This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

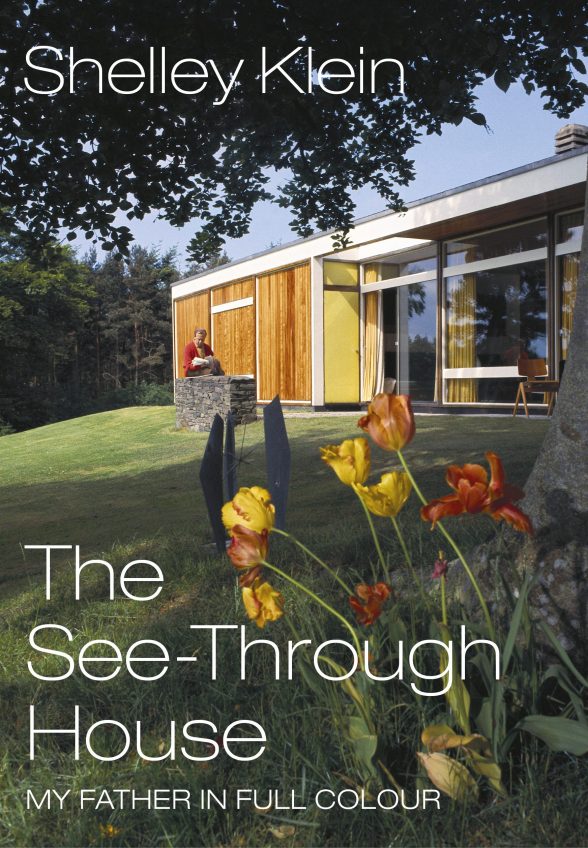

The See-Through House: My Father in Full Colour

Shelley Klein, (Chatto & Windus, 288pp, £16.99)

Reviewed by Neil Jackson

April 2020

It can’t be often that Radio 4’s ‘Book of the Week’ features a book about a modern house, but The See-Through House was the programme’s choice in May this year. Although it is a book about Shelley Klein’s father, the textile designer Bernat Klein, it is as much about the modern house which, in 1957, the architect Peter Womersley had built for Klein just outside Selkirk, in the Scottish Borders. It was at High Sunderland that Shelley Klein had grown up and it was there that she returned, a year after her mother’s death, to help her 85-year-old father.

Bernat Klein, or Beri, was, as Shelley says, one of the kindest, most generous men she knew, but he was also one of the most difficult, and it is the tension between the father and daughter, expressed theatrically as stage dialogue, which gives this book so much life. From the opening argument, ten minutes after her arrival, concerning her battered Victorian chair which Beri thought ‘GHASTLY’, to his banning of her potted herbs from the kitchen because they spoiled the line of the house, the presence of the architecture as the determinant of a lifestyle is apparent. The house set the rules and Beri enforced them, for like the warp and the weft of one of his tweeds, the two were inextricably linked.

The book is arranged as the house was, each chapter describing a room while also digressing to include reminiscences, such as Beri’s childhood in Senta (now in Serbia), or his education in an Orthodox Jewish yeshiva in Jerusalem. Beri’s mother, Zori, as well as many of his relatives, were ‘murdered’ (Shelley’s inverted commas) at Auschwitz, but his father, Lipot, and his brother, Moshe, survived. However, Beri rejected his Judaism and studied textiles at Leeds University where he met Peggy, whom he later married. Textiles had been the family business in Senta and it was the textile industry which drew him to the Scottish Borders which Womersley (another Borders immigrant) described as a ‘superb landscape to live in.’ Beri could feel colour, and it was the colours of the Borders that he worked into his palette-knife paintings and wove into the fabric which Coco Chanel chose for her 1963 spring collection, as well as those which Pierre Cardin, Christian Dior, Louis Féraud, Guy Karoche, Nini Ricci, Yves Saint Laurant and Hardy Amies all took up that autumn. Soon elegant models, flown in from London, paraded along the raised library walkway at High Sunderland, at the end of which was the area Womersley designated as a ‘study’, where Beri would sit, working on colour samples. Here light penetrated the building, as it did all around, for it was indeed a see-through house, an open-plan assemblage of timber-frame construction, glazed walls and floating panels of colour. Sadly, this transparency and lightness is totally lost in the diagrammatic plan included in the book, where the line-weight fails to discriminate between boarded and glazed walls, or even between walls and changes in floor level and finish.

Shelley remained in the see-through house for four years after her father died in 2014, her depression and grieving becoming deeper, and unable to tell which was which. Although Beri had died he had not gone away, for he was the see-through house and the see-through house was him. Striking matches, she half-intended to burn it down: like Peggy five years before him, Beri too had been cremated. It is indeed fortunate that she failed to do so.

We are still populating our book review section. You will be able to search by book name, author or date of publication.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.