This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

Image credit: Simon Carder

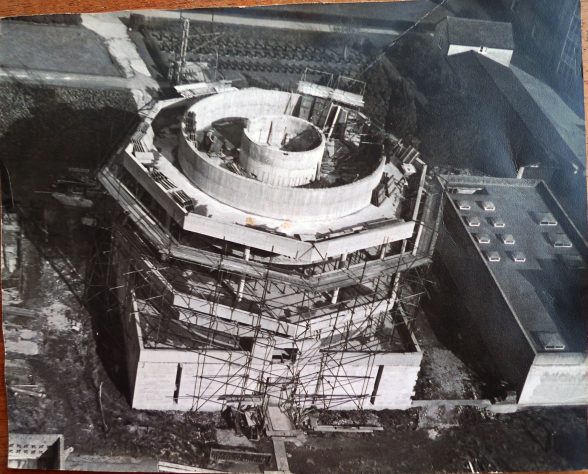

The Library (1965-70) and East (or Pollen) Wing (1970-75) at Downside Abbey in Somerset have been listed at Grade II and II* respectively, following an application by C20 Society. Designed by Francis Pollen of Brett & Pollen architects, the buildings combine references to Edwin Lutyens in limestone ashlar and bush hammered concrete, with the spectacular geometric volumes of the glazed octagonal reading room.

The recent departure of the last monks from Downside leaves the monastic buildings without a function, and the Downside Abbey General Trust is in the process of creating a future strategy for the site. The Society is pleased that these new designations will allow the Abbey’s 20th century heritage to be properly considered in any potential plans for Downside.

Image credit: Alan Powers

Downside Abbey Library

While technically by Brett & Pollen, Downside Abbey was primarily the work of Francis Pollen. Built in 1965-70, Downside was produced around the same time as his masterpiece – the Abbey Church of Our Lady Help of Christians, at Worth Abbey. These were key years in Pollen’s career which saw his mature style develop. Downside was therefore an important project within Pollen’s oeuvre.

The library is a five-storey, modernist structure, located on the east side of the Downside Abbey site. Though it stands as an independent structure, it is connected to the Abbey via an elevated walkway that attaches to the east wing of the monastery. It was built in accordance with a desire to open up the Abbey to the outside world and to make it a centre for scholarship. The ground floor podium is a quadrilateral volume with ashlar facing and is square in plan. On top of it sits a shallow ring of dark brick supporting an octagonal volume containing the offices, catalogue room and lecture room. The next two storeys comprise the main octagonal element of the Reading Room. This is surmounted by the circular special collections room, which is then topped by a triangular structure containing the lift pulleys. The circular, special collections storey has a continuous, windowless façade along its exterior circumference. It is composed of bush-hammered concrete and has been set far back into the body of the structure, matching the level of the mezzanine floor in the octagonal Reading Room below.

The main design challenge faced by the new library was fitting within a site that was bounded by the cemetery, church, east wing and kitchens, without both overshadowing the future east wing while being physically connected to it. The building was designed to be as compact as possible, and though each floor is based on a different geometry, the entire structure was designed to fit within an imaginary 60-foot cube. The result of these careful geometric volumes reduces the visual mass of the building while bringing it into scale with the C19 church to the north.

The podium was designed to be deliberately windowless, mitigating any damage daylight could cause to the books within. Only a few narrow slits permit light to enter this volume, exclusively for the internal study carrels. Its four ashlar facades have uneven coursing that emphasises its horizontal lines. As typical of Pollen’s designs, these walls have been battered inwards, affording them a sense of strength under compression. As would later be seen in the design for Worth Abbey, Pollen’s design was an inverted version of the centralised plan, creating a structure that was ‘uncompromisingly modern’ (Alan Powers, Francis Pollen, p. 95). Pollen described the completed library design as a ‘synthesis of the conditions and restrictions imposed by the site’ and overcoming the visual problem of designing a modern building in such close proximity to a Neo-Gothic church (Francis Pollen, ‘the new monastery library’). Alan Powers has stated that “it [the library] is like a chapter house in a cloister, an ‘object building’ deliberately contrasting with its neighbours. As such, I think it contributes to the group in a very strong way. The angled finials […] give it a sense of directionality – pointing to the crossing tower of the abbey church”

