This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

Much of C20 architecture is characterised by unique details. This series of photographs accompanied by their authors’ thoughts was first posted on our Instagram and celebrates them. Details include striking door handles, mesmerising lighting, distinctive windows and modern clocks from around the world.

Elain Harwood

Twitter: @elain540

“I’ve long been bemused by the entrance doors at the Royal Festival Hall (Robert Matthew, Leslie Martin and Peter Moro, London County Council; 1948-51).

They have a disturbing touch of whimsy, a reminder that Mid-Century Modern has one source in the romantic Regency revival of the late 1930s/40s.

This is especially true of the RFH monogram by Jesse Collins of the Society of Industrial Artists. Presumably the commission came from Robert Matthew as architect to the council, but this is by no means clear.

Although the doors swing both ways, there are doorplates only on one side, a subtle control of the direction of traffic that had its sources in Scandinavia.

The best example I know is at Gunnar Asplund’s Stockholm City Library (1924-8), where handles on opposite sides of double doors take the form of Adam and Eve.”

Elain Harwood is a senior architectural investigator with Historic England, specialising in the twentieth century. She is the author of Space, Hope and Brutalism (2015) and Chamberlin, Powell & Bon (2011). In 2019 she published Art Deco Britain and is now writing a sequel, Mid-Century Modern, featuring the Royal Festival Hall.

Adam Štěch

Instagram @okoloweb

“Julio Vilamajó was one of Uruguay’s most important architects of the last century. Thanks to his contacts with Le Corbusier and other international modernists, Vilamajó was one of the first to introduce modern style in Uruguay during the 1920s.

Yet he has not given up on local inspiration and his buildings represent a unique synthesis of international modernism, Art Deco and local building traditions and colonial style.

Today, his own 1930 Montevideo house is open to the public [Museo Casa Vilamajó].

In its reconstructed interiors, visitors can see unique details that demonstrate Vilamajó’s decorative touch. The ceiling light in the main living area with its colourful glass beads resembles a precisely made jewel.”

Adam Štěch is an art theoretician, writer, and curator based in Prague. He is a co-founder of the creative collective OKOLO, responsible for dozens of design publications and exhibitions in the Czech Republic and abroad. His forthcoming book Modernist Architecture and Interiors (Prestel Verlag, June 2020) promises to be the definitive guide to architecture in the 20th century in all its different forms and tendencies.

Catherine Croft

Instagram: @catherine.c20

Twitter: @catherinecroft

“St Paul’s Lorrimore Square was designed by John Wimbleton of Woodroffe, Buchanan and Coulter, and consecrated in 1960.

It’s the most idiosyncratic C20 building close to where I live, and one I love.

It stands at the centre of the Brandon Estate, notable for being the first LCC estate where extensive rehabilitation of C19 houses was combined with bold new build.

The church is raised above parish rooms and social facilities and incorporates stone from the bombed Victorian church by J. Jarvis’s (1854-6), previously on the same site.

Both the honeycomb concrete block walls (glazed with coloured glass) and the copper clad roof are highly distinctive features.

As Joshua Mardell points out in his C20 Building of the Month [October 2010] piece, ‘the roof at St. Paul’s makes as much a theological statement as a technological one, the triangular structure representing the importance of the Trinity in Eucharistic worship.’

If it looks familiar you may be recalling it from our 2017 AGM, or you may have seen it as a key location in the excellent TV series London Spy (2015) starring Ben Whishaw and Charlotte Rampling.”

Catherine Croft is Director of the Twentieth Century Society, the author of Concrete Architecture (2004) and co-author of Concrete – Case Studies in Conservation Practice (2019).

Richard Walker

Instagram:

@richardwalkerworks

@richardwalker.art

@richardwalker.shop

“Every day I walk around (or under) this extraordinary piece of sculpted concrete.

This is a turret linking the glass walkways of Goldfinger’s Metro Central Heights formerly Alexander Fleming House, built 1958-64, home to the Ministry of Health at the Elephant and Castle.

It was converted into flats in 2003, it was listed in 2013, and now, for me, is an inspirational place to live with spectacular views across London.”

Richard Walker is an artist based in London. His first solo exhibition was at Minsky’s Gallery in Primrose Hill on Valentine’s Day in 1978. After many trips across the Atlantic and a developing interest in cities and architecture, Richard exhibited in America and many times in Germany. Always personal, but also accessible, his images are about locations, physicality, structures and memory. Richard’s interest in architecture has led him to be an active tour leader with the The Twentieth Century Society and his ‘Up the Elephant’ walk is a perennial favourite.

Owen Hatherley

Instagram: @owenthomashatherley

Twitter: @owenhatherley

“I knew the ‘detail’ I would pick would be from the London Underground stations from the Charles Holden/Frank Pick era, between the 1920s and 1940s, but I wasn’t sure which it would be.

