This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

January 2004 - Dudley Zoo

Tecton and Berthold Lubetkin (1901-1990)’s roles in the history of British modernism have long been recognised, yet not all of their work receives the attention that it deserves. Far removed from the London-centric sphere of cultural consciousness, Dudley Zoo (1935-37) is one such work, a neglected monument of national significance. The Tecton practice’s zoo buildings at London, Dudley and Whipsnade introduced modernism to a mass audience and attained a degree of popularity and face-to-face exposure that other architects could only have dreamed of. The twelve surviving pavilions at Dudley are more than worthy of comparison with their better-known London precursor, London Zoo’s Penguin Pool (1933-34), and represent a unique collection of works by an early modernist practice on one site.

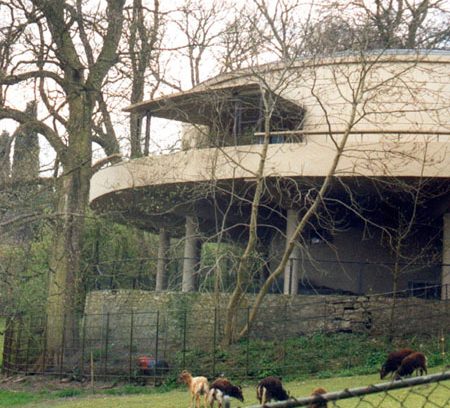

Arriving at Dudley Zoo today is not an auspicious event. From the car park behind Gala Bingo, visitors pass a decrepit nightclub in the cannibalised remains of one of Tecton’s original cafeterias. Although the festive entrance canopies are in good condition, they no longer serve as the entrance. Visitors are instead corralled through a narrow passageway into the uninviting realms of the zoo shop. There they are invited to buy stuffed animals and colouring pads, but no time or space is given to drawing peoples’ attention to the Zoo’s most remarkable exhibits – its buildings. Finding the enclosures is made more difficult by the sixty odd additions made since the opening, none of which makes any pretence to architectural merit. As one explores the site and the twelve surviving buildings do begin to appear, there is the sense of discovering lost treasures. Several stand as significant works in their own right, while as a group they have no parallel. Foremost amongst them are the Bear Ravine, Polar Bear Pit and Birdhouse, all of which survive in relatively good condition. Others, such as Dudley’s own Penguin Pool and the Moat Café have been demolished or altered beyond recognition.

The picture when the Zoo opened in the winter of 1937 would have been somewhat different. Assuming they had beaten the throng of thousands to gain entry, a visitor arriving on that first day would have found the thirteen original pavilions loosely scattered within the pristine setting of the castle mound. Dudley allowed Tecton many of the freedoms of a student project and working closely with Ove Arup, they continued to explore their fascination with the structural and sculptural potential of concrete. Tecton designed the enclosures in such a way as to emphasise the steep inclines and densely wooded slopes. They clearly relished the dramatic potential that the site provided but also respected its natural beauty and calm. Using the existing roads and pathways to stitch the buildings into their context, Tecton created an overall composition reminiscent of an English landscape garden, but they were also clearly conscious of the urban implications of what they doing. Just as some had seen the London Penguin Pool as a prototype of a futuristic house, so Dudley can be interpreted as a blueprint for an entire city. As the put it, the new Zoo would be: “at once a scientific centre and an example of an ultra-modern town plan.”

Berthold Lubetkin once said: “I have the unfashionable conviction that the proper concern of architecture is more than self-display. It is a thesis, a declaration, a statement of the social aims of the age.” Encapsulated in the playful pavilions at Dudley is a call to remember the higher calling of all architecture, embracing not just material needs but also the desire to inspire and delight. Dudley Zoo did not change the world but it does stand as a monument to a vision of an alternative modernism. As with much of Tecton’s work, it seems to anticipate a more relaxed and joyful approach to form and function. It is not the dour, one-size-fits all architecture that came to epitomise so much of post-war Britain , but rather a unique, three-dimensional manifesto, written in concrete, for an enjoyable and humane urban future.

Dudley Council is currently planning a major redevelopment of the castle mound and zoo site. Working with the developer St Modwen, they hope to use the project as a spur to wider regeneration. After criticism of initial plans that proposed reducing the size of the Zoo, they are now talking about an expanded zoological and environmental theme park. While mention has been made of integrating the listed Tecton buildings, the developers only pay lip-service to their importance and appear blind to their potential as architectural attractions. John Allan’s extensive survey and restoration proposals of the early nineties have been long forgotten and in the absence of a clear strategy for preserving and promoting the enclosures, it seems that they are destined to linger on in a forlorn and neglected state. At a time of growing appreciation for modern architecture it seems perverse that one of the country’s best early modern sites continues to exist in obscurity and neglect. Sadly, recent precedents for buildings of this period are not good and all the signs indicate the decades of indifference displayed towards one of this country’s prime architectural sites is set to continue.

Dudley Zoo is situated at 2 The Broadway, Dudley, West Midlands . By car, it is can be reached on the A461 (Castle Hill), 3 miles from M5 Junction 2; Dudley Bus Station is 2 minutes walk from the Zoo entrance; Dudley Port rail station and Coseley rail station are both 3 miles away. For information on opening times telephone ( 01384) 215313.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.