This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

February 2014 - University of Ibadan, Nigeria

by Tim Livsey

The University of Ibadan’s buildings present an interpretative labyrinth – but that’s what makes them so interesting. Planned and built between 1948 and 1958 to house Nigeria’s first university, the campus offers a spectacular display of Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew’s brand of ‘tropical modern’ architecture. Their designs for the university, virtually a city in its own right, included halls of residence, lecture theatres, places of worship, and a dramatic library.

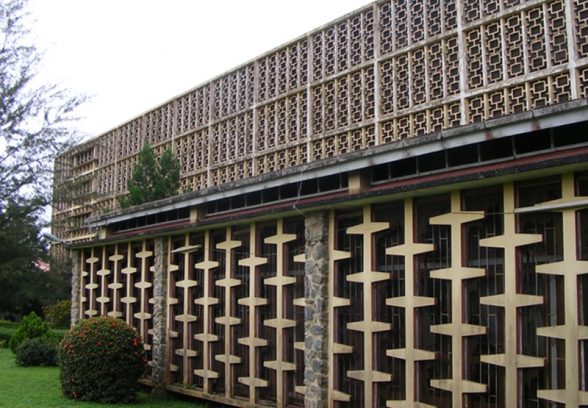

Fry and Drew designed for the Festival of Britain whilst working on the university, and the sunny optimism of the Festival also shone on plans for Ibadan. The university central hall took the form of a miniature Royal Festival Hall, while hall of residence 1’s wavy dining room roof was a reprise of Fry and Drew’s distinctively-roofed Festival cafeteria. (They had also designed a wavy-roofed university chapel, but the plans were abandoned after an unfavourable reception from the Christian Council of Nigeria.) Their later, mid-fifties designs were at once more futuristic and more organic. The concrete domes of the mosque and fourth hall of residence are striking pieces of engineering that introduced curves onto the campus. The library forms its centre, lying alongside the sports fields like a ship at anchor, its vast bulk enclosed by moulded concrete screens designed to refresh readers with a soothing cross-breeze.

Despite Fry and Drew’s assiduous planning for the southern Nigerian climate, there is an odd Englishness about this Nigerian university. The halls of residence are planned around intimate quadrangles, a reinterpretation of old Oxbridge colleges in pale concrete, with neat lawns, porters’ lodges, and halls for formal dining with a raised ‘high table’ for status-conscious lecturers. The jarring juxtaposition between the Englishness of these buildings and their Nigerian site reminds us that their meaning was formed as much by decolonisation politics as it was by their architecture.

For the British, the university buildings symbolised their benevolent brand of post-war colonialism, which was to lead Nigeria in a single bound into the modern world. Many British observers were struck by the contrast between Fry and Drew’s pristine modern buildings and their African site, seeing the buildings as an emblem of a modernity that would soon embrace the whole of Nigeria. In 1955, a writer for the respected medical journal The Lancet contrasted the ‘striking modern buildings’ at Ibadan with their perception that Nigeria was ‘for the most part, very primitive’.

Many Nigerians hoped that the university offered a foretaste of widespread national development. The chiefs of Ibadan helped to secure land for the university, having been advised by local businessman Akinpelu Obisesan that it was for ‘the purpose + of training of their own children, so that they may become sharers from its benefits.’ The very foreignness of the buildings seemed to offer evidence that Nigerians were at last being offered the first rate education that colonial rule had so often denied them. ‘Only such buildings befit a great nation’, wrote Chuma Ajaegbu-Mgbakor, a Lagos businessman, in the Daily Times.

For others, the buildings symbolised a plot to educate a new Nigerian elite more sympathetic to British interests than those of their fellow Nigerians. For the celebrated playwright Wole Soyinka, a former Ibadan student, the ‘scrupulously geometric’ buildings represented the university’s isolation from its African environment. Nationalist leaders attacked the buildings’ fabulous expense, Nnamdi Azikiwe telling the House of Representatives in 1954 that they were symptomatic of ‘sqandermania’. ‘What this country sorely needs today is a first-class institution of learning and not a first-class collection of stream-lined buildings’, insisted Azikiwe.

In recent years, scholars have tended to agree that Fry and Drew’s buildings, however well-intentioned, represented a British vision of African progress that proved of limited use to most Nigerians. The buildings were ferociously costly, and used by only a tiny group of elite students. The world they created of cosy quadrangles, lavish dining and recondite intellectualism seemed bizarrely at odds with the development priorities of a large, new African nation.

These criticisms are evidently well-founded, but it is as well to remember that the university was jointly created. Fry and Drew designed the buildings and colonial officials oversaw the project; but Nigerians, albeit often a small elite, had demanded a university, secured the land for it, approved its funding, and often welcomed its buildings. Fry and Drew’s buildings have their problems: but their campus, however flawed, is surely preferable to having no university buildings at all.

Indeed, the buildings have become a barometer of the fortunes of Nigerian universities more generally. Neglected in the 1980s and 1990s as Nigeria suffered the vicissitudes of the International Monetary Fund’s structural adjustment programme and military rule, the attention currently devoted to maintaining and upgrading Fry and Drew’s buildings speaks of the cautious optimism now surrounding Nigerian universities. Despite the architects’ undoubted talents, the blank walls and patterned concrete screens of the University of Ibadan have for over fifty years reflected, mirror-like, what their viewers wanted to see in them, as much as what Fry and Drew originally visualised.

Tim Livsey is a historian who works on the relationship between architecture and development in West Africa. He recently finished an AHRC-funded PhD at Birkbeck College, University of London on the university in Nigeria in the age of decolonisation.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.