This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

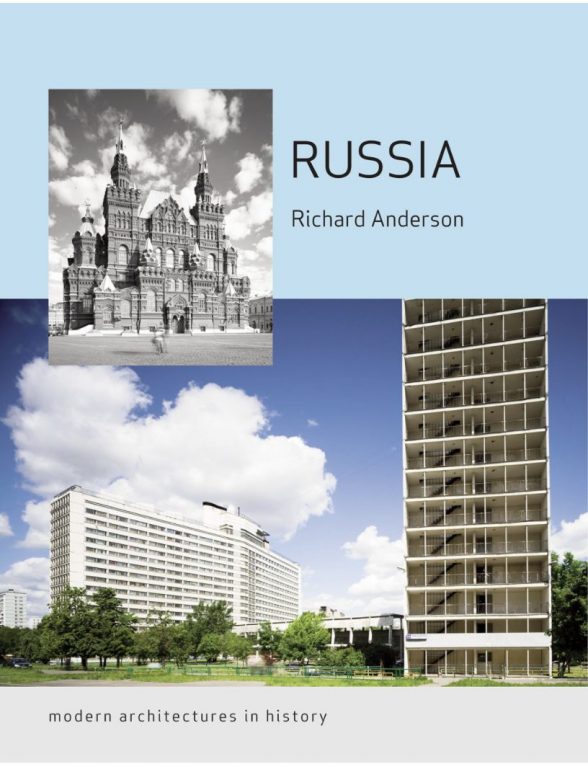

Russia: Modern Architectures in History

Richard Anderson (Reaktion, 352pp, £20)

Reviewed by Clem Cecil

This contribution to Reaktion’s ‘Modern Architectures in History’ series will go on my bookshelf beside a handful of crucial texts on Russian architecture. It is a much needed English-language book on the subject, and a valuable source for further research.

The tone is careful and measured: Anderson packs 150 years of architectural history into some 300 pages, alongside excellent illustrations. In Russia everything is only ever one step away from politics, and this makes the book particularly exciting: it is an alternative history of Russia and the Soviet Union.

He begins the history of Russian modernism in 1861, a time of reforms (the liberation of the serfs was in that year), and traces the roots of the formalisation of the architectural profession, with the opening of academies in Moscow and St Petersburg in 1867 and 1870. In his introduction he counters the divisions encountered in many histories of Russian architecture: between the 19th and 20th centuries, pre and post-revolution, pointing out links in experiments and ideas over the entire period.

He shows how modernism returned even after the period of high Stalinism that was so disastrous for the country and for the architectural profession. In 1952, a year when many prominent architects and critics suffered public denunciations, Mikhail Tsapenko ‘buried the contributions of Ladovskii, Ginzburg, Melnikov, the Vesnin brothers and many others under a mountain of grandiose rhetoric. It would take a generation for the work of these architects to be rediscovered.’ Anderson goes on to demonstrate how their rediscovery fed into the architecture of the 1970s.

Similarly, he considers Russia’s relationship with the west, and places its architecture in an international context. In the 1920s, Le Corbusier said of Moscow that it had become ‘the focus of architecture and city planning in the world’. He bought a set of blueprints of Narkomfin (Moisei Ginzburg, 1930) and used them in the design of Unité d’Habitation. Equally, despite the isolationism of the Stalin era, by the late 70s and early 80s, ‘Soviet architects participated in the broad revision of architecture’s relationship to history and historical context that unfolded in many parts of the globe.’

Another idea that persisted, though sometimes buried as being too pro-western, was that of the garden city movement, used to help solve the housing crises in Soviet Russia. In the post-revolutionary period there was no money to build on a large scale, and the garden city movement provided a vision of a realistic, sustainable city. This was also the case after WWII when the country was on its knees: the pioneering urban planner Vladimir Semenov, author of the 1930s new General Plan for Moscow, was a great supporter of the movement.

The book establishes other landmark figures, buildings and events: for example Ivan Fomin, a brilliant classicist who experimented with the New Style at the turn of the century, immersed himself in rigorous classicism, embraced modernism in the 1920s and returned to classicism in the 1930s. He was a giant of Russian architecture whose influence and stature I had not previously grasped. Anderson also mentions Viacheslav Oltarzhevskii, whose experience working in New York from 1924 to1935 was so crucial to the construction of Moscow’s Stalin-era ‘seven sisters’ in Moscow (despite the anti-American rhetoric of the time), yet he had been arrested a decade earlier after completing the design of the All-Union Agricultural Exposition (1939).

Anderson seeks to go beyond Russia to look at Soviet architecture and counterbalance the highly centralised nature of the Soviet Union, in which architects emanated from Moscow or Leningrad (now St Petersburg). However, precisely because of this, most of the book is about Moscow. As he acknowledges, Moscow was at the forefront of architectural experimentation and change throughout the period, especially after it became the capital again in 1918.

He writes that ‘Stalin’s revolution produced both social devastation and utopian aspirations – the two often went hand in hand.’ I would have liked a little more about the extent of demolition required to remodel Moscow as a Soviet city and to keep reinventing it throughout the 20th century: further information about what has and has not been demolished would have been useful, from both a historical and practical point of view. The rate of destruction is potentially hard to keep track of: for example Dinamo stadium (1927-28) was demolished in 2011.

On the state of Russian architecture today, Anderson quotes leading Russian critic Grigorii Revzin who says it is caught somewhere ‘between the USSR and the West.’ He also charts the influence of Soviet institutions in today’s practices, noting that the dominance of Soviet-era municipal design bureau Mosproekt-2 in Moscow today indicates the ‘strong institutional continuities within the design and building complex that extend across the divide of 1991’ and a ‘centralised design administration.’

This is a highly successful, highly readable history told with passion. It opens up new avenues of research and frees us from some previously-held and limiting ideas. It is a level-headed, intelligent assessment that broadens the range and depth of understanding of Russia’s architecture.

We are still populating our book review section. You will be able to search by book name, author or date of publication.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.