Image credit: Lynch Architects

East Wing

When the Downside library was completed, the building team turned their attention to a new monks’ refectory, with a school refectory below, and guest rooms above. This structure would replace an existing temporary building known as the White House, which had been constructed over the unfinished Weld Cloister to the east of the Downside Abbey site. Its east and west elevations are composed of narrow coursed rusticated stone, contrasted with bands of board-marked concrete in the style of Le Corbusier’s Maisons Jaoul. The wing originally contained three storeys, with a fourth added later and dressed in ashlar stone.

Pollen’s wing is largely horizontal in comparison to the previously vertical interventions of Leonard Stokes on the Downside Abbey site, but the east wing is characterised externally by the repetition of triangular, V-shaped window bays that extend along the entire east and west facades. These bays correspond internally to the guest rooms, and the provision of a window on both sides of the bay allows for either window to be opened depending on the direction of the wind. Alan Powers argues the effect of these bays would be ‘restless’ (Alan Powers, Francis Pollen, p. 96), but given the elaborate Gothic detailing of the surrounding C19 structures, they correspond to the architectural complexity of the site. The topography of the land falls steeply, with the level of the cloister on the west side of the site being level with the upper storey of the new east wing. Rather than attempting to conceal the irregularity of the site, Pollen emphasised it through the exaggerated projection of the reinforced concrete brackets that support the triangular window bays.

The wing is entered from an upper level and provides a point of public access to the monastery complex. The fall in the topography forms a low passageway inside the building through the basement, and the main corridor is lit by arch-headed windows. School pupils utilising the east wing pass along the lower corridor that corresponds to the footprint of the former Weld cloister, before ascending a grand staircase as they enter the church. The stairwell is top-lit, creating unique light effects against the flush-pointed brickwork of the internal walls. The refectory ceiling is composed of polished hardwood with ribs, which has been angled downwards to the centre and folded to correspond to the angles of the window heads. The concrete lintels that support the ceiling are expressed externally through the exaggerated concrete brackets upholding the window bays.

Once both the library and east wing were complete, the elevated walkway between both structures was built, featuring rusticated stone piers and reinforced concrete facing over the main walkway element.

Image credit: Alan Powers

Future of Downside

Downside school and monastery have separated in the wake of the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA). The Benedictine community have now left Downside, their home for over 200 years, for Buckfast Abbey in Devon. No plans are currently in place for the community’s buildings in the north of the site, which are held by the Downside Abbey General Trust. The school, a separate entity, will continue to operate in the buildings to the south.

Numerous architects have been involved in the development of Downside Abbey since the 19th century. The Grade I listed Abbey Church of St Gregory the Great was built in phases between 1872 and 1938, involving Archibald Matthias Dunn, Edward Joseph Hansom, Thomas Garner, Frederick Walters and Sir Giles Gilbert Scott. The Grade II* listed monastery and cloister ranges, which adjoin onto the western end of the Abbey Church, were built in 1873-99 by Archibald Matthias Dunn and Edward Joseph Hansom, and the School—the Old House, old chapel, school, main refectory and associated buildings of which are Grade II*—involved Henry Edmund Goodridge, Charles Hansom, Dunn, Edward Joseph Hansom, Leonard Stokes and Gilbert Scott.

Most of the buildings on the site were already nationally listed in the 1960s and 70s and their listings amended in 1989, at which point the library and east wing would have been considered too young for consideration. The recent sale of this part of the Abbey site left these buildings vulnerable to change or development, so the Society is pleased that the new designations will allow them to be properly considered in any future strategy for Downside.

Image credit: Downside Abbey

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.