This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

Image credit: C20 Society

They brought European architectural modernism to working class communities across the country, and delivered widespread health and welfare benefits some two decades before the founding of the NHS, yet the story of Britain’s pioneering Pithead Baths has been almost completely forgotten. Now a new research project, led by C20 Society and Queen’s University Belfast, aims to shed new light on their legacy and discover exactly how many of these ground-breaking buildings remain.

Funded by the Mellon Foundation and the Arts and Humanities Research Council, with support from the national mining museums of England, Scotland and Wales, research by ‘Miners’ Modernism: Pithead Baths – Past, Present and Future’ has so far identified 65 surviving examples across the former coalfields. The project is now calling on local heritage groups, ex-miners, and mapping sleuths to record further examples and help complete the picture.

A one-day symposium in London this Autumn presented interim findings from the project and brought together experts from Germany, Poland and the Netherlands to discuss innovative approaches to mining heritage across Europe. Legendary banner-maker Ed Hall – a regular collaborator of artist Jeremy Deller, who won the Turner Prize for his recreation of the 1984 Battle of Orgreave – was commissioned to design a striking trade union style backdrop for the occasion (pictured), which its hoped will now go into the permanent collection of the National Mining Museum.

.

Do you know of a surviving Pithead Bath building in your area, or of local heritage and interest groups that may do? Explore the database via the C20 website and submit an update to help contribute to the project.

Click here: C20society.org.uk/pithead-baths

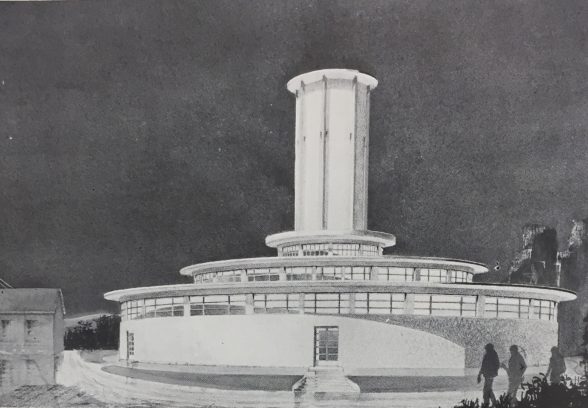

Described in 1938 by critic and broadcaster Anthony Bertram as “a colossal social experiment taking architectural form”, Pithead Baths allowed coal miners to wash at work before returning home, serving in excess of half a million workers on a daily basis. Mandated by the Miners’ Welfare Committee, designed by their in-house architects, and funded by state-legislated levies on coal production and profits, this was an unprecedented progressive building programme, which acted as a powerful propaganda tool for the wider coal mining industry.

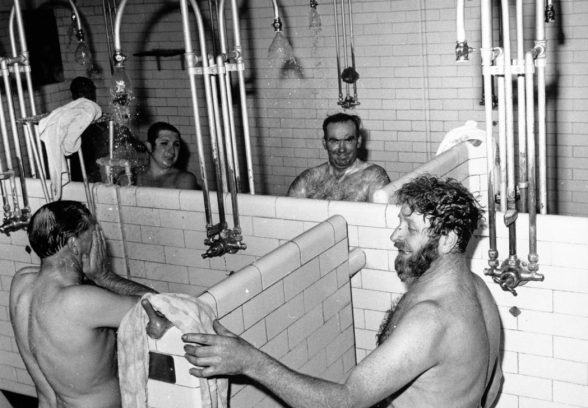

The light-filled, communal, clean, and spacious Pithead Bath buildings were in complete contrast with the often bleak and isolated environments associated with the country’s coalfields. As well as providing heated showers for the first time, they also included facilities for dirty clothes to be dried and stored, in specially designed heated and ventilated lockers. The separation of industrial dirt from the domestic environment had a transformational effect on workers and their families. Previously miners would have had to bathe at home, usually in a tin bucket, with the presence of coal dust being linked to elevated rates of infant mortality.

The design and look of the buildings were also of great importance, drawing inspiration from the Dutch modernist architecture of Willem Marinus Dudok; in particular the schools and civic buildings he designed during the 1920s and 30s in the town of Hilversum, near Amsterdam. They combined strong horizonal and vertical elements – a tower to store the water, with a long, low block for the showers and changing areas. Distinctive features of the early modern movement were commonplace in Pithead Baths, from steel framed streamlined windows, to projecting concrete canopies, and pale-coloured engineered brickwork.

