This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

Image – Flickr: julesfoto

A 1980’s community mosaic mural on Tottenham’s Broadwater Farm Estate has been Grade II listed following support from C20 Society, saving it from potential demolition and preserving a vital example of London’s under-represented heritage.

A long-planned redevelopment of the estate by Haringey Council had put the future of the mural in doubt, with several residential blocks – including Tangmere House, the location of the artwork – scheduled for demolition. It’s hoped the council will reassess the proposals in light of the listing news.

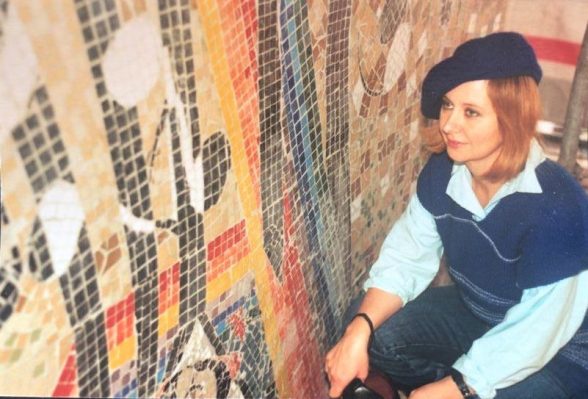

Titled ‘Equality–Harmony’, the mural was created in 1986-7 by artist Gülsün Erbil and was commissioned in the wake of the Broadwater Farm riot in 1985. That year saw riots across London in response to growing tensions between Black communities and the Metropolitan Police. Major riots erupted on 6 October in Tottenham after the death of Cynthia Jarret during a police raid on her home in the Broadwater Farm Estate. This followed riots in Brixton the previous week in response to the shooting of Cherry Groce by police in her home on Normandy Road. The Broadwater Farm riot led to the death of PC Keith Blakelock.

While the mural design was Erbil’s own, the execution was a collaborative process. Erbil – herself an estate resident at the time – established a workshop in an empty commercial unit in Tangmere House, where she taught aspects of the mosaic technique to residents and actively engaged them in the making process.

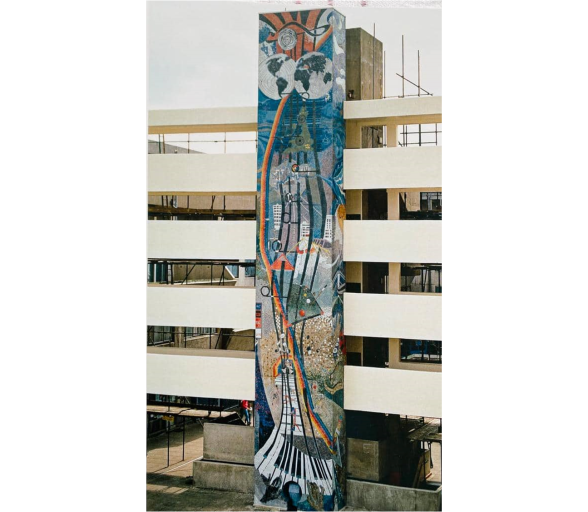

Using a byzantine mosaic style and applied to the exterior face of a five storey concrete refuse chute on the Tangmere House residential block, the imagery of the mural celebrates the universal values of peace, equality, harmony and community, linked by a rainbow and a musical stave running the full height of the work. The motifs narrate a geographic transition from global to local, starting with the two hemispheres at the top of the composition, followed by the map of the UK, the river Thames and London skyline, and finally to the buildings of the estate, its people and the activities they enjoyed.

Image: Gülsün Erbil

The artist Gülsün Erbil commented on the listing news:

‘I started with nothing I ended up being [recognised by] Historic England. I am very very happy and proud. It was a big sacrifice and I was patient enough. ART is a savior and also the doctor is this world. I would like to advice all the young generations to create…All the good messages can come to the world through creations. My message is PEACE & LOVE and EQUALİTY. There is an English saying “If the dreams come true, there are no more dreams” But I believe we can create new dreams…’

Call for further mural listings

The Society also calls for the listing of two other painted murals on the estate: the ‘Peace Mural I’ by Anthony Steele (1987) and ‘Waterfall Mural’ by Bernette Hall and Donald Taylor (1991).

