This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

August 2024 - Dinorwig Power Station, Wales

Image credit: Cyrille DUPONT / engieUK

Dinorwig Power Station, Wales

James Williamson & Partners, Frederick Gibberd Partnership (1975-84)

Concealed in Elidir Fawr mountain is Dinorwig Power Station, also known as Electric Mountain, its unremarkable entrance giving few clues about the complex within.

The Central Electricity Generating Board (CEGB) – the national body responsible for electricity generation in England and Wales from 1958 until the industry was privatised in the 1990s – oversaw the power station’s development, which was opened by Prince Charles in 1984. This corner of North Wales is home to a cluster of notable twentieth century power stations, including the Ffestiniog hydroelectric power station and the Trawsfynydd nuclear power station, the latter designed by Basil Spence.

Image credit: People’s Collection Wales

In the popular imagination power stations are not sympathetic to their immediate surroundings. They are more often thought of as big and brutish, as unnatural impositions. But rather than being thrust upon the landscape, Dinorwig Power Station was built within it. Still an imposition – and on a colossal scale – but concealed by the mountain face.

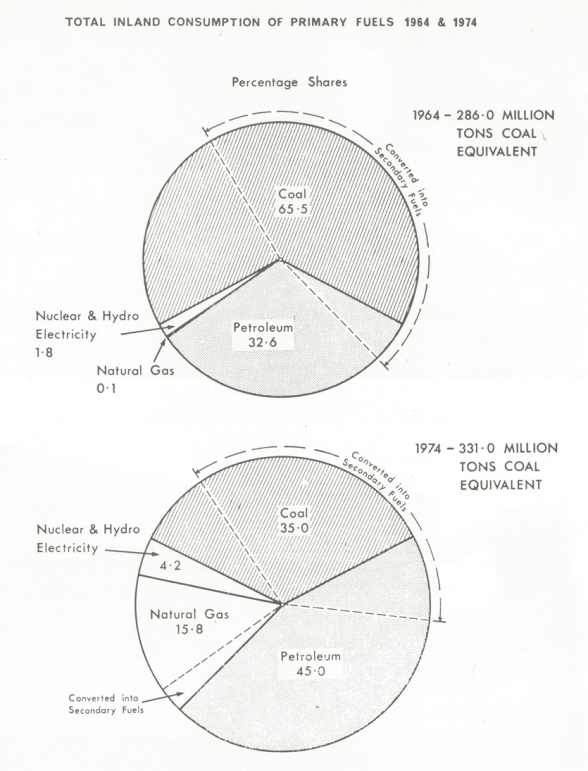

During the twentieth century, there was an increasing need for an infrastructure network that could cope with short-term peaks in energy. Power surges became commonplace, for example the ‘TV pickups’ caused by millions of viewers putting on the kettle during the half time of a big football match or an advert break of a major soap.

Image taken from ‘Coal: Technology for Britain’s Future’ (p24)

Hydroelectric energy can generate electricity much more quickly than other methods of energy generation such as coal, oil and nuclear. It was therefore seen as an efficient and reliable way of responding to these peaks in demand.

The use of hydroelectric power was historically confined to mountainous regions of the UK, such as North Wales and Scotland, due to the combination of elevational changes and natural water sources. The establishment of the National Grid in 1926 increased access to this renewable source of energy to communities beyond those nearby the location of its source.

