This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

January 2018 - Allbrook House and Roehampton Library, London

by Geraint Franklin

The Roehampton Lane estate, designed by Bill Howell, John Killick, John Partridge and Stan Amis, was one of the jewels in the crown of the London County Council’s feted post-war housing programme. Its magnificent site conjoined the grounds of three 18th century houses fringing Richmond Park: Mount Clare (boasting Capability Brown landscaping), Manresa House and Downshire House. In accordance with LCC housing policy, a mixture of dwellings and building heights was provided to meet the stipulated density including wide slab blocks of maisonettes, slender point blocks, low-rise terraces and bungalows. Using a scale model the architects composed a layout which respected the site’s topography, while Partridge’s landscaping enhanced the picturesque landscape setting. The monumental centrepiece was Howell’s five maisonette blocks that stand over Downshire Hill, their form and grouping inspired by Le Corbusier’s 1945 plan for Saint-Dié.

In the layout approved by the Minister of Housing in 1953, the estate greeted the old village of Roehampton Lane with an open space, loosely enclosed by shopping terraces and a tall ‘marker slab’ of maisonettes – Allbrook House. ‘We were at great pains not to destroy the village as a centre but to extend it’, explained the LCC’s principal housing architect, H.J. Whitfield Lewis in 1956. ‘We have carried on the High Street as one of the main entrances to the estate and made a major extension of the Roehampton Village shopping centre to the south of the main road. […] That will create a large piazza and will be a focal point in the scheme’.

The alignment of Allbrook House marked a pronounced fall in ground level to the west, and a branch library, structurally-independent of the slab, slid neatly under its piloti in a manner reminiscent of Le Corbusier’s Ministry of Education and Health building in Rio. Vehicular and fire brigade access to the residential block, required at one storey above the street level of Danebury Avenue, took the form of a sinuous access ramp, terminating in a ‘banjo head’ turning circle.

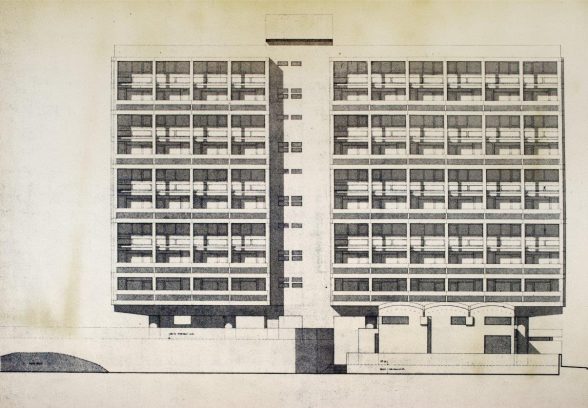

Allbrook House (working title: ‘Block 21’) was a one-off design developed by Partridge with reference to Howell’s maisonette blocks and contemporary slabs by their Corbusian allies in the architect’s department: Bentham Road in Hackney (by Colin St John Wilson, Peter Carter and Alan Colquhoun) and Loughborough Road in Brixton (Wilson, Carter, Colquhoun and Jill Sarson, Howell’s wife). It was detailed by Roy Stout, who had asked to join the Roehampton team in 1954 having seen a published plan. While its narrow frontage (12 foot) bays followed those of Howell’s blocks, the overall proportions were more compact, being of 11 bays and ten storeys as opposed to 16 bays and 11 storeys. In addition to the four storeys of maisonettes the LCC planners asked for an extra floor of single-storey flats to make up for a building demolished elsewhere.

Constructed in 1959-61, Allbrook House benefited from a slightly more generous budget than Howell’s blocks, permitting a reprise of the cantilevered end bay of Bentham Road and pierced pre-cast balustrades, both directly inspired by Corbusier’s Marseilles Unité, a pilgrimage site for the LCC Corbusians. Another innovation was the brise soleil introduced on the balcony side, while the lift and stair core was expressed as a recessed bay finished in board-marked concrete. The structural design follows Howell’s blocks, with partitions carrying service ducts alternating with structural cross-walls; a distinction not expressed in the elevations.

Although the design of the library was the responsibility of Wandsworth Borough Council, the LCC architects insisted on keeping the job in-house, so integral did they feel it was to the group. Detailed by Stout from an initial doodle by Partridge, its design was based on a cluster of domes of thin shell concrete construction. Glass lenses sunk into the domes illuminate bookcases planned on bay divisions. The combination of shallow domes and top light, so different from the rest of the estate, recalls John Soane, with whose work Partridge was familiar, and who had also influenced Philip Johnson’s Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery at the University of Nebraska of 1958–63.

A central entrance gives access to a children’s’ library of 3×2 bays and an adults’ reading room of 9×9 bays. Stout recalled that the original intention was to keep the elevations entirely blind but Wandsworth insisted on advertising their library service to residents. Unlike any other building at Roehampton Lane, the exterior was rendered in mineralite, a cement-based render developed by Blue Circle incorporating mica for a twinkly finish. The library was opened in September 1961, its interior featuring Muninga hardwood block floors and a wax resin mural by LCC consultant artist Bill Mitchell.

The piazza was completed by two adjacent shopping terraces (block 50 and the shorter 50A to the east, which boasted a co-op supermarket). The design drawings of 1956-7 suggest the involvement of Edward Reynolds, a talented but unqualified assistant who went on to study at the Architectural Association at Howell’s suggestion. The shopping parades are punctuated by narrow staircase bays which give access to three storeys of balcony-access flats and maisonettes. They are constructed from reinforced concrete frames and cross walls with brick infill panels. The attenuated pre-cast framework of the balconies, with their chunky horizontal rails, clearly relate to Howell’s maisonette blocks. But it was the stepped rear elevations, detailed in shuttered concrete, which Nikolaus Pevsner singled out as the most avowedly Brutalist element of Roehampton Lane:

Brutalism is a label which ought perhaps to be avoided. Yet the details of the end walls and the backs of the shopping terraces at Roehampton have that pride in beton brut and that delight in chunky shapes which justified the term in reference to Le Corbusier at Chandigarh and to this most recent part of the Roehampton Estate.

* * *

When the estate was assessed for listing by English Heritage in the mid-1990s, the five maisonette blocks on Downshire Hill were listed at Grade II*, joined by several low groups of bungalows for the elderly, at Grade II. The boundaries of the Alton Conservation Area, designated in March 2010, cover much of the Roehampton Lane and Portsmouth Road estates (or Alton West and Alton East as they were later known), but exclude the shopping piazza. Wandsworth Council’s Alton Area Masterplan of October 2014 proposed major interventions including the demolition of the area adjoining Roehampton Village. In 2015 a listing application for Allbrook House and Roehampton Library was rejected by the DCMS on the advice of Historic England.

* * *

Geraint Franklin’s Howell Killick Partridge & Amis (Historic England, 2017) includes a chapter on Roehampton Lane. This book forms part of a series of books on 20th-century architects produced in collaboration between Historic England, the Twentieth Century Society and RIBA Publishing.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.