This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

July 2024 - Hall of Nations and Nehru Pavilion, Delhi

Image credit: © Raj Rewal

Hall of Nations and Nehru Pavilion, Pragati Maidan, Delhi, India

Raj Rewal (1972)

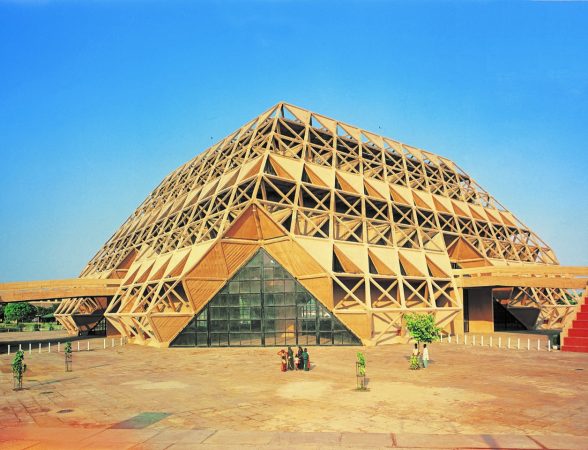

In 1972, architect Raj Rewal – who had trained in Delhi and London and is one of the most distinguished of the second generation of Indian Modernists – completed a vast complex of exhibition pavilions in New Delhi for the international trade fair Asia 72. Making obvious references to the Crystal Palace of 1851, the complex was also intended to mark the 25th anniversary of Indian independence. Inaugurated by Nehru’s daughter, prime minister Indira Gandhi, it was a final architectural symbol of the optimism of Nehru’s post-independence India. However, in 2017, the enormous complex, including a memorial pavilion celebrating Nehru, was demolished overnight despite a vigorous campaign to save it.

Image credit: © Raj Rewal

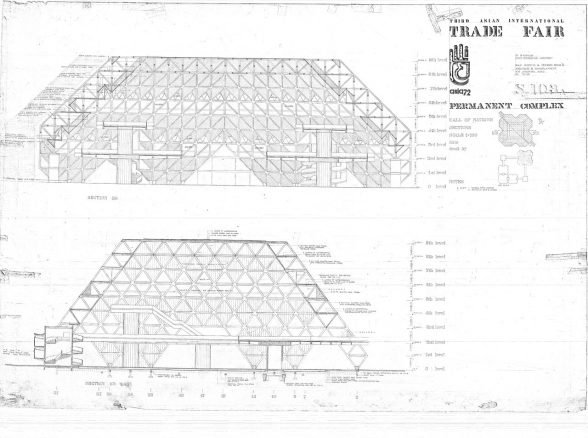

The largest of its four buildings, which resembled truncated Modernist pyramids, was the Hall of Nations. It was the world’s first and largest-span space frame (78m/256ft) to be built in concrete, as steel was too expensive in India at the time. Around 300 families lived on site and built the complex in less than two years; 50 carpenters made the wooden boxes into which the concrete, carried up a bamboo scaffold in baskets, was hand-poured. The entire structure, 16ft deep, served as a 3D brise soleil to screen the sun and cool the building. ‘It was designed as a sunbreaker,’ Rewal told me. ‘Le Corbusier put the sunbreaker on the outside, separate from the structure. Here it is the structure, a three-dimensional jaali [lattice screen], and for many years it did not have glass but was open, so it had the air circulating through it. It did not need air conditioning. Climatically it may be the most important building ever built.’

This innovation was made possible by the Indian engineer Mahendra Raj, who had worked on Le Corbusier’s Chandigarh Capitol Complex as well as Charles Correa’s Hindustan Lever Pavilion (1961), also in Pragati Maidan. The unit of the structure was the octahedron, 5m wide, with nine members meeting at a rhombic reinforced concrete joint. Mahendra Raj’s structural ingenuity enabled some of the striking forms of the modern architecture of post-independence India. With chamfered concrete faces only 25cm thick, the Hall of Nations has a refined yet brutal elegance.

Image credit: © Raj Rewal

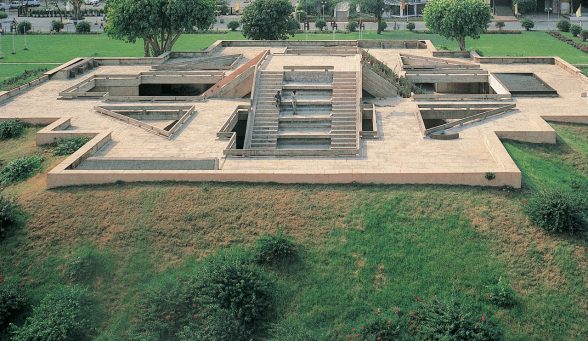

In the same complex, just to the west of this futuristic building, was Rewal’s Nehru Pavilion, an underground gallery that was the negative of the four larger structures. Built to house an exhibition commemorating India’s first prime minister, it had a raised mound inspired by Buddhist stupas, and a geometric plan reminiscent of mandalas, illustrative of the Indian Modernists’ renewed interest in the country’s architectural heritage. Rewal describes it as ‘Modern architecture with Indian roots. We appreciated traditional places in a modern way.’