Image credit: Coflein / RCAHMW

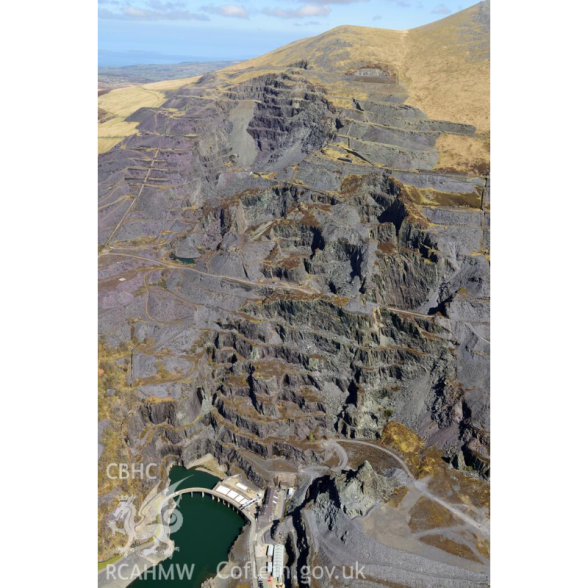

The North Wales Hydro Electric Power Act of 1952 gave powers to the British Electricity Authority, predecessor to the CEGB, to create ‘no fewer than eight major hydro-electricity establishments’, including the Ffestiniog Power Station, commissioned in 1963. The Ffestiniog power station proved successful in balancing the electrical load fluctuation on the National Grid. The CEGB therefore explored the idea of a larger scheme at Dinorwig, a village and former opencast slate quarry on the side of Elidir Fawr mountain.

The location was deemed suitable for several reasons. First, the presence of two natural lakes, Llyn Marchlyn Mawr near the mountain’s summit and Llyn Peris at its foot. Second, the fact that Dinorwig sits outside of the Snowdonia National Park boundary – the entire belt of slate bed areas, of which it is part, were excluded when the park’s boundaries were drawn up in 1947. Third, the area was ‘already deeply scarred by quarry workings’ from the previous two centuries, as described by advocate for the scheme, then-MP Gorowny Roberts. The area already bore the marks of human intervention, the landscape considered less pristine than nearby Snowdonia and therefore suitable for further works.

Image credit: People’s Collection Wales

Even so, 1957 Electricity Act that established the CEGB included a ‘preservation of amenity’ clause, requiring new proposals to consider their impact on the ‘landscape and natural beauty’ of the countryside. The decision was therefore made to completely conceal Dinorwig Power Station within the mountain. As described by Roberts in 1973, ‘Usually in schemes of this kind a principal and proper objection has been to the construction of obtrusive buildings and pylons. In this case the power station and the transmission lines will be entirely underground.’

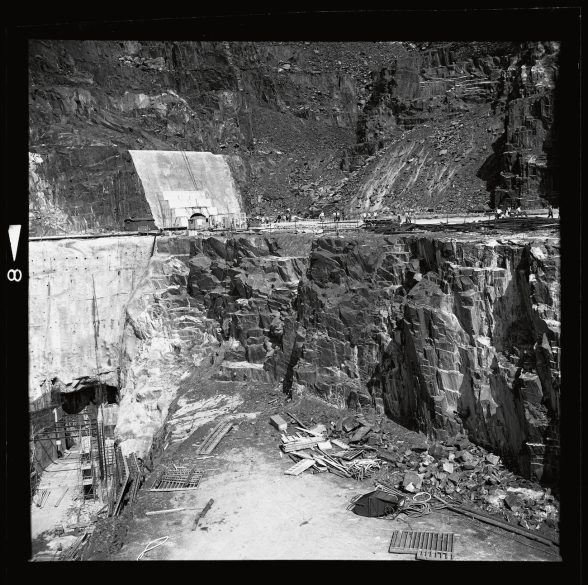

The North Wales Hydro Electric Power Act of 1973 was approved in December 1973 and gave powers to the CEGB to build the hydroelectric pumped-storage station at Dinorwig. The civil engineering contract was awarded to the Alfred McAlpine / Brand / Zschokke consortium and was the largest ever awarded by the UK government at the time.

