This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

Margherita Manca explores the candid and colourful notebooks of the Italian architect Giancarlo De Carlo.

To mark the centenary of the architect and urbanist Giancarlo De

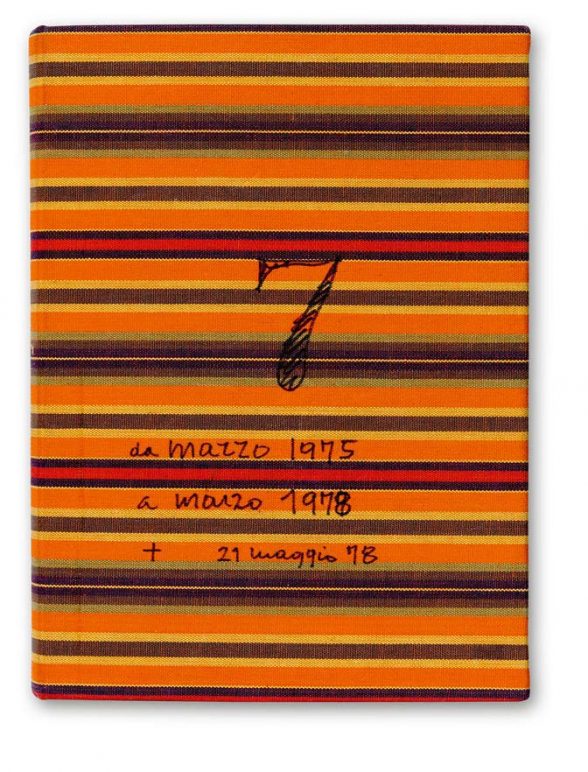

Carlo (1919–2005), the Triennale Design Museum in Milan recently hosted an exhibition featuring sixteen of his personal notebooks. These extensive, colourful diaries, written from 1966 until his death, record his worldwide travels as well as his personal and work relationships. Transcribed for the exhibition by his daughter Anna and featuring a mixture of collage, pop-up and illustration, they reveal the opinionated, creative and sometimes anarchistic character behind the professional architect.

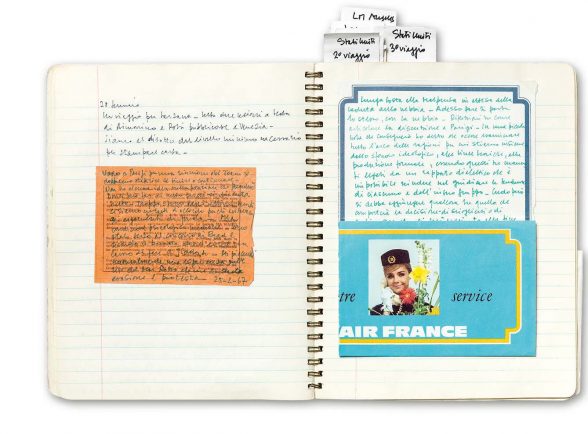

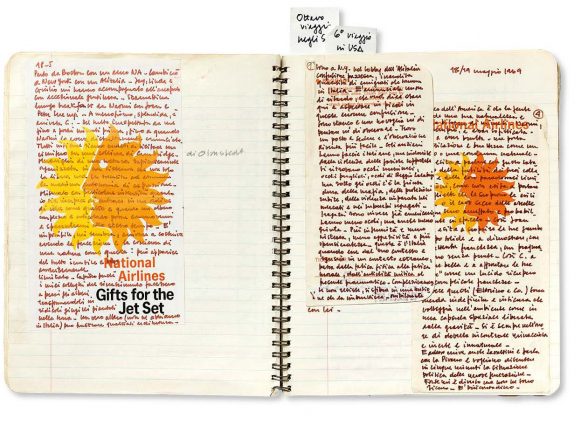

Each diary is a design object in its own right, with different coloured inks, sketches and added pieces of paper. Collage becomes a way for the writer to signal his location, often in transit. He scribbles his musings on hotel letterheads from Switzerland to Yugoslavia, or visually striking airline ephemera such as the American National Airlines Sun King logo or a turquoise Air France promotional card. He candidly records his views on contemporary events like the social revolutions of 1968, and the buildings he sees on trips to Japan and the United States.

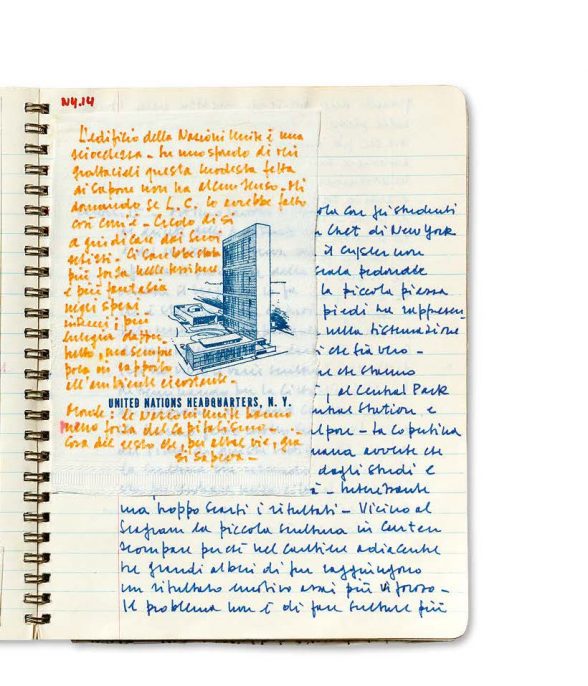

In notebook number four, for instance, he is unimpressed by the United Nations building in midtown New York, calling it

‘foolish’ and ‘nonsensical’, and suggests that ‘L C’ (Le Corbusier)

would have designed it better if he had been in sole charge of the project (in fact he was just one of the committee of architects that included Oscar Niemeyer and Wallace Harrison). Writing in

orange ink on a UN-branded piece of paper on another page, De Carlo says that, in his view, the master of modernism would on his own have given ‘more strength to the building’s textures’.

In the Triennale gallery, visitors could take a seat in a stylised

version of the ‘Salotto di Casa Sichirollo’, designed by De Carlo

in the late 1960s for himself and his friends, Livio and Sonia Sichirollo, in Romanino near Urbino – the Italian city where he practised for many years. The message that those visitors would probably have taken away was that by looking beyond the brick and mortar constructions of architects to their constructions of a more ephemeral kind – such as De Carlo’s notebooks– we gain a deeper understanding of who they were.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.

Comments