This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

Most members probably know two or three buildings by Harry Stuart Goodhart-Rendel (1887 – 1959) – but not more. Our spring walk with Alan Powers helped us understand the man and his ever-inventive work. Alan pioneered the appreciation of Goodhart-Rendel with his 1977 Cambridge thesis, then curated the definitive Architectural Association exhibition in 1987. Discussions with Goodhart-Rendel’s surviving colleagues and students (including Alan’s own father) have given him a unique insight into this complex personality and his idiosyncratic work.

Goodhart-Rendel was born into the highest echelons of society. Precociously talented, he studied music at Cambridge, but soon moved to architecture and set up his own flourishing practice. Honours and distinctions led to an unhappy stint (1935 – 38) as Director of Education at the AA in its most radical period. He converted to Roman Catholicism in 1936, and in 1945 inherited the Hatchlands estate, where he entertained architectural writers including Betjeman and Summerson. In his architecture he ploughed a lonely furrow. Following Viollet-le-Duc and the French theorists, he practised a structural rationalism that could embrace modern technologies. But he was the first to appreciate the muscular polychromy of the mid-Victorians, and often clothed his structures in patterns of brick. He was pragmatic about style, believing that a building should grow out of its circumstances and brief, yet he loved quirky geometries – we saw plenty of star-shapes and polygons. His book English Architecture Since the Regency (1953) is full of maverick judgements.

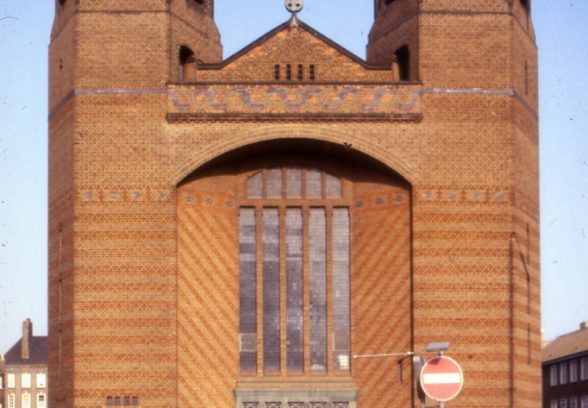

His serene last work, the church of the Most Holy Trinity, Dockhead (1951 – 60) is now listed Grade II*. This gracious basilica replaced a bombed church serving an area of Catholic dock-workers, and Bobby Drake described the context of post-war Catholic churches. Here, a wide nave with narrow aisles and an open sanctuary gave everyone a view of the altar. The overall flavour is Romanesque: German Romanesque for the twin-towered west front, southern French for the high tunnel vault on a cross-axis inspired by Tournus. The exterior is enlivened by intricate geometric patterns in buff, blue, and russet brick, while the rhythm of brick window mullions is most satisfying.

Hays Wharf of 1930 – 32 is earlier but feels more modern, and simply follows the logic of its brief. Built for a company that imported foodstuffs, it had to combine a prestige headquarters with a working wharf. Circulation routes are neatly separated. Clad in stone, it boldly expresses the horizontality of its steel frame, but is softened on the river front by a decorated panel marking the Directors’ Common and Board Rooms.

These Art Deco rooms with their imitation marble, Empire woods, and Betty Joel furniture (now lost) look out over the river through faceted bays. Goodhart-Rendel’s invention is seen everywhere: a jazzy staircase with twisted octagonal newels, a rather mad clock, and geometric patterns in the hall floor.

A boat trip took us to Westminster, where Goodhart-Rendel designed No 1 Tufton Street in 1951 – an elegant essay in Philip Webb-style Georgian which looks just right for its street. At the same date he was designing Westminster Technical College (1950 – 55) in Vincent Square. He took an existing four-storey steel frame

and clad it in two tones of London stock brick – decorating but not disguising the frame. Brick spandrel panels between the windows have lovely patterns of interlacing diagonals.

And so finally to the Anglo-Catholic heaven of St Mary Bourne Street (or Graham Street), a treasure-house of sacred art enriched in the last century by designers from Martin Travers to Roderick Gradidge. But it was Goodhart-Rendel who transformed the modest servants’ church of 1873 – 74 by adding a new north aisle, entrance, and porch in 1926. An irregular seven-sided tower subtly shifts the axis of entry, while it is hard to spot the join between his new aisle and the original church. Goodhart-Rendel’s lovely brick arches on granite springers respect the Victorian original, but add something new.

Our thanks to Alan, assisted by Bobby, for a wonderful and enlightening day.

Peter Wylde

C20 members toured the Goodhart-Rendel buildings in April 2016

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.

Comments