This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

Image: Wilkinson Eyre

Catherine Croft | C20 Director

One of the most expensive, ambitious and longest running C20 conservation cases the UK has ever seen is finally crossing the finish line. Battersea Power Station closed in 1983 and is at long last open to the public, and I’ve been along to check it out. C20 Society campaigned for literally decades to keep the sadly decaying building in the public eye, to see off numerous highly destructive proposals for the main structure itself, and curb the size and encroachment of the proposed adjacent development on its magnificent setting. We’ve consistently called for sensitive refurbishment and imaginative reuse, for a solution which works with the grain and character of the building, reinforcing its robust character. We campaigned for interim temporary work to make it wind and watertight, to halt decay and buy more time at stages when many felt that restoration was an unrealistic pipe dream. So is it now a triumph? Should it, or could it, have been different or better? And what can we learn from such a long trajectory for the buildings on our upcoming 2022 Risk List?

Image: James Parsons

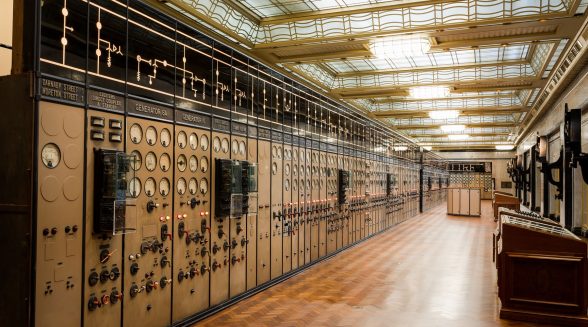

Firstly the positives. Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s Grade II* masterpiece remains a London icon. Both the 1935 Art Deco Turbine Hall A, and the more austere fiancé of the 1950s Turbine Hall B have been restored and are filling with shops. Control Room B will be a cocktail bar, set in amongst the original dials. Working alongside Wilkinson Eyre, Conservation Architects Purcell have over seen “cleaning techniques to reverse the ‘patina of neglect’ present from thirty years of dereliction whilst maintaining the desired ‘patina of age and industry.’ They’ve achieved an excellent balance. The brickwork repairs are exemplary, with handmade replacement bricks sourced from the two firms which made the originals, the overall effect striking a good balance between old and new. Although C20 argued that the case for the reconstruction of the concrete chimneys wasn’t conclusive, the replicas are exact and alleviate all ongoing concerns about maintenance. The space in front of the power station is beautifully spacious with great views of the river, and the new tube link makes it easily accessible.

Image: Wilkinson Eyre

However, how much more we would be celebrating if a more socially beneficial new use for the building itself had been the final outcome, and if the amount of social housing on the site had come anywhere near the levels prescribed for developments in London. The social and cultural success of Tate Modern (Scott’s other London power station, which still remains unlisted) feels like the product of another world, and the comparison takes the edge off Battersea’s success. Battersea is a classy shopping mall, hemmed in by expensive flats which may or may not keep their value. Years of commercial speculation upped the site value and hence the need to maximise profits. Prolonged neglect of the building fabric caused repair costs to soar, and there is still a sense of a better future which might have been.

The lessons for the future must be to look for socially and environmentally sustainable solutions for the restoration of magnificent buildings, and to act fast, to minimise decay and maximise the options for positive conservation.

Image: Wilkinson Eyre

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.

Comments