This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

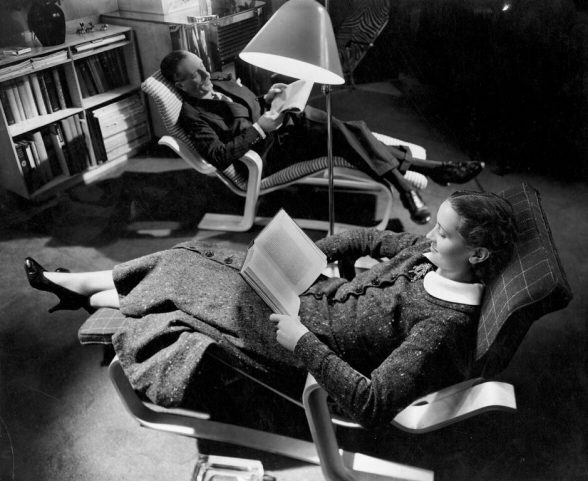

Photo: The Christie Archive Trust

The Isokon Gallery’s Agatha Christie and the Modernist War Years exhibition runs until the end of October 2022.

Leafing through the Lawn Road Flats’ tenants’ list for the year 1941, a new entry appears for Flat 20: “Mr and Mrs Mallowan”. Although registered under her married name, Mrs Mallowan was perhaps better known as Agatha Christie, the best-selling novelist of all time. The six years between 1941 and 1947 Christie spent living in the Hampstead flats, were amongst the most productive of her career. It was here in 1946 that she wrote the radio play which became The Mousetrap, the world’s longest-running stage play. It was also here that she killed her much-loved and eponymous hero, in Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case, a book which she kept locked in a bank vault for 30 years.

