This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

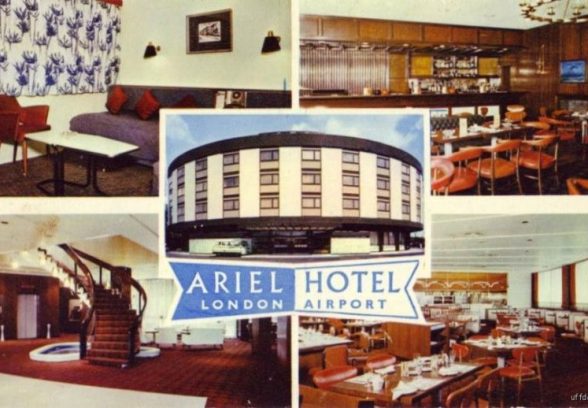

July 2012 - Ariel Hotel, London Airport

Philip Russell Diplock & Associates, 1961 by Bruce Peter

Britain’s first significant airport hotel ‘happened’ almost by accident, through a change of heart on the part of the operator, J. Lyons & Co.

Founded in 1887 as a subsidiary of the Salmon & Gluckstein tobacco company, the Lyons business expanded thereafter. Come the latter-1950s, it was Britain’s largest and most prominent food manufacturing, restaurant and hotel company, thanks largely to their tea shops and Lyons Corner House restaurants that were features of nearly every British high street. During the 1930s they had applied art deco stylings to their Lyons Corner Houses, which became popular resorts for a broad spectrum of the urban British public who were familiar with such settings from Hollywood movies and, thanks to J. Lyons, now could enjoy luncheons and dinners in romantic environments which allowed them briefly to fantasise about being their favourite screen idols.

Observing that car ownership in Britain was rising rapidly among the increasingly prosperous middle classes, in 1957, J. Lyons set up a new hotel-operating subsidiary called Palace Hotels (using the ‘surname’ of their prestige London Regent Palace and Strand Palace properties). The intention was to build the first of what might eventually become a chain of American-style roadside motels at key points on busy suburban arterial roads, linking major cities. That way, motorists could find comfortable and relaxing places to stay outwith the busy, noisy and polluted city centres, before completing their journeys for business or leisure into town the following morning. In a British context, this concept represented an expansion and democratisation of the numerous comparatively small ‘roadhouses’ built in similar locations in the 1930s.

For their first such hotel, J. Lyons identified a site by the main London to Bath trunk road (nowadays the A4). At first, a low-rise rectilinear motel, somewhat in the American idiom, was proposed but, between that intention and the hotel being built, the government announced that the adjacent London Airport would be significantly expanded. The airport’s first terminal, the Europa Building, was completed in 1955 (subsequently this became Heathrow Terminal 2).

Responding pragmatically to a dynamic emerging situation in which new modes of transport were quickly usurping domestic rail travel and international sea travel, while possibly reasoning that air passengers, many coming from abroad, would have more spending power than British motorists, J. Lyons decided that, rather than building a motel, they would instead develop Britain’s first dedicated airport hotel. Their site was, after all, right next to London Airport’s main runway. Thus, they waited for three years to begin development work, timing the project’s completion to coincide with the opening of London Airport’s Oceanic Terminal. This was developed specifically to handle long-haul international flights and commissioned in 1961 (nowadays, this is Heathrow Terminal 3).

The new hotel was designed by Philip Russell Diplock and Associates – relatively unknown but prolific designers of a variety of modern commercial building types in the 1950s-80s period. Many of these were dubious in terms of quality and controversial in scale and context but they were far from atypical of much ‘developers’ modernism’ of their period.

Named the Ariel Hotel, Philip Russel Diplock and Associates developed an entirely different plan from the one first proposed for the unbuilt motel. Using a reinforced concrete frame, the building would be four storeys and, unprecedentedly in a British context, circular in plan with a void in the middle. The Architect and Building News explained the rationale behind this in purely functionalist terms; according to their correspondent, it meant that there were relatively few rooms directly exposed to runway noise, yet the design was no doubt also preferred for aesthetic reasons as a low, wide, circular building appeared sleekly dynamic and even futuristic – the perfect aesthetic to reflect the modernity of the jet age to potential users. In plan, public rooms were arranged round the ground floor, where there was a central ‘courtyard garden’, well isolated acoustically from the noise of the airport runway. The entrance foyer had automatic sliding plate glass doors, facing a curving feature staircase with a small ‘water feature’ beneath and the lifts and reception desk on either side with a further plate glass wall overlooking the courtyard garden. Such transparency – engendering a heightened sense of spaciousness and clean lines through the extensive use of frameless plate glass partitions – echoed the latest international design practice. The restaurant and bar were rather Scandinavian in tone, both being inevitably fan-shaped spaces with light modern furniture. Above, three storeys contained a total of 185 bedrooms, all with private bathrooms. These were ingeniously arranged with twin and double rooms around the perimeter of the hotel’s ‘doughnut’ plan, a circular corridor and single rooms around the more constricted ‘inner core’, facing the courtyard. The rooms were relatively compact, some having beds which could convert from sofas but, as most would be staying only one night while waiting to catch flights, or for onward travel, these were strictly spaces in which to recuperate and the inclusion of private bathrooms surely was a welcome necessity – especially when attracting a clientele well-versed in the best American standards in this regard.

The Architect and Building News emphasised that the Ariel Hotel’s façade construction was developed for noise abatement purposes and, while the external walls were indeed particularly thick and well insulated, brief mention was also made of the use of white marble around the entrance and white mosaic on the floors above contrasting in Aalto-style with teak window frames. No comment was made on the most important visual feature lending drama to the building – the broad black bands at first floor and roof height, defining the drum and making it appear to float almost effortlessly above the largely glazed ground floor. Functionally, aesthetically and commercially, so far as can be ascertained, the Ariel Hotel was an immediate and enduring success. At some point during the 1980s, the exterior was re-clad with an extra external layer of sound insulation and curtain walling, impairing the original effect of horizontality, but doubtless responding to Heathrow Airport’s becoming busier and noisier twenty-four hours a day. Having passed with the remainder of Strand Hotels to Trusthouses Forte in 1978, the Ariel Hotel eventually became a Holiday Inn, which it remains today. Apart from the staircase in the entrance lobby, little remains of the original design, it long-since having been replaced by subsequent owners’ corporate identities. Nowadays, guests and visitors would need to use considerable imagination to think of the Ariel Hotel as the glamorous early jet age setting it once was.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.