This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

Photo courtesy of Colvin & Moggridge

We welcome the move by Historic England to add 20 post war parks, gardens and landscapes to the protected national register but are disappointed that the review has not gone far enough.

Catherine Croft, Director of the C20 Society, said: “This is an excellent piece of research, but a huge wealth of equally good examples remain unprotected and the most difficult types of sites have been sidestepped by this review. None of the few remaining majestic groups of concrete cooling towers are included, and soon none of these will be left standing. Nor is the skill and care brought to the very best road schemes acknowledged.”

Of the 1,600 sites on the national landscapes register, only 24 were from 1950-1999, so it is good news that the significance of landscape design of this period is now being better appreciated and that more sites are being protected as an important record of British life, just as much as the gardens and landscapes of earlier centuries. The newly announced protections are the result of a three-year collaboration with The Gardens Trust.

We are particularly pleased that the landscapes of seven post war housing estates have been included and are hopeful that the addition of Alton East and Alton West in Roehampton at Grade II will give the council reason to pause in its plans to redevelop the site. But it is disappointing that the threatened London estates of Central Hill and Cressingham Gardens which came under the remit of Ted Hollamby at Lambeth Council have not been given protection.

Photo: courtesy Thaddeus Zupancic

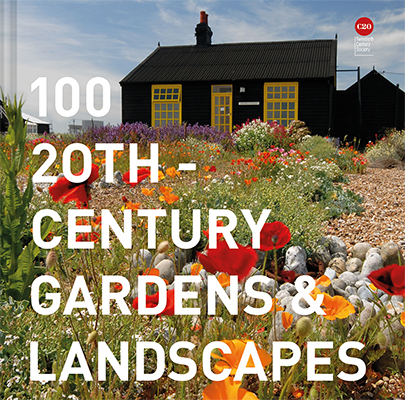

Many of the landscapes which have been added to the register are featured in C20 Society’s new book ‘100 20th Century Gardens & Landscapes’ (edited by Susannah Charlton and Elain Harwood and published by Batsford, RRP £25) which traces the evolution of gardens and landscapes over the past century, looking at how they complemented buildings of their period.

The 20th century was also eclectic and radical in bringing the landscape architect’s vision to places never before considered and the book studies how thoughtful landscaping has successfully integrated vital industrial facilities into sensitive landscapes and also rehabilitated some of the most contaminated post-industrial sites in Britain.

Examples include Eggborough Power Station (1961-73), in Goole, North Yorkshire, where landscape architect Brenda Colvin framed the huge buildings in long shelter belts on raised banks, within which, near the cooling towers she placed recreation landscapes for the power station staff. West Burton Power Station (1961-69) in Nottingham can be considered as a key example of Nikolaus Pevsner’s post war argument for the use of picturesque principles as a modern concern, where a new power station could be organised within a landscape, rather than being idealised or excluded altogether

At Trawsfynydd Power Station (1959-65), in Gwynedd, Snowdonia, Sylvia Crowe aimed to achieve ‘scale domination’ within an open landscape, incorporating an expansive body of water – created in the 1920s to supply water for the Maentwrog hydro-electric power station – and carefully selected tree planting. The collaboration between herself and Basil Spence has been likened to that of gardener and architect found in 18th-century landscapes. They intended the main buildings to be seen in the same spirit as a medieval castle.

Photo: John East

The landscaping of Hope Cement Works, now Breedon Group, (1943) Castleton, Derbyshire, was designed by Geoffrey Jellicoe, whose decision to respect, even aggrandise, the strongly marked valley and hill landscape gave it staying power. He kept the line of the escarpment inviolate, but gave the quarry a high lip from which banks of waste have collected on either side, now planted with trees. Lakes formed by the excavation of clay from the valley floor are now a nature reserve.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.