This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

May 2024 - Earth Centre, Conisbrough, South Yorkshire

Image credit: ZedFactory

Earth Centre, Conisbrough, South Yorkshire (1994-2001)

Feilden Clegg Design, Grant Associates, Alsop and Störmer, Letts Wheeler, Bill Dunster Architects, and Future Systems

By Tom Goodwin

In 1987 the Brundtland Commission of the United Nations published Our Common Future, begetting the concept of sustainable development – meeting ‘current demands without jeopardising future generations’ ability to meet their own needs’. This formulation immediately gained widespread support, capturing the imagination of the publisher and museum campaigner John Letts. Letts decided to establish a Museum of the Earth dedicated to sustainability and environmentalism, with the London Docklands and Giles Gilbert Scott’s monumental Bankside Power Station discussed as potential sites.

Instead, one hundred and sixty hectares of blighted land – the former sites of the Cadeby and Denaby Main Collieries, and the Kilner Providence Glassworks – was leased from Doncaster Council in 1991. The choice of location fell to the Yorkshire-born Jonathan Smales, who had left his job as director of Greenpeace UK to set up the museum. Under his aegis, there had been an unprecedented growth in Greenpeace’s media profile and membership, as well as a major capital project, with Feilden Clegg Design converting a former animal testing lab into a new, low-energy HQ for the charity.

Smailes called on Feilden Clegg once more, employing them alongside the landscape architect Andrew Grant to devise a masterplan for the Earth Centre. Jan Kaplický of Future Systems and Will Alsop were also involved at an early stage, workshopping ideas with Smales and Peter Clegg on site, but failed to play an active role in the masterplan’s gestation.

Image credit: Solaripedia

In 1994, land reclamation work commenced, with the contaminated spoil buried beneath excess topsoil from a nearby construction site, sewage sludge, and waste from mushroom cultivation. In October of the following year, Virginia Bottomley, Secretary of State for National Heritage, announced that the Millennium Commission had granted the Earth Centre £50 million of match funding towards its £125 million budget. Bottomley celebrated the news by proclaiming the Earth Centre ‘the largest education complex built in the UK since the Victorian museums in South Kensington’ and stressed its strategic importance to Britain’s ambition to become a world leader in green technologies.

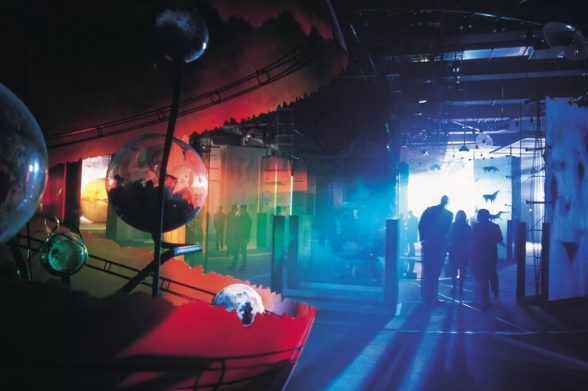

The Earth Centre was officially opened in April 1999 and housed a range of exhibitions and activities focused on the ‘principles and values’ of sustainable development, as well as the ‘creative and often ingenious solutions’ necessary to achieve it. The most fantastical example of this was the ‘Planet Earth Experience’ in the Feilden Clegg-designed Planet Earth Galleries. The team of American creatives and designers behind the experience entirely rejected a white cube approach in favour of a metaphorical (if not hallucinatory) rendering of the story of humankind and nature’s intertwined relationship. This included a series of fractured models of the globe and a glazed ‘Cyber Henge’ filled with abstract sculpture, all by the set designer George Tsypin. Sensors spread across the room allowed the lighting, soundscape, and position of the henges to change in response to the movement and position of people within the gallery

Image credit: Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios

The Earth Centre buildings themselves were intended as exemplars of environmentally conscious, modern architecture, with Smales keen to avoid ‘tweedy, woolly buildings’. In this regard, Feilden Clegg’s half-buried Planet Earth Galleries was the most cutting-edge building in phase one. As slab foundations were a pre-requisite due to poor ground conditions, the environmental engineers, Atelier Ten, had the foundations sunk a further 1.5 metres, so they could introduce a concrete ‘labyrinth’ below the main floor slab. The concrete’s high surface area and thermal mass make the air forced through it cooler in summer and warmer in winter. Plans to build the gallery’s external walls from earth proved unfeasible, so limestone sourced from a neighbouring quarry had to be used instead.

Almost a third of the energy required by the Planet Earth Galleries and the adjacent café block was provided by a ‘Solar Canopy’, which straddled the plaza between the two buildings. Upon completion in 2001 this was the largest single solar collector in the UK, with 250 photovoltaic cells atop an irregular space frame formed from 800 Scottish larch poles.