Image credit: People’s Collection Wales

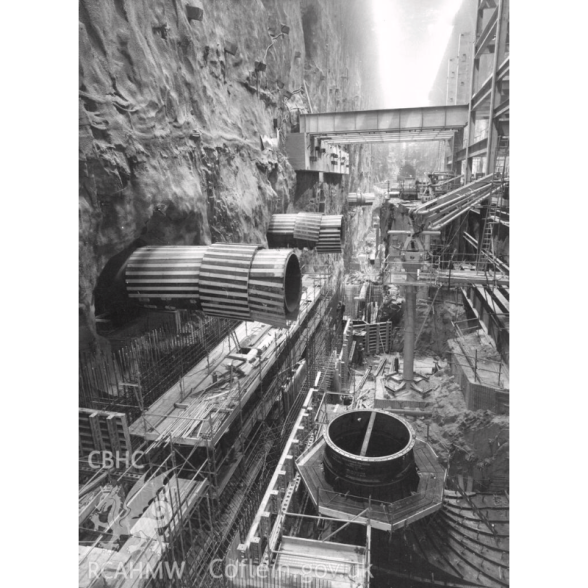

James Williamson & Partners, one of the companies that went on to form Mott MacDonald, was responsible for the design, with works starting in 1975. The construction of Dinorwig involved: the excavation of 12 million tonnes of rock from inside the mountain; the creation of 16 kilometres of underground tunnels; the use of 1 million tonnes of concrete, 200,000 tonnes of cement and 4,500 tonnes of steel; and 2,000 local workers, many of them former slate miners (it was stipulated in the build contracts that a major part of the workforce had to come from the local area). The power station was fully commissioned in 1984. Commonly known as ‘the concert hall’, the main body of the power station is located 750 metres deep inside the mountain.

The two natural lakes at the summit and foot of the mountain act as reservoirs, each lake connected by tunnels. When electricity demand increases, water in Llyn Marchlyn Mawr is released through the tunnels and passed through valves that drive six reversible ‘Francis’ turbines to generate electricity. When there is low electricity demand, surplus electricity drives the same pumps but in reverse, to drive water back up to Marchlyn Mawr reservoir – hence the ‘pumped-storage’ aspect. Through this process Dinorwig can achieve maximum generation in less than sixteen seconds.

Image credit: Coflein / RCAHMW

While the primary intervention was within the mountain, the CEGB did also consider the external landscape. In a period of collaboration between the CEGB and the Institute of Landscape Architects, the 1973 North Wales Hydro Electric Power Act required the appointment of a landscape consultant to advise on the preservation of ‘flora, fauna and the geological or physiographical features of special scientific interest.’

CEGB appointed the Frederick Gibberd Partnership for the Dinorwig project. Their design elements included the burying of outgoing cables for six miles to avoid the need for pylons, the planting of only native tree and shrub species and building the limited number of nearby administration buildings out of local slate. ‘Electric Mountain’ visitor centre in Llanberis formed part of these, which before its closure in 2018 and demolition in 2024 offered minibus tours into the power station complex (I went on one as a giddy child).

Image credit: People’s Collection Wales

Perhaps the most significant focus points of Gibberd’s design were the snaking forms of Llyn Marchlyn Mawr and Llyn Peris reservoirs, sculpted to ‘contour naturally into their surroundings’. The fluid transition between these manmade features and the natural landscape epitomised the view of Sylvia Crowe, then-president of the Landscape Institute and landscape consultant for nearby Trawsfynnd Power Station. Crowe contended that Britain was developing a ‘landscape increasingly punctuated and criss-crossed by power grids and giant new structures’, an idea developed in her 1958 book Landscape of Power.

In 2021 UNESCO designated ‘The Slate Landscape of Northwest Wales’ as a World Heritage Site, on the basis of, amongst other things, its ingenious use of water to sustainably power the quarrying machinery throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. The designation area includes Elidir Fawr mountain and, therefore, the power station within.

Image credit: Gibberd Archive

While not explicitly referenced by UNESCO, Dinorwig Power Station’s use of water for energy generation is equally ingenious, if not more so, and still operates today as one of the largest pumped-storage hydroelectric power stations in Europe. The power station continues to innovate and evolve, now also acting as a sustainable power ‘battery’ for other forms of renewable energy such as wind and solar. The landscape’s heritage status is at odds with this particular mountain, whose contemporary function remains almost completely hidden.

Emma Bennett is a Senior Architect at Archio, occasional writer on architecture and heritage and member of the C20 Youth Steering Group.

Building of the Month is edited by Joe Mathieson; an Architectural Adviser at the Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust, writer and C20 volunteer.

For pitches, or to discuss ideas for entries, please contact: joe@c20society.org.uk

Image credit: Cyrille DUPONT / engieUK

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.