This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

Credit: Richard Learoyd

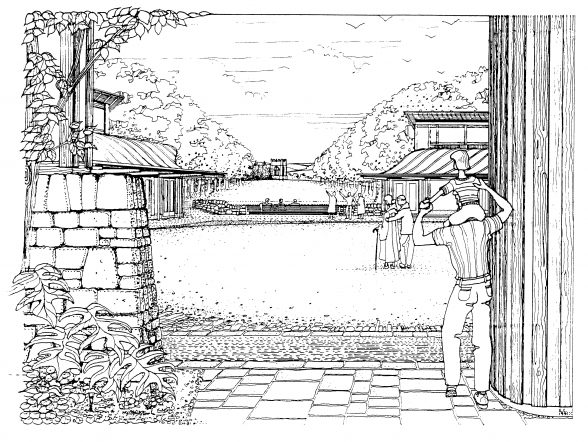

September 2021 - Fountains Abbey Visitor Centre, Ripon

Ted Cullinan, 1992

Ted Cullinan first visited the great Georgian landscape park of Studley Royal in Yorkshire as a schoolboy. Evacuated to Canada with his mother and siblings at the age of eight, on the outbreak of the Second World War, he returned in 1943 on a Royal Navy cruiser. (The tortuous journey, via New York and Bermuda, took three months.) He was bound for Ampleforth, the Roman Catholic public school, run by Benedictines, which has the fine abbey church by Giles Gilbert Scott, then only half-completed, at its heart. Cullinan, still deeply religious, found school life trying but became a rather good rugger player. Whenever he could he spent time in the art room. The art master, Father Raphael, took his pupils on sketching and water-colouring expeditions and one of these was to Studley Royal, the landscape created by John Aislabie (1670-1742).

Credit: Cullinan Studio

The park was then in a melancholy state of decay – it passed to the West Riding County Council in the 1960s and to the National Trust in 1983. At the end of the long run of lakes, canals and cascades that form one of the most remarkable man-made landscapes in Britain were the extensive ruins of Fountains Abbey, its church roofless but otherwise intact. There had been ideas, never very practical, of the Benedictines acquiring Fountains, restoring the ruins and installing a community of monks there. These faded in the postwar years, but the abbey made a strong impression on Cullinan.

Credit: Cullinan Studio

Credit: Martin Charles

With up to 400,000 visitors a year, Studley Royal had become, by the 1980s, one of the National Trust’s most popular properties, but visitor facilities were far from generous and parking – most visitors arrived by car – was at a premium. The favoured solution was to build a visitor centre, one of a number being commissioned by the Trust in the Eighties, on high ground north of, but within a short distance from, the abbey ruins. The site was accessible via the Ripon to Pateley Bridge road. The National Trust was growing fast – in ten years its membership had doubled. It had attracted inspired leadership – Dame Jennifer Jenkins became its chairman in 1986 and the Yorkshire region had a chairman (Sir Marcus Worsley) and a director (John Garrett) who were enthusiastic about the visitor centre project. Back in London, the Trust’s historic buildings secretary, Martin Drury, argued that the project should produce an outstanding work of contemporary architecture. Cullinan’s appointment came in 1987, but his first ideas for the centre, for a compact building on a cruciform plan, a true “gateway”, straddling the path from the car park to the abbey, was rejected on the grounds that the new building could be glimpsed from the abbey and a second option, involving the conversion and extension of nearby farm buildings, also failed to find favour. The built scheme pushed the centre further back from the valley edge, removing the chance of a striking dialogue between old and new.

Nonetheless major elements of the first scheme, the use of dry-stone walling, with a timber superstructure, were retained in the centre as built, though Cullinan’s suggested roof covering of clay pantiles, common on farm buildings in the area, was vetoed in favour of stone slates. The whole project grew in scale to include a large restaurant, shop, lecture theatre and exhibition space, all set around an open courtyard through which visitors pass on their way down into the landscape park via a gently winding path. The drama of the approach to the centre remains, with a curving approach road passing a Georgian obelisk and the Victorian St Mary’s church, a masterwork of William Burges, and providing a tantalizingly elusive glimpse of the top of the abbey tower.

Credit: Richard Learoyd

Credit: Richard Learoyd

Ted Cullinan once commented that “the English tradition of design isn’t about freedom or even enjoyment – talk about enjoyment and the English will think your work is lightweight, frivolous”. Revisiting my book on the Cullinan practice (published in 1995) and then visiting the visitor centre again (in the midst of lockdown, with the interior out of bounds) I found I had, if anything, undervalued the building –“there are times when the building seems overdone and busy”, etc. For all the irritating ways of the National Trust – a mundane timber hut pitched right by the entrance, for example – it has worn well and seems more than ever supremely appropriate to its setting. There are hints of the Arts and Crafts and of the work of Frank Lloyd Wright (discovered by Cullinan while a postgraduate at Berkeley – where he met Wright). Fountains embodies Ted Cullinan’s progressive, indeed dynamic, vision of tradition as a driver of modern architecture.

Ken Powell is a former consultant director of the C20 Society and an architectural historian and consultant. He is currently completing a book on Edward Cullinan Architects for the Twentieth Century Architects series.

The Building of the Month is edited by Dr Joshua Mardell.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.