This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

October 2006 - The Mersey Tunnel

Engineers: Sir Basil Mott and JA Brodie, architect: Herbert J Rowse

Text by Eddy Rhead

Whilst great credit for the design of the tunnel that links Liverpool and the Wirral should go to the engineers, the honour for final detailing and the aboveground ancillary buildings goes to Liverpool’s most eminent inter war architect, Herbert J Rowse. In the interwar period Rowse progressed stylistically from the classicism of India Buildings (1923-30), and Martin’s Bank (1927-32), through to the Dudok-inspired Philharmonic Hall (1936- 39), via a more streamlined Art Deco feel to his buildings for the Mersey Tunnel.

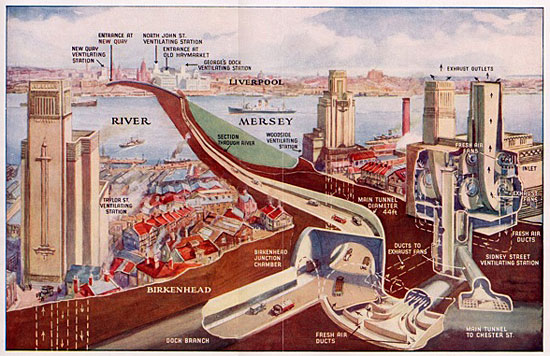

The need for a tunnel arose when the Mersey Ferry became over-burdened in the early 1920s, with over 35 million passengers using it annually. A railway tunnel had already been built in 1886, but the undertaking of a road tunnel would be an ambitious one and, at the time, the largest underwater tunnel in the world.

The engineering endeavours underground were to be matched by the building, above ground, of the huge structures to house the equipment needed to ventilate the tunnel. As well as the ventilation buildings, Rowse designed the tunnel entrances with their associated structures and the tunnel lining, which had a dark purple Vitrolite dado framed in stainless steel, an exotic detail in a dark tunnel not immediately noticeable from a moving car.

Charles Reilly had complained that the tunnel’s entrance on the Liverpool side was in the wrong place in relation to the St George’s Hall, and he felt Rowse had been presented with an impossible task, stating that:

“The engineer too often feels he can cover his mistakes by calling in an architect to add pretty things to hide them.”

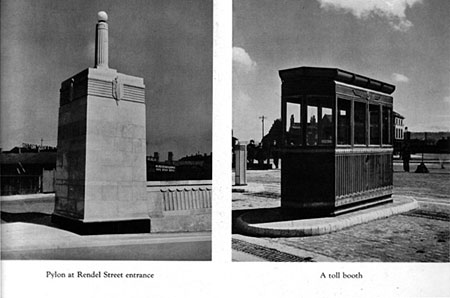

The ‘pretty things’ Rowse added were toll lodges, a now sadly removed lighting pylon, along with an elegantly arched tunnel entrance in Portland stone, headed by a relief of two bulls ‘symbolic of swift and heavy traffic’ with other carved decoration by Edmund Thompson and George Capstick. The grand structural gestures and decorative touches continue at the grandly named George’s Dock Ventilation and Control Station at the Pier Head, proportioned to fit the huge fans needed to extract foul air from the tunnel and force clean air in. Rowse, in the face of the decoration-stripping young architects of the Modern Movement, chose to add many fine decorative touches to this essentially utilitarian building. The building is faced in Portland stone. On the west side is a figure, once again by Thompson and Capstick, wearing helmet and goggles, representing Speed. The black basalt figures of Night and Day suggest a tunnel always open and four panels on the north and south sides show Civil Engineering, Construction, Architecture and Decoration.

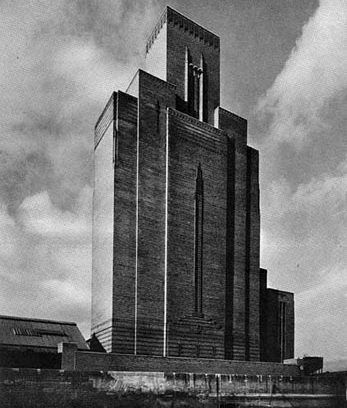

Across the water, on the Wirral side, the main entrance shared many of the same motifs and small-scale structures as the Liverpool side. Major road reconfiguration has seen the loss of the original layout but the twin to the removed Liverpool lighting pylon remains. Rowse dispensed with the fine Portland stone and fanciful decoration for the ventilation shafts on this side of the Mersey, but their scale and situation compensate. The Woodside Ventilation sits hard to the bank of the river and is built in brick and simply detailed. Its massing and form make for a striking landmark, unmistakable when viewed from the Liverpool side and awe inspiring when seen at close quarters on the Birkenhead side.

Despite their mundane and utilitarian purpose the structures designed by Herbert Rowse for the Mersey Tunnel are beautifully detailed and add a unique set of buildings to Liverpool’s rich architectural heritage.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.