They were deliberately designed to be not only the best buildings within the colliery, but in the whole community. The socialist campaigner Katharine Glasier describing them as ‘white shining Temples of Health’, where ‘a spiritual bath is in fact part of their function’ (Bertram).

Between the 1920s and 50s, approximately 800 Pithead Baths were constructed at collieries stretching from Kent to the Scottish Highlands. Following the collapse of the coal mining industry in the later years of the 20th century, most colliery sites were comprehensively redeveloped and relandscaped, leaving almost no trace of the bath buildings. This physical absence has been echoed in architectural history: while the modernist legacy of the London Underground stations in the 1930s and 40s remains much celebrated, the immense social contribution of Pithead Baths has been almost completely overlooked.

A new map and database on the C20 Society website has plotted the approximate location of every colliery that had constructed a pithead bath building up until 1940, using data found in the National Archives. Researchers have so far identified 65 examples of Pithead Baths that still survive in various conditions – around 8% of the total number built.

Some are in ruins, many have been repurposed for agricultural or light industrial usage, as workshops, offices, MOT garages, salvage centres, or storing farm equipment. A handful are in use as caffs, community halls and scout huts, and one extraordinary example in the Scottish borders has been converted to a private home, with a design inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright. Just a handful of the surviving Pithead Baths are protected by national listing – 3 sites in England and 5 in Wales, with none in Scotland.

Perhaps the most significant of these is Chatterley Whitfield, in Staffordshire, listed at Grade II* and part of the most complete example of a large-scale colliery in the UK. Opened in 1937, it was once the second largest baths complex in the country, and after the colliery closed in 1977 it became a mining museum until this closed due to financial difficulties in 1993. Unused ever since, the building is now in a perilous condition, and is on the Historic England Heritage At Risk Register for being at ‘Immediate risk of further rapid deterioration or loss of fabric’. An extensive feasibility study by Stoke-on-Trent City Council and Historic England in 2022 demonstrated the potential to regenerate the site as a centre for geothermal energy technology research, as well as education, heritage, homes and food production, but the multi-million pound funding required has yet to materialise.

Image credit: Tom Robinson (https://ravenwing93.co.uk)

From former miner Henry McDonald, of the pithead baths at Chatterley Whitfield:

“The ‘Miners Playground’ – That is what I called pithead baths, never a dull moment in them. As we know, many pits in the olden days didn’t have them so it was straight home, tin bath out in front of the fire. I’m talking now about a colliery I worked at in the 60’s. It had got the most up to date baths in the country, constructed in 1936-37 and opened in 1938 with 3,817 clean lockers and 3.817 dirty lockers.

The tricks miners got up to in the showers. Like flipping their towels when you passed by, on your backside (It stung). Best trick was to leave a blank television screen on your mates back where you hadn’t washed. Nobody would tell him and he would get a telling off when his Mrs saw it when he went. Another trick was with fairy liquid (used for Washing up) which miners used instead of using soap. So when washing their hair another miner would stand behind him, pouring the fairy liquid on making more suds. They would be there for ages.

After all that tom foolery it was the comradery amongst all the miners, which was first class. Even those that didn’t join in they had a laugh at the tricks miners got up to. To this day I have to smile about it, I was one of the ‘lads’.

It meant the world to me, been able to get a good shower after a hard day’s work underground in the mine and not travelling home in your dirty clothes.”

Comments

Coco Whittaker, Head of Casework, C20 Society:

“We are delighted with the findings of the project so far, which has included the discovery of 65 surviving Pithead Baths across the UK. Are there more out there yet to be found? Almost certainly, but for this we need your help! We’d invite budding historians, ex-miners, and anyone living in the former coalfields to the browse our interactive map, share it with friends and family, and submit any updates via our website.”

Oli Marshall, Campaigns Director, C20 Society:

“Industrial heritage is particularly vulnerable to obsolescence and demolition, and the pioneering Pithead Bath programme is an unheralded chapter of our social history that is quietly slipping away. The stark fact is, there are likely to be more Neolithic henges in Britain (circa 100) than surviving Pithead Bath buildings. As the country marks the end of coal, its timely to acknowledge how pivotal these largely forgotten buildings were in the development of modern Britain.”

Professor Gary A. Boyd, Queen’s University Belfast:

“Highly significant yet mostly overlooked, the few architectural remnants of Pithead Baths left provide a potent memory of radical and enlightened social policies that transformed hundreds of thousands of lives”.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.