It could have been the travertine panelling of Piccadilly Circus, the concrete lighting and advertising stands on the outer reaches of the Piccadilly Line, the stained glass at Uxbridge, or the roundel capitals on the southern stretches of the Northern Line.

But the detail I’ve opted for can be found in each of the stations on Holden’s short late 40s extension to the Central Line (Gants Hill, pictured, Newbury Park, Wanstead, Redbridge).

Each of these has at platform level a big clock.

On it, each of the 12 hours is signified by a colourful, abstracted London Underground roundel, a motif also used on the small hand of the clock.

A branding exercise, for sure, but also an image of a benevolent bureaucracy, committed to helping Londoners travel through and understand their almost limitless, unknowable metropolis, every hour of the day.”

Owen Hatherley is a London-based writer and journalist who writes primarily on architecture, politics and culture. His two most recent books were Trans-Europe Express and The Adventures of Owen Hatherley in the Post-Soviet Space, both published in 2018. Owen’s forthcoming Red Metropolis (Repeater Books, December 2020), a polemical history of municipal socialism in London, will argue for turning London “red again”.

John Grindrod

Instagram: @johngrindrod

Twitter: @Grindrod

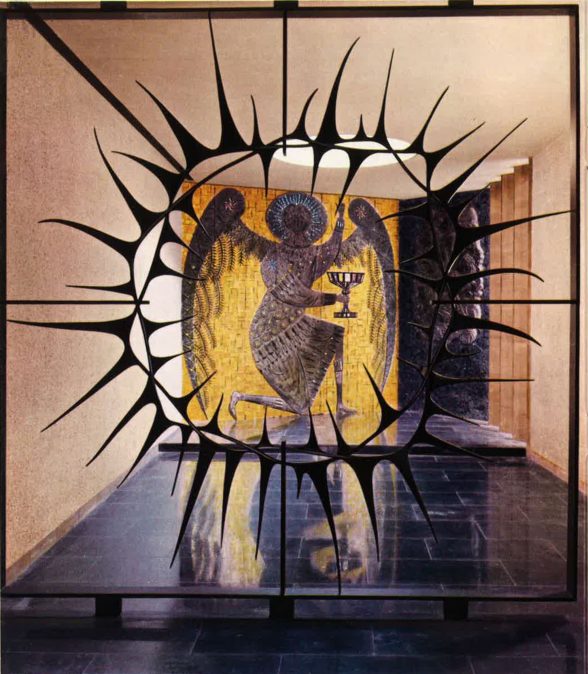

Photo: The Art of Coventry Cathedral; 1962

“This large wrought iron barrier in the Chapel of Christ in Gethsemane, Cathedral Church of St Michael, Coventry, was designed by Basil Spence and reflects artwork by many of the artists he commissioned for the Cathedral.

It’s in the form of a ring of thorns; its shape brings to mind many of Graham Sutherland’s painfully powerful paintings of the period.

There’s a rawness to it that chimes with Elisabeth Frink’s brawny eagle, and a transparent lightness that reflects John Hutton’s astonishing glass wall of angels.

Spence’s ironwork was made by the Royal Engineers, one of many links connecting war with peace throughout the building and the city beyond.

As a symbol of transcendence over pain, this thorny screen is a reminder of the power that smaller, quieter details can have in great modernist buildings.”

John Grindrod is the author of Concretopia: A Journey Around the Rebuilding of Post-War Britain (2013), Outskirts: Living on the Edge of the Green Belt (2017), and How to Love Britalism (2018), and contributed an introduction to The Town of Tomorrow: 50 Years of Thamesmead (2019).

Barnabas Calder

Instagram: @barnabascalder

Twitter: @BrutalConcrete

“This is a drainpipe from a wonderful block of flats on the Via Piagentina [Edificio residenziale di via Piagentina] in Florence, designed by Leonardo Savioli and Danilo Santi, and built 1964-7.

The architects have taken the drainpipe indoors for the lowest floor, photo 2, presumably to protect it from street-level wear and tear.

Their commitment to brutalist ‘honesty’ is so great that they have added a window beneath the chunky concrete gargoyle to show you where the pipe has disappeared to.

It is robust in detail, but delicate in thinking.”

Barnabas Calder is a historian of architecture specialising in British architecture since 1945 and Senior Lecturer at the University of Liverpool. He is the author of Raw Concrete: The Beauty of Brutalism (2016) and the forthcoming Architecture and Energy: From Pre-history to Climate Crisis (Pelican, autumn 2020).

(More photos of the buildings: search “Savioli and Santi flats” on Flickr.)

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.

Comments