This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

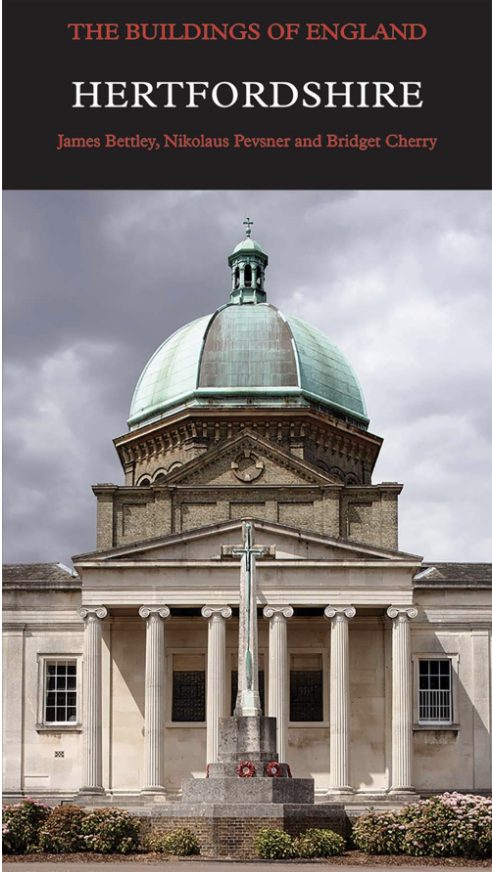

The Buildings of England: Hertfordshire

James Bettley, Nikolaus Pevsner and Bridget Cherry (Yale University Press, 804pp, £35)

Reviewed by Elain Harwood

March 2019

Unfamiliar with the south-east before my twenties, Stevie Smith’s paean to the county took me by surprise. ‘Hertfordshire is my love, it is so un-exciting, so quiet, its woods so thick and abominably drained, so pashy underneath…’ Over the Frontier was published in 1938, when Smith described Hertfordshire as north London’s playground. Whereas Surrey had been opened up to commuters by trains in the nineteenth century, Hertfordshire only began to be developed in the twentieth, and its countryside remains protectively rural. Bettley’s revision of Pevsner’s Buildings of England: Hertfordshire is astute and assured, as confident of the county’s C20 century heritage as of its earlier buildings. This is important, since this must be the richest county of our period outside London. Hertfordshire has many fine private houses from the 1930s by major architects: Connell, Ward and Lucas at Moor Park, Maxwell Fry at Chipperfield, F R S Yorke at Nast Hyde and Mary Crowley at Tewin. The post-war years added more, including many by architects for themselves or close friends: David and Mary Medd at Digswell, Alison & Peter Smithson at Watford, Jack Bonnington and Povl Ahm (from a sketch by Jørn Utzon) at Harpenden, and George Marsh at Radlett. Bettley identifies less well-known houses for architects in Stevenage, and by Peter Boston in Harpenden and Ashwell, as well as houses by Piers Gough and James Gorst from the 1980s.

But Hertfordshire has one outstanding claim to fame: the founding of the Garden City movement, first with Letchworth in 1903 and then Welwyn Garden City in 1919 – the area’s remote nature revealed in that the population then stood at just 400 souls. Letchworth moved from quirky Arts & Crafts towards neo-Georgian in its public buildings either side of 1914, but Welwyn plumped firmly and distinctively for the latter, though Bettley points to a handful of Modern Movement houses worthy of exploration.

The garden cities put Herts on the international map, but are also important for begetting England’s new towns. By 1945 planners were keen to exploit the transport links between London, the Midlands and north, making Hertfordshire the centre for the wave of new towns where the government concentrated its building efforts after the war. Pevsner was sympathetic to the understated modernism of the 1940s and 1950s; his revisers are often less so. So, to apply the Harwood litmus test of all revisions: the descriptions of new towns. Bettley gives adroit descriptions of the first one, Stevenage, with its taut and finely detailed shopping precinct, now being attacked by new development; the industrial area, with its warehouse engineered by Felix Candela and building for the Furniture Industry Research Association by HKPA; and neighbourhoods of low-rise terraced housing around small greens, of which the first to separate pedestrian and parking areas was the most imaginative, at Brontë and Austen Paths from 1959–62. He gives due mention to the ambitious cycle paths introduced by the cycling engineer, Eric Claxton, rather less to the sculpture by local artists. Sculpture gets a better look-in at the more complex additions at Hemel Hempstead, already a large town before being designated under the New Town Act of 1946. It had built its thousandth home by 1952, setting it ahead of all the others, as drainage works already existed; it therefore became the target of the attacks on prairie planning led by J M Richards a year later. Hertfordshire has one other claim to fame. In a county with fine public buildings, the outstanding achievement was its schools programme. With such an exodus to the county, matched by a rising birth rate, a new school was needed every month in the 1940s. The county council, led by deputy architect Stirrat Johnson-Marshall, adopted a programme of prefabrication, creating a kit of parts and a three-dimensional grid that allowed every building to be adapted to its surroundings. Child-sized fittings and artwork added to the charm. When schools everywhere else disappeared in the 2000s, Hertfordshire recognised the quality of what it had. Bettley is also sympathetic to the pioneering technical college by Easton & Robertson at Hatfield, now the University of Hertfordshire.With so much C20 architecture, Hertfordshire had to be a special volume, and it is good to report that Bettley has risen to the challenge, as Bridget Cherry did before him.

We are still populating our book review section. You will be able to search by book name, author or date of publication.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.