Image credit: Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios

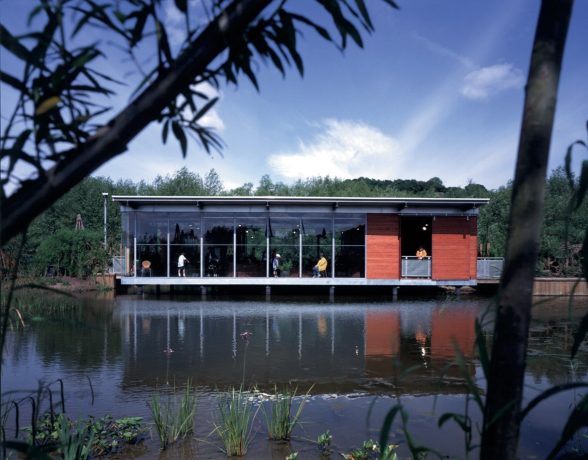

Set away from the plaza, the new practice of Letts Wheeler designed the Nature Works building, a restrained pavilion with a bucolic, waterside location. It was built with limited servicing, providing a simple, functional space where children could pond dip and examine flora and fauna gathered from across the Earth Centre’s extensive site.

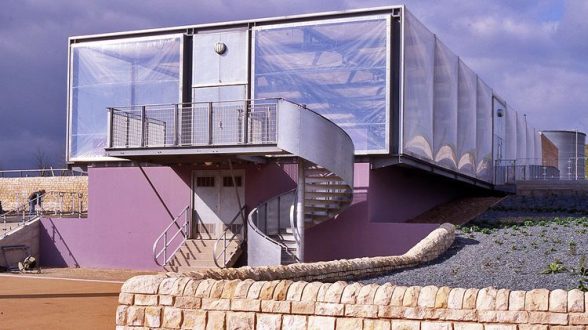

Meanwhile, Alsop and Störmer designed the Water Works building, making use of EFTE foil (the same material used at the Eden Project) to form a greenhouse-like structure atop a series of large tanks. These tanks were filled with aquatic plants and bacteria, which worked with an anaerobic digestor to clean all of the Earth Centre’s wastewater and sewage before discharging it into the River Don.

Image credit: Martine Hamilton-Knight

Image credit: Solaripedia

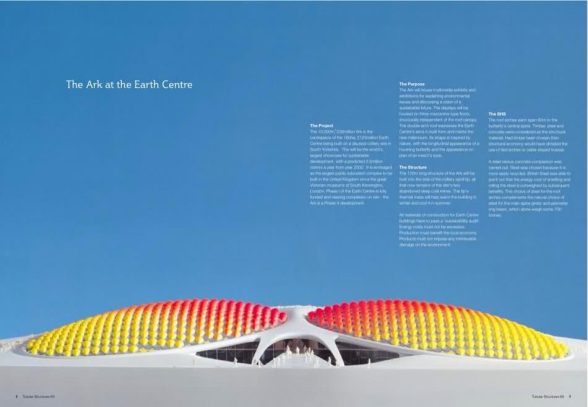

Upon opening in 1999 the centre fell well short of its projected visitor numbers and Millennium Commission funding evaporated. To the chagrin of many architectural journalists, this resulted in the scrapping of Future System’s ‘Ark’. Bug-eyed in plan and butterfly-like in elevation, the Ark would have boasted a footprint twice that of St Paul’s Cathedral, containing three floors of exhibition space devoid of columns and corners. It would have been flooded with diffused, natural light, entering the building through domed roofs, clad in glazing and solar panels. For Smales, the Ark was as aesthetically and technologically revolutionary a prospect as Paxton’s Crystal Palace had been for the Victorians. Three Alsop buildings, including a river-spanning restaurant, an EFTE-clad tower, and a hotel, were also quietly shelved.

Image credit: The Earth Centre

Instead, the final phase of construction was entrusted to Bill Dunster, formerly of Hopkins and Partners. He designed a conference centre – part of a ploy to increase the Earth Centre’s commercial offer – as well as a small entrance building across the river from the rest of the centre. Dunster focused more on the embodied carbon of his buildings than his peers, using salvaged radiators for heating, telegraph poles as structural members, and two thousand tonnes of concrete from a demolished colliery to form the gabion walls of the conference centre. Additionally, the series of cowls studding the conference centre’s sedum roof were designed to pivot with the wind, providing natural inlet and extract ventilation. They were also used at Dunster’s BedZed housing development, which was being built at the same time

Image credit: ZedFactory

The Earth Centre struggled to convert environmental sustainability into economic sustainability. In 2004 the site was handed back to the council, who let it out for use as a film set and venue for airsoft fights. The Earth Centre eventually reopened as a residential and outdoor activity centre for school groups in 2012.

As the Earth Centre floundered, many compared it to the flourishing Eden Project. For Glenn Strachan, the centre’s former education officer, the Eden Project had a clarity of purpose – seeing ‘amazing plants in amazing settings’ – that the Earth Centre could not match, as it had to discuss everything related to sustainable development. Meanwhile, the Yorkshire-born author Margaret Drabble chalked it up to taste and geography: ‘Nobody thinks you are mad if you say you are going on holiday to Cornwall. But South Yorkshire – that’s another matter.’

Tom Goodwin is an Assistant Heritage Consultant at Purcell and volunteer at the Twentieth Century Society. He is about to start a PhD looking at the architecture of the 1990s and early 2000s at the University of Warwick.

Building of the Month is edited by Joe Mathieson; an Architectural Adviser at the Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust, writer and C20 volunteer.

For pitches, or to discuss ideas for entries, please contact: joe@c20society.org.uk

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.