This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

April 2024 - Dymaxion House, Wichita, Kansas

Image credit: ArchDaily / clublugoesi.es

Dymaxion House, Wichita, Kansas (1944-46)

Buckminster Fuller

By Joe Mathieson

In his 1969 polemic Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, the architect Buckminster Fuller speaks of the utility of fossil fuels in allowing the subsequent production of renewable sources of energy:

…the life regenerating processes must operate exclusively on our vast daily energy income from the powers of wind, tide, water, and the direct Sun radiation energy. The fossil fuel savings account has been put aboard Spaceship Earth for the exclusive function of getting the new machinery built with which to support life and humanity at ever more effective standards of vital physical energy…

The manual’s tone betrays its mid-twentieth century outlook. Its normative framing, its recognisable ‘savings account’, and even the idea of earth as a spaceship urgently in need of a simple guidebook, relates the natural world to the man-made world of the consuming citizen. But beyond the retro-futuristic language, the core concept in the passage speaks to the still ongoing global effort to transition from fossil fuels to renewables. Across his career Fuller stressed the finite status of natural resources and sought to use scientific enquiry to inform his ecologically based design.

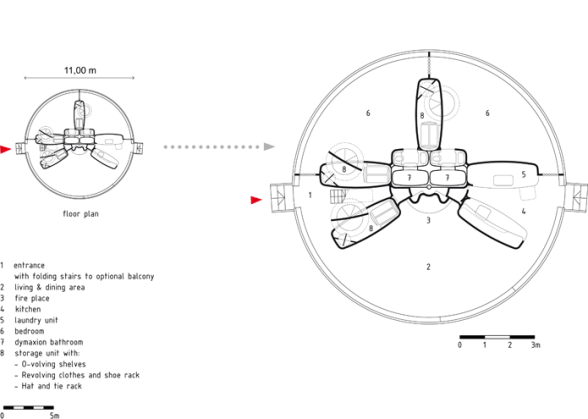

Plan courtesy of Sebastian Kaal

Fuller is today mostly associated with the geodesic dome, a lightweight built structure of triangular glass sheets formed within an aluminium frame. He popularised the domes after experiments on the form with the artist Kenneth Snelson between 1948 and 1949 at Black Mountain College, North Carolina. As with Fuller’s written work, the domes’ somewhat nostalgic aesthetic today can obscure their pressing green ambitions – among them the reduction of building materials and the creative ventilation and heating of space. The geodesic dome received its first major exposure at the 1954 Milan Triennale, with Fuller unveiling a cardboard version that could be assembled with the instructions already printed on. Domes would preoccupy his built work until his death in 1983.

Before geodesic domes became synonymous with his name, Fuller spent many decades developing the ‘dymaxion’. A portmanteau of dynamic, maximum and tension, the dymaxion was a prefabricated residential unit at various points marketed by the Marshall Fields department store in Chicago. Fuller speaks of the typology as attempting to obtain the ‘maximum gain of advantage from minimal energy input’. Across different iterations, dymaxion units were designed as prefabricated off-the-peg systems that could save energy as well as labour. Purchasing a dymaxion was to be relatively easy, with buyers paying it off in instalments – not unlike purchasing a Cadillac.

Image credit: MoMA Collections

Wichita House was among the final prototypes of Fuller’s developed dymaxion system, finishing assembly in 1946 in Wichita, Kansas. It was a mostly freestanding structure of lightweight aluminium, held by the central column which itself contained the utilities and services of the house. Its floor plan was modular, allowing the contraction of the bedrooms to create a larger living room, and vice versa. It was meant to be produced wholesale by the local Beech Aircraft Factory, with a target of 60,000 units a year, but the company decided to terminate the project after the assembly of the first one.

