This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

September 2025 - Chapel of Reconciliation, Berlin

Image credit: Ansgar Koreng / CC BY 3.0 (DE)

Chapel of Reconciliation, Berlin

Reitermann and Sassenroth, 2000

No other city treats memory so architecturally as Berlin. As the unofficial capital of memorials, its monuments confront the city’s — and some of humanity’s — deepest wounds with concrete, glass, steel and stone. But unlike the intentional starkness and heft of other sites in the city — notably the Monument to the Murdered Jews of Europe, the Jewish Museum and the Topography of Terror — there is one structure that slips almost unnoticed into its surroundings: the Chapel of Reconciliation (Kapelle der Versöhnung).

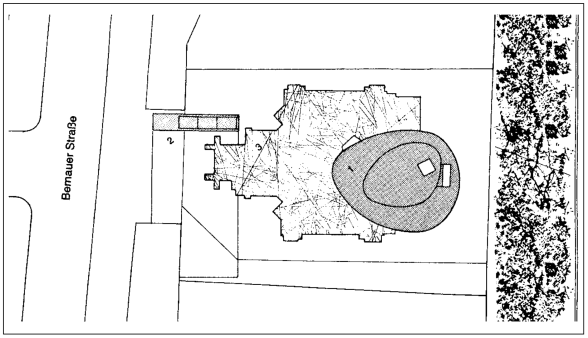

Set within the Berlin Wall Memorial on Bernauer Strasse, the chapel is easy to miss. The 1.4-kilometre memorial site, created in 1998, commemorates the partition of the city with a large open-air exhibition that includes the Berlin Wall Documentation Centre, a 60-metre section of the original border wall and a visitor center. Amid these pieces of historical narrative, the chapel recedes quietly into its surroundings. Set back from the street and tucked between rows of trees and residential blocks, its subtle presence is more retreat than monument.

The chapel stands on the site of its predecessor, the 19th-century neo-Gothic Church of Reconciliation, which had the misfortune of landing squarely in the Berlin Wall’s ‘death strip’ — a no-man’s land between East and West where, from 1961 until 1989, access was impossible. Cut off from its parish and left to decay, the church was eventually demolished by the East German government in 1985. After Germany’s reunification in 1990, the local parish chose not to rebuild the church in its former image, but instead commissioned something new — a structure that reconciles past and present, presence and absence, the earthly and the eternal.

Designed by Berlin architects Rudolf Reitermann and Peter Sassenroth, and completed in 2000, the new chapel is at once modest and radical. Its materials are humble, its scale intimate. But its spatial and symbolic logic is deeply intentional, heeding to architectural historian Antoine Picon’s warning that ‘it is a dangerous temptation for architecture to believe that it has the key to ending conflict rather than revealing its true nature.’ The chapel does not attempt resolution through form. It allows space for truth.

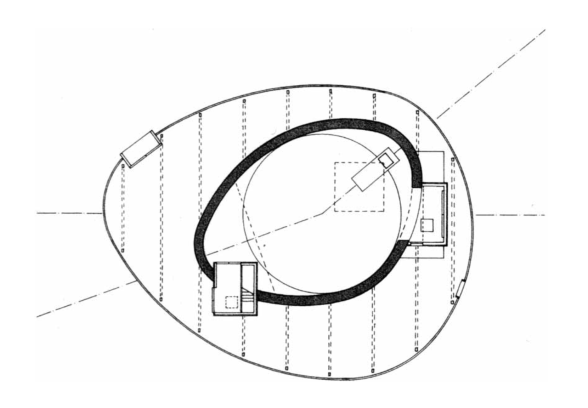

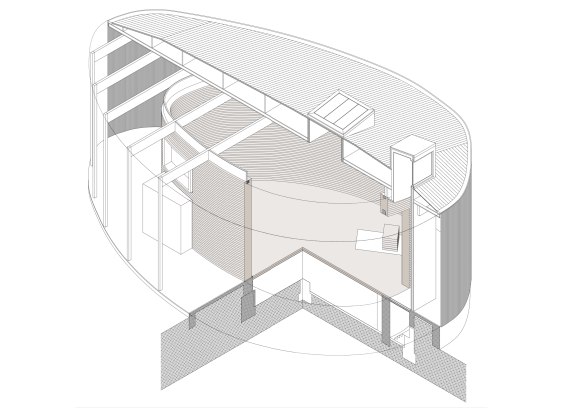

The chapel’s plan is deceptively simple: an outer shell of vertical timber slats surrounds an inner oval wall of thick rammed earth. The wood slats, spaced about six inches apart, float around the chapel like scaffolding, neither fully enclosing it nor fully exposing the interior interstitial space behind it. Made of untreated Canadian Douglas fir, they have gradually weathered with a silvery patina. Above the entrance, a section of these slats is stained a darker gray to create the image of a cross – the only visible indication from the outside of what this building might be.

