of Old Flo and the attempts by Tower Hamlets council to sell her (she is currently on display at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park and has been for the last fifteen years or so when she lost her original home on the now demolished Stifford estate in east London) underpinned much of the evening’s debate and it is likely many attendees left buzzing with more questions than answers or solutions as to how to secure twentieth century sculpture from action driven by short-termism.

Robert Burstow, Reader in History and Theory of Art at the University of Derby, with a particular interest modern sculpture in post-war Britain, provided some scene setting. He took the audience back to the optimism felt in Britain immediately after the second world war, underpinned by a nation eager for a new and modern identity. The creation of inspiring public spaces and art was bound up in the emergence of an accessible, democratised idea of ‘recreation’, most obviously displayed at Battersea Park (1948) and in 1951 on the South Bank. Increasingly, particularly as part of the New Town expansion, councils took inspiration from to the London County Council (LCC) and acquired works of art for all different types of municipal and residential buildings. Hopeful ‘art with heart’ began to appear.

A very polite Simon Parker of the New Local Government Network was next up. Perhaps Parker anticipated a rough ride from the Tate audience given that he has publicly argued that the sale of Old Flo would not necessarily make Tower Hamlets the cultural vandals’ opponents of the sale suggest. He pleaded personal appreciation for the ‘difficulty’ of the Old Flo situation, praised what the LCC did for public arts and spaces, but then naturally relayed the current austerity messages, referencing the comically titled (if it wasn’t so damn depressing) Graph of Doom. According to Parker we mustn’t fall into the trap of thinking that local government decision-makers clap their hands in glee at the prospect of ‘asset stripping’. No, they take it very seriously. In many cases, I’m sure that’s spot on and of course the ‘workers’ who have to execute decisions made by those in the council chamber are under huge pressure. A thoughtful sounding employee of Birmingham City Council culture services (which must surely be feeling exposed) asked whether the de-commissioning of public art works was ever acceptable. Maybe. Perhaps it would be sensible for all local authorities to have a well-considered de-commissioning policy in place against which individual cases can be assessed? That said, there couldn’t be a worse time for authorities to create such a policy, written in the heat of austerity and cuts. But if not now – then when?

Parker’s general sentiments left me feeling distinctly depressed. Some of his points merited further thought ie. political leaders must genuinely try to get to the root of the inspirational capacity of culture and use it to motivate people (his example of a former Mayor of Bogator, Antanas Mockus, who used ‘art as leadership’ was fun although I don’t see our current administration applying such tactics). However, is was his point that its not that bleak an outlook for culture in local authorities (well, unless you are a Newcastle resident who is partial to a bit of art) – no, not in comparison to the impact of the cuts on planning services. Planning is the prime target, all part of Pickles progress. Well, that’s ok then….Personally, this worries me hugely – so much can fall under the ‘planning’ umbrella – and conservation services are especially vulnerable.

Are we in a post 1945 position all over again, just without the optimism and vision?

Parker professed himself a ‘localist’, naturally. There was a general murmur around the room that should Flo be sold and Tower Hamlets receive the swag (incidentally, the issue of ownership continues to be debated by lawyers across all of the big organisations with an interest in the case) would it be wisely (definition of which, please?) re-invested in the people of Tower Hamlets as the council press office assert? I thought I heard someone say that a Henry Moore centre had been suggested for the borough, but I really hope the Clore’s acoustics deceived my ears. The irony of such an idea while Flo would be ready and willing to return home for far less cost is, well, ironic. Is this localism?

To lift the spirits of the assembled, Bob of Bob and Roberta Smith, took to the stage with a rallying cry that to lose the public sculpture of the post war period would be to lose the embodiment of democracy and hope, vital to inform future generations (or, in summary, ‘we must f*cking hang on to them’). Emotional stuff perhaps, but with real, meaty, grains of truth. The loss of Old Flo to private hands, possibly outside of the UK is, Bob suggests, akin to smashing up war memorials. Moore intended Flo as a symbol of resilience against fascist pressure, so Bob’s point is more than valid. And I guess that because Flo represents the east London ‘everywomen’, even without Stifford, she would offer a valuable presence in this part of the capital again.

Auction house Christie’s also came in for a knocking – for wildly overestimating Flo’s likely financial value. A figure (£20million) was joyfully chucked around by the media, helping to underline the case for proponents of the sale (‘people more important than objects – think what £20million could do’ etc etc).

Bob has been heavily involved in the Old Flo campaign, working with the Museum of London, who’ve offered Flo a home outside their Docklands museum (to no response from the Tower Hamlets mayor), a free site, popular with borough residents, and in particular, families. Bob and BBC London went on walkabouts in Poplar looking for local opinions on Flo. The great majority were warm to the idea of the sculpture being displayed in borough. That said, a greater number didn’t know Flo existed in the first place. She was not relevant to them. The idea mooted in the room that greater interpretation of public art works would be one way of securing them against rash action seems valuable (although who take this task on or ensure it was embedded in to future commissions, wasn’t clear). I wonder if there was any reference to Flo and her once presence – and what she signified – in the borough after she left for Yorkshire? Probably not – no wonder people feel apathy. In attendance, the Public Monuments and Sculpture Association lamented that there is no audit of the country’s public art, so the picture of our open-air national gallery is hazy and, as a result, at risk. This could be corrected if relevant organisations worked together to create a catalogue of post war public art – ambitious but doable. It would provide an invaluable foundation and could offer real potential for you and I to get involved as local knowledge about public art works could inform records.

I was not surprised to hear someone suggesting that putting a financial value against our public art would surely give it the merit that decision makers and politicians could understand. It’s a fine theory – but in my opinion, just that, a theory. May I be so bold to suggest that bodies such as English Heritage (EH) have been compelled by successive administrations over the past 15 years to ‘show us the money’ ie the financial contribution of the built environment. Energy, time, and resources have been thrown (sorry, invested) in doing exactly that and it appears as though it’s been for nought given the ringer EH is being put through, plus the increasing pressure descending on historic environment services at local level.

Perhaps our perception of what public art is, and can be, needs to evolve – should we embrace temporary, ephemeral public works over the permanent? Our urban landscapes are increasingly vulnerable to privately funded sculpture, while nervous local authorities either commission coyly, within safe parameters of what they think local people will ‘accept’ (never mind embrace), or not at all. There are of course blindingly good examples of ‘corporate’ art, just look to Broadgate Square in the City of London (although not for long perhaps – a Certificate of Immunity from Listing has been issued for more of the development, as well as the sculptures ‘Leaping Hare on Crescent and Bell’ and ‘Fulcrum’, the associated paving and landscaping).

So, Flo, I’m sorry, I don’t know what the future holds for you and your contemporaries, but it’s likely that there will be other battles ahead. As we know, there is risk in the recent – not old enough to be perceived as traditional heritage and not new enough to qualify as contemporary – a no man’s land. In this weird time of austerity it’s down to you and I to impress on authorities how we feel about public art – a risky strategy, but right now, it’s probably all we’ve got.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.

Comments