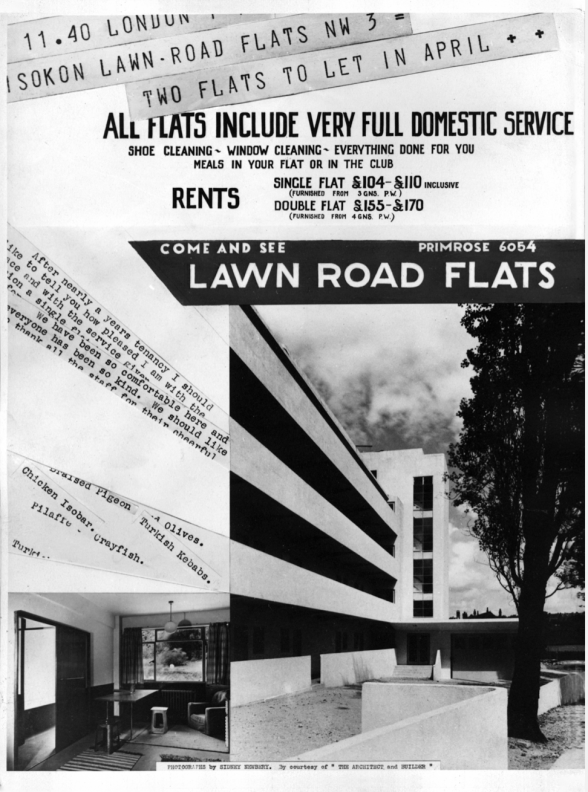

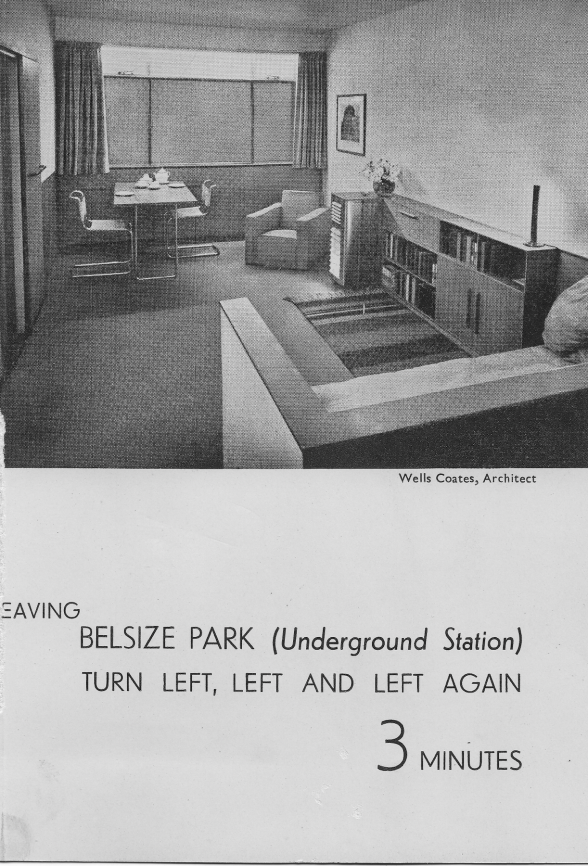

Designed by Canadian architect, Wells Coates, The Lawn Road Flats, now known as “The Isokon”, Britain’s first reinforced concrete apartment building, opened in 1934. Commissioned by entrepreneur Jack Pritchard and his psychologist wife, Molly (who wrote Coates’ brief), the 32 “Minimum Flats” were designed as a new experiment in social living. They were aimed at “young professional men and women earning around £500 a year”, who could move in with just “a vase, a rug and a favourite painting”. Inspired by Coates’ and Pritchard’s 1931 visit to Germany (where they had visited the Dessau Bauhaus and housing developments in Berlin and Stuttgart) the compact 25m² serviced apartments, consisted of a studio room, bathroom, dressing room and compact kitchen. Modular furniture could be purchased from Pritchard and Coates’ company, Isokon and meals were initially provided from a central kitchen – later replaced by the Isobar restaurant and dining club, run by Britain’s first television chef, Philip Harben. In 1934, Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius fled Nazi Germany and moved into the Flats, to be joined the following year by his colleagues Marcel Breuer and László Moholy-Nagy. Within a year of their opening, Pritchard had three of the greatest names of Modernism living in his new building and working for his fledgling Isokon Furniture Company. In 1936, Breuer designed a range of plywood furniture for Pritchard, including the Long Chair, short chair, nesting tables, a dining table and dining chair.

Photo: Pritchard Papers / UEA

By the outbreak of the Second World War, Agatha Christie and her husband, the eminent archaeologist Max Mallowan had an extensive property portfolio. However, their London home, a four-storey detached house at 58 Sheffield Terrace in Kensington was damaged early in the Blitz and their country house, Greenway in Devon, was requisitioned by the Admiralty for the American navy. In Autumn 1940, Jack Pritchard had begun advertising the Lawn Road Flats, with its reinforced concrete structure, as “the safest building in London” and soon had a flood of new applicants, including the Mallowans. Christie already knew two of the tenants – Egyptologist Professor Stephen Glanville and the young architect and goldsmith, Louis Osman, who had carried out some alterations to her house in Wallingford in Oxfordshire. Osman, who had been awarded RIBA’s Donaldson Medal on graduating from the Bartlett, would later, design the Prince of Wales’ crown at his investiture in 1969.

Christie described the impression the Flats made as she approached them along Lawn Road:

“Coming up the street the flats looked just like a giant liner which ought to have had a couple of funnels, and then you went up the stairs and through the door of one’s flat and there were the trees tapping on the window.”

Photo: Pritchard Papers / UEA

In March 1941, she and Mallowan moved first into Flat 20 and shortly afterwards into Flat 22. For the next year, Mallowan worked for the Directorate of Allied and Foreign Liaison, the intelligence branch of the RAF, while Christie (a qualified apothecary) took a job with the Voluntary Aid Detachment in the chemist’s dispensary at University College Hospital. Mallowan described their first Wartime year together in the Flats as “eventful, exciting and amusing”. In 1942, he was posted to Cairo. It was the first time in the decade since their marriage that the couple had lived apart. In her husband’s absence, Jack Pritchard allowed Christie to keep a Sealyham terrier, James, for company and she walked him on Hampstead Heath and took him into work at the dispensary at UCH. She recalled:

“Lawn Road Flats was a good place to be since Max had to be away. They were kindly people there. There was also a small restaurant with an informal and happy atmosphere. Outside my bedroom window, which was on the second floor, a bank ran along behind the flats planted with trees and shrubs. Exactly opposite my window was a big, white, double cherry tree which came to a gret pyramidal point.”