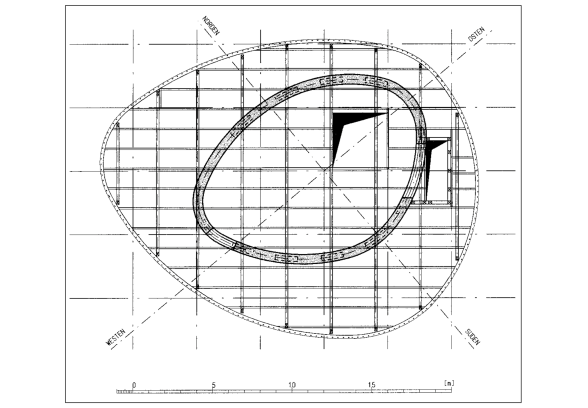

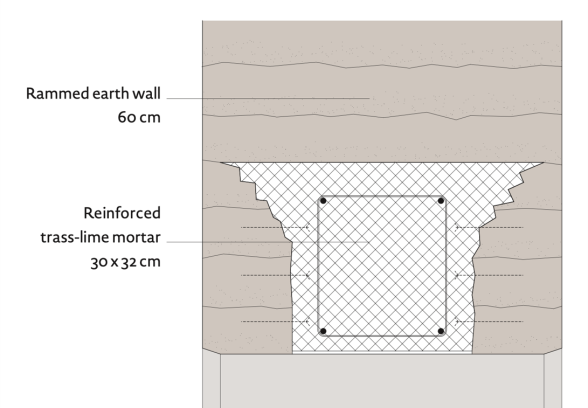

The inner rammed-earth wall is the chapel’s most notable architectural feature — and its greatest engineering feat. Designed by Austrian builder Martin Rauch, a global pioneer in contemporary rammed-earth construction, the seven-metre-high, half-metre thick wall was compacted by hand, layer by layer, with the help from a charity that specialises in the preservation of historical monuments, along with volunteers from fourteen countries. Made from a 400-ton blend of clay, straw fibres, crushed brick and other salvaged material, the wall is both structure and symbol, visibly formed by human effort. The in situ rammed-earth structure also performs thermally: without mechanical heating or cooling, the interior space is passively conditioned through its thermal mass. In addition, rammed earth forms not just the enclosing wall of the inner sanctuary, but also the floor and altar table, grounding the liturgical space in the literal soil of the site. It also serves a structural role, supporting a series of laminated timber beams that span the inner space and cantilever outward, creating an interstitial ambulatory — a kind of liminal corridor — between the chapel’s core and its exterior skin, allowing visitors to wander this passageway freely.

As the first public building in Germany in over 150 years to use load-bearing rammed-earth walls, local authorities faced an unfamiliar challenge. With no existing regulations or building codes to help guide the construction process, legal and technical improvisations were necessary, including its own tailored permit approval process and guidance from structural engineers at the University of Berlin. Months of rigorous and costly testing followed, resulting in a required safety factor seven times higher than standard. The building was as much a precedent as a structure.

Today’s chapel not only bears the name of its predecessor, but also its remnants. Preserved fragments of the earlier church — flecks of ceramic tile, shards of glass, even charred wood — have been quietly reinstated and visibly embedded in the textured walls, forming a tangible sedimentation of memory. Other artefacts recovered from the demolished church remain visible in the sanctuary as well. The most prominent is its original cross, placed in an alcove cut out of the rammed-earth wall. A broken remnant of the former sandstone altar, discovered during excavations, lies embedded in the floor. The old reredos — a heavily damaged relief of the Last Supper salvaged from the demolition — hangs again behind the altar, in the place it once occupied.

Image credit: Mark Bessoudo

Terms like ‘recycled’, reclaimed’, ‘upcycled’ — or the more fashionable ‘circular’ — might suffice in describing the designers’ material reuse strategy, but they are too clinical, too hollow to capture its essence. This building is not merely assembled from the remnants of the past; as its final form makes clear, the whole is more than the sum of its parts. Here, sustainability, like memory, is no gimmick or slogan, and it is not incidental to the structure: it is the structure.

The chapel’s organic and fragile materials contribute to the synaesthetic experience of the space. ‘Architecture is the art of reconciliation between ourselves and the world,’ the Finnish architect and theorist Juhani Pallasmaa once observed, ‘and this mediation takes place through the senses.’ The chapel enacts this principle through both material and light. The absence of windows severs the room from its urban context; daylight is instead quietly drawn into the chamber from a skylight above. This upward reorientation redirects the visitor’s gaze from the horizontal to vertical, in a symbolic disruption of the city’s historical East-West divisions.

Image credit: Florian Monheim

This chapel is best understood in apophatic terms: its architecture speaks most powerfully through absence, defined not by what it displays, but by what it deliberately withholds. There are no windows to offer orientation, no stained glass to mediate light, no air conditioning systems to regulate comfort, no furnishings that command reverence. While it lacks ornamentation in the traditional sense, its austerity is not an aesthetic choice alone, but a refusal to be overtly symbolic.

Outside, the open space surrounding the chapel is sown with rye every year. For a site along the former Wall’s ‘death strip’, this marks the return of life and of the transformation of this place. (Seeds harvested from here were used to sow an additional twelve fields of rye across Europe, from the Baltic to Bulgaria, each at a site commemorating a painful period in their history.)

Image credit: Thomas Jeutner

This sense of living memory is sustained through ritual as well as form. The chapel was officially consecrated on 9 November 2000, the 11th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. Each year on this date, and on the anniversary of the Wall’s construction (13 August), the chapel becomes a site of public memory, hosting memorial services and commemorative events attended by representatives of the Berlin Senate and House of Representatives, members of the Federal Government and other international delegates, as well as relatives of the victims, local authorities and representatives of various religious denominations.

Though its architecture may be modest, the Chapel of Reconciliation carries its name well. It is a reflection of the communitarian design and construction process and a desire to create a place of memory and hope, in which visitors — believer and non-believer alike — could encounter reconciliation. As the architect and theologian Bert Daelemans remarked in the book Spiritus Loci, the Chapel of Reconciliation ‘is a wonderful example of contemporary church architecture, of which humanity may be proud.’

Mark Bessoudo, MCABE – Mark is an interdisciplinary writer, researcher and Chartered Building Engineer. He is currently completing an MA in Architectural History at the Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London.

You can find Mark on Instagram (@markbessoudo) and Linkedin

Image credit: Mark Bessoudo

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.