The ‘Peace Mural I’ was commissioned at the same time as the ‘Equality–Harmony’ mosaic and its theme is similar, depicting the busts of three famous advocates for peace: Bob Marley, Mahatma Gandhi and John Lennon. Before them, figures occupy a bucolic landscape, and in the distance there is a mountain with civil rights activist Martin Luther King at its summit. Steele was a resident artist and musician, who had produced the ‘Success Through Caring’ logo of the Broadwater Farm Youth Association. In the documentary Scenes from the Farm (1988), Steele is shown on the scaffold before the mural, on which he claims to have worked for seven to eight weeks. In the clip, the artist addresses the fact that his mural has been vandalized in what was perhaps a racist attack.

The ‘Waterfall Mural’ was completed in 1991 on the Debden block and can be clearly seen when entering the estate from Gloucester Road. Like Erbil’s and Steele’s work, this mural responded to the conflicts of the 1980s. In an interview with Clifford Headley at the Hibiscus Community Centre (2021), artist Bernette Hall explains how the River Moselle runs through ‘The Farm’, “right through the heart of the community” and he reflects on how water is a life-giving force which links people together: “we all drink water”, “we are all part of water”. Water, he continues, also offers a “spiritual cleanse”, it “cleanses what happened”. Hall and Taylor had produced four sketches of different waterscapes and The Farm community had selected the waterfall. In selecting the image, Hall was also inspired by his memories of the sound of rain falling on the roofs of the estate buildings. The mural took seven months to paint and has been described as a symbol of the estate: “what everyone remembers when you say Broadwater Farm” (‘Shocka takes us inside the Broadwater farm estate’, 2021).

Image: Gülsün Erbil

1980s Community mural movement

The ‘community mural movement’—as it has been called by architectural historian Alan Powers—emerged in the late 1960s and reached its zenith in the early 1980s. First popularised in the United States, Joana Zegri’s ‘Evolution Rainbow’ painted in Haight-Ashbury during the ‘Summer of Love’ in 1967 is believed to have been the earliest ‘community mural’ in San Francisco. Similar community murals also began to appear in England around this time, as noted by Carol Kenna of the Greenwich Mural Workshop in a Building Design article, ‘Art and the Community’, of 27 Jan 1984: “In 1967 a group of Black artists in Chicago painted a ‘Wall of Respect’ with local people’s help. At about the same time an English artist, John Upton, painted a mural in south London.” Kenna observes how

‘The motivation for both ventures seems to be similar: a desire by the artists to work in public with all its accompanying responsibility of accountability to different communities and users of public spaces and buildings. Plus, a wish to use their art in ways that were meaningful to members of the general public, and as a commentary on local and national issues.’ There was, she write ‘a firm belief in the latent creative ability in people, and a belief that given the right process, people together with skilled artists can produce artworks that are important to them and also have a real effect upon their lives or their environments.’

Murals produced in the 1970s and 1980s were concerned with community and locality. They were often created by artists in collaboration with residents and sometimes schoolchildren, who were involved throughout the process, in the conception, design and execution of the work. The murals tended to be located on gable ends, garages, stairways and lifts on blocks of flats. They were outdoor public works, existing outside the gallery-focused art world.

There was a surge of new murals in the early 1980s, particularly in London, where many were funded by the Greater London Council (under Ken Livingstone) and local boroughs. Architectural critic and historian Owen Hatherley describes these murals as “the capital’s last surviving remnants of municipal socialism” (Reclaim the Mural, 2013) before the GLC was abolished and local authorities’ resources depleted. These murals tended to depict communities or historic events. Many focused on the struggles of migrant communities and ethnic minorities. Others were anti-corporate, anti-nuclear, and anti-carceral. Perhaps the best known example is Ray Walker’s ‘The Battle of Cable Street’ (1982).

Image – London Mural Preservation Society

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.