Christie buried herself in her writing, sometimes working on two books simultaneously. Although her study in Sheffield Terrace had been large enough to hold a Steinway grand piano, she adapted well to the modern, pared-back simplicity of her minimum flat furnished with Marcel Breuer’s plywood Isokon designs and found it conducive to her work. She wrote to her husband that she liked to:

“Lie back in that funny chair here which looks so peculiar and is really very comfortable, close my eyes and say, ‘Now where will I go to with Max?’ Often it is Leptis Magna or Delphi, or up the mound at Nineveh.”

Photo: Pritchard Papers / UEA

Christie had accompanied Mallowan on his archaeological digs in the Middle East and studied photography at the Reimann School of Art and Design in London, in order to document his finds. She was a keen observer, who drew upon the people and places around her in her work. Her time at Lawn Road coincided with a fascinating cohort of international residents, who included the Czech designer Jacqueline Groag and her architect husband Jack Groag, Austrian architect and designer Egon Riss, the New Zealand political cartoonist David Low and Eva Collett Reckitt, founder of the left-wing bookshop Collets.

“I never found any difficulty writing during the War, as some people did,” she recalled.” I suppose because I cut myself off into a different compartment of my mind. I could live in the book amongst the people I was writing about, and mutter their conversations and see them striding about the room I had invented for them.”

N or M and Evil Under the Sun were published in 1941, followed by The Body in the Library in 1942, The Moving Finger in 1943 and Towards Zero in 1944. The book she was most proud of was Absent in the Spring, which she wrote in three days flat and published in 1944 as one of her Mary Westmacott novels. It was a psychological study about a woman alone in the desert. Death Comes to an End and Sparkling Cyanide were released in 1945 and The Hollow in 1946. Her short stories from this era included The Crime in Cabin 66 of 1943, and the Hercule Poirot adventures: Poirot and the Regatta Mystery; Poirot on Holiday; Problem at Pollensa Bay and the Christmas Adventure. The Veiled Lady and The Mystery of the Baghdad Chest arrived in 1944; Poirot Knows the Murderer in 1946. In addition, she penned an autobiographical memoir entitled Come, Tell Me How You Live in 1946, about her travels and archaeological work with her husband to Syria and Iraq.

The Lawn Road period is also significant for Christie’s successful dramatization of several of her works for the stage, including And Then There Were None… which opened at the St James’ Theatre in October 1943 and as Ten Little Indians on Broadway in June 1944. Appointment with Death premiered at the Piccadilly Theatre in March 1945 and Murder on the Nile which opened at the Ambassadors Theatre in March 1946.

As the War progressed, Pritchard painted the building, which was originally a Coates-specified shade of the palest pink, dark brown to camouflage it from the Luftwaffe. During the night-time air raids many residents left their flats and sheltered in the convivial atmosphere of the Isobar, drinking and dancing the night away. Christie, however, preferred to remain alone in her apartment: “face covered with a pillow as protection against flying glass, and on a chair by my side, my two most precious possessions, my fur coat and my hot water bottle…thus I was ready for all emergencies.”

Mallowan returned from Cairo in May 1945 and although by December Greenway had been derequisitioned, the couple kept Lawn Road as their London base. Keen to have more space, they asked Jack Pritchard if they could link Flats 16 and 17 by knocking down the party wall. He granted them this unique dispensation and they stayed on in the building until June 1947. The affection with which they regarded the Flats is revealed in a letter which Christie wrote to her husband.

“How odd to think that as I pass a funny old building like a liner I shall always look up at it and say to myself “I was happy there!” No beauty to speak of…but oh darling I did have so much happiness there with you.”

Agatha Christie wrote Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case during her War years at Lawn Road. Fearing for her own life and wanting to ensure her character met a fitting end, she locked it away for 30 years. Originally intended for release only after her death, it was published in 1975. Agatha Christie died the following year. Her books have sold over a billion copies in the English language and a billion in translation.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.

Comments