This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

June 2025 - Faris School, Egypt

Courtesy of the The Hassan Fathy Collection, via ArchNet [ A Catalogue of Visual Documents at the Aga Khan Award for Architecture. Bern, Switzerland: The Aga Khan Trust for Culture, 22-23.]

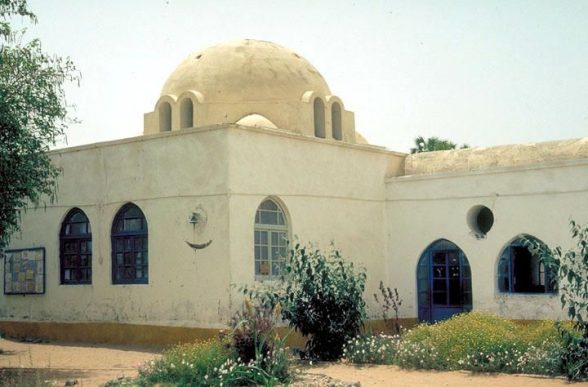

Faris School, Egypt

Hassan Fathy, 1957

Entry by Zaina Abou Seif

What does it mean for architecture to teach – for it to shape shelter so profoundly that it becomes a vessel for belonging, memory, and identity? This question pulses quietly within the adobe walls and cloistered classrooms of Hassan Fathy’s educational complex, nestled in an agrarian village between Aswan and Luxor. Fathy insisted, “A village built by its own inhabitants will grow like a living organism; one imposed by invading professionals will surely die after the builders leave.”

Born in 1900, Fathy (pronounced fat-hee) was a rare figure. The Arab architect, raised in Alexandria, came of age just as modernism was beginning to crystallise into a global language, receiving a European-style education shaped by the movement’s early momentum – the sleek formalities of Beaux-Arts training likely still mingled with the promises of mechanisation, modularity, and the universality of the International Style. He moved fluidly through the intellectual circles of his cosmopolitan generation, even briefly moving to Athens to work under the mentorship of Greek planner Constantinos Doxiadis. It was here Fathy encountered ekistics, the so-called “science” of human settlement, which sought to manage populations as data points within a legible, systemic order. Fathy later critiqued the concept’s inability to fully accommodate the intricacies of non-Western, non-urban life.

Courtesy of the The Hassan Fathy Collection, via ArchNet [ A Catalogue of Visual Documents at the Aga Khan Award for Architecture. Bern, Switzerland: The Aga Khan Trust for Culture, 22-23.]

Disillusioned with the academic classicism he had absorbed, Fathy began grappling with what it truly meant for Egypt to recover its “self” in the shadow of colonialism. Fathy lectured widely in Arabic, French, and English; published articles and essays that articulated his evolving critique of a Euro-centric modernism; and most crucially, led his students beyond the classroom into the villages and ancient archaeological sites of Upper Egypt. Fathy would encounter traditional Nubian aesthetics and building techniques that had endured for centuries, shaped by necessity, and deeply acclimated to environment.

The architect’s increasing interest in Egypt’s built heritage coincided with a period of rapid urbanisation under Nasser’s socialist-nationalist regime, which, despite its anti-colonial rhetoric, turned to Euro-American models of steel and concrete as emblems of national progress. The metropolitan core transformed into a testing ground for these imported forms, but for rural Egyptians who began to disappear from official discourse, these were alien to their socio-ecological realities. Industrial modernity was, to Fathy, a catastrophe that he likened to “cultural murder” – a methodical severing of people from their collective histories, materials, and identities. He came to recognise that these village structures carried a kind of intelligence that challenged everything he had been taught.

Courtesy of the The Hassan Fathy Collection, via ArchNet [ A Catalogue of Visual Documents at the Aga Khan Award for Architecture. Bern, Switzerland: The Aga Khan Trust for Culture, 22-23.]

This is the basis of Fathy’s counterproject: a radically alternative architectural ethic rooted in a deliberate effort to reassert the legitimacy of indigenous knowledge. Fathy began incorporating vernacular elements into his work early on, firstly with his 1942 Hamed Said house, and later, more comprehensively in the New Gourna village of 1945. Domestically, the project caught the Ministry of Education’s attention, who then invited him to design more schools across Egypt. Now straddling the line between government patronage and village allegiance, Fathy aligned with the villagers. He navigated his position to advocate for a replicable, low-cost school model responsive to the cultural and spatial specificities of rural communities.

As an experimental venture, Faris was among his earliest such responses, turning to a collaborative, site-specific endeavour where architecture itself became pedagogical. Constructed for just E£6,000 (roughly £180,000 today), the project was developed to be within reach of the “penniless”. Working with locals to build the school, he and his team provided tools and technical guidance. This was, in essence, an ‘architecture without architects.’ Fathy was steadfast in his belief that the architect’s first task is to listen – to trust the intelligence of place, and invite communities into the act of reclaiming their environments with dignity and care through participatory design.

Courtesy of the The Hassan Fathy Collection, via ArchNet [ A Catalogue of Visual Documents at the Aga Khan Award for Architecture. Bern, Switzerland: The Aga Khan Trust for Culture, 22-23.]

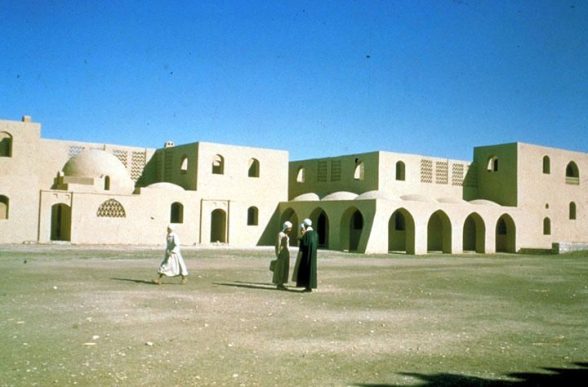