The biographical exhibition inside the pavilion, Jawaharlal Nehru: His Life and His India, was designed by Charles and Ray Eames in collaboration with the National Institute of Design (NID), the institution that Nehru had helped found. It included portraits of Nehru as a Harrow schoolboy, a reconstruction of the prison cell in Ahmednagar Fort where he was incarcerated for his ninth spell from 1942 to 1945 (and where he wrote The Discovery of India) and large-scale photographs of the Bhakra Nangal Dam and other Modernist structures with which he was associated, including Chandigarh.

Image credit: © Raj Rewal

‘I reread Nehru’s book The Discovery of India (1946),’ Rewal explains, ‘in which Nehru wrote about the difficulties uniting people in India with diverse languages, religions and cultural values. The museum-pavilion enshrined and celebrated Nehru’s ideas, values, and ideals – inclusive growth, democracy, and the upliftment of all sections of society. Nehru was not only a great leader of India but of Asia and the developing world as a whole. He was a visionary with modern concerns. Nehru represented the spirit of new India on the one hand, as well as the austere values of Mahatma Gandhi. He imbibed the ideals of democracy and secular values along with nation-building strategies.’

However, Nehru’s vision of a secular, modern and progressive India is at odds with the trend of much contemporary Indian politics and its more assertive ethos of Hindu nationalism. Like Nehru, Prime Minister Narendra Modi styles himself ‘the Architect of a New India’, but his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) uses architecture to promote a Hindu nationalist rather than secular agenda. Numerous new buildings designed by Modi’s favoured architect Bimal Patel (his Albert Speer, but without the talent, according to artist Anish Kapoor) articulate Modi’s vision of a new, modern Indian cultural identity (of Hindus) united by and able to build on its spiritual past.

Image credit: © Raj Rewal

In 1951 Nehru insisted that the restoration of the Somnath temple in Gujarat be privately funded and that India’s then president should attend its inauguration in a personal rather than official capacity; he chose to invest in his non-sectarian, industrial ‘temples of Modern India’ instead. Modi’s government, by contrast, has financed expensive refurbishments of temples in Varanasi, Ayodhya and Ujjain, and in January 2024 Modi controversially inaugurated a new £170m Hindu temple to the god Ram on the site of the sixteenth-century mosque in Ayodhya that was razed by nationalists in 1992.

A proposal to redevelop Pragati Maidan was unveiled in 2015, a year after Modi’s government came to power. There was outrage across Asia and the world through ARCASIA (Architects Regional Council Asia) and the Union of International Architects, who pleaded with Modi to spare these buildings, as they formed an integral part of India’s modernist architectural heritage. The Indian Institute of Architects went to the courts to fight it, while INTACH (Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage), a semi-government organization, also took legal action to try to preserve it.

Image credit: © Raj Rewal

Image credit: © Ariel Huber

‘They all lost,’ Rewal remembers, ‘and finally I had to hire a lawyer myself – the wife of an architect who was very passionate about it. The judge told her that he would consider the case in four days’ time. But if it had gone to the Supreme Court, things would have been delayed a year, and the government didn’t want that. The very next morning [April 23rd, 2017] they went in with the bulldozers and demolished it’. The model created of the Hall of Nations site as part of Rewal’s legal battle is now in the V&A collection, along with an original design for the Nehru Pavilion (both on display in the Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence exhibition).

Last year, Mahendra Raj’s son, Rohit, took me on a tour of the site, where Rewal’s iconic structure has been replaced by a bland campus designed by a consortium of architecture firms from Delhi and Singapore for the 2023 G20 summit. It was a closely guarded space to which we could not gain access. From the roof of Achyut Kanvinde’s nearby Nehru Science Centre, a brutalist structure with abstracted concrete chhatris that echo those of a nearby Mughal fort, we looked out over a redeveloped Pragati Maidan. A cluster of new corporate buildings in a globalised vernacular surround a circular conference centre that has been cruelly nicknamed ‘The Hamburger’.

Image credit: © PTI File Photo

Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence is on at the V&A until September 22.

Christopher Turner (@TurnerOnDesign) joined the V&A in 2017 as Keeper of Design, Architecture and Digital, and Head of Festivals and Biennales. In 2021 he became Keeper of Art, Architecture, Photography and Design, responsible for over two million objects, from the medieval to contemporary, including eight national collections.

Building of the Month is edited by Joe Mathieson; an Architectural Adviser at the Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust, writer and C20 volunteer.

For pitches, or to discuss ideas for entries, please contact: joe@c20society.org.uk

Image credit: © V&A

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.