Energy efficiency was baked into the concept of the house, and there was often no clear distinction between this and its simultaneous labour-saving devices. The unit was designed to generate its own power through wind turbines, which in turn also provided a system of natural heating and cooling. Cisterns collected and recycled water. The round shape minimised heat loss and the number of materials needed to fabricate the house. Downdraft ventilation ostensibly drew dust to filters built into the skirting boards, reducing the need to vacuum clean. Revolving and rotating shelves, trademarked as ‘o-volving’, required no bending. The unit was designed to be fire resistant, earthquake proof and able to withstand extreme winds.

It is unclear how many of the technologies of Wichita House did in fact work, and if so, for how long. If the dymaxion houses were machines for living in, they were overdesigned ones, tackling competing issues with no particular focus on any. They are indicative of Fuller’s utopian outlook, which deployed largely untested technological means to solve societal ills with little critique of their origin. The dymaxion system was used to name subsequent inventions of Fuller’s, including the military-based dymaxion deployment unit, the dymaxion car, the dymaxion world map, and his own meticulous diary-cum-scrapbook, the dymaxion ‘chronofile’. It was the organising umbrella for Fuller’s work in the first half of his career, prior to developing the geodesic dome.

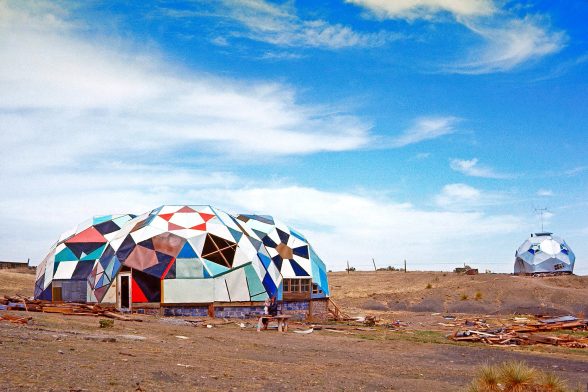

Image by Clark Richert

Fuller’s work on both dymaxion systems and geodesic domes smack of Space Age utopianism, which began to set into American popular culture in the late 1950s, driven by the space programme of successive US governments. By 1959, Fuller’s dome concept had become so advanced that he speculatively proposed the ‘Dome over Manhattan’, a project for a 2-mile geodesic structure over the centre of New York City. The dome would enclose the city and protect it from outside pollution. The project sits in a line of architectural schemes for the city so unrealisable they were hardly ever controversial – such as Ron Herron’s ‘walking city’ concept for Archigram in 1964. But they indicate Fuller’s confidence in the applicability of the geodesic dome on scales small to enormous.

By the mid-1960s Fuller’s thinking and architecture had retained its distinctly techno-optimist bent, but its lack of establishment in mainstream architectural circles had led it, directly or indirectly, to be picked up by American countercultural movements. ‘Drop City’ was one of the first rural hippie communes founded in Colorado in 1965 by filmmaker Gene Bernofsky and his friends. Its early inhabitants based much of their DIY architecture on geodesic domes, fabricating them out of salvaged waste such as car roofs and scrap lumber, citing Fuller as an inspiration. Fuller himself recognised the community by awarding the settlement his first ‘dymaxion award’ in 1966 for ‘poetically economic structural accomplishments’. The community foundered after a few years (potentially apocryphally due to the exposure from Fuller’s recognition), but it led to further ecological work, including inspiring the founders of the Whole Earth Catalog, which ran from 1968 to 1998.

Image credit: Janet Pickel (Flickr)

Wichita House was left derelict for many years after a short operational life, and it was dismantled in 1992. Today it can be found, faithfully reassembled, at the Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation in Michigan. The museum holds many historical curiosities and Wichita House sits comfortably there, as an invention shot through with ambition and, above all, whimsy. But if the house itself didn’t provide the housing panacea Fuller had intended, it was nonetheless the case study that finalised a concept for him. Ultimately it allowed him to move onto later ideas, finesse geodesic domes (now found at the Eden Project among other places), and further influence the intersection of architecture and ecology.

Building of the Month is edited by Joe Mathieson; an Architectural Adviser at the Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust, writer and C20 volunteer.

For pitches, or to discuss ideas for entries, please contact: joe@c20society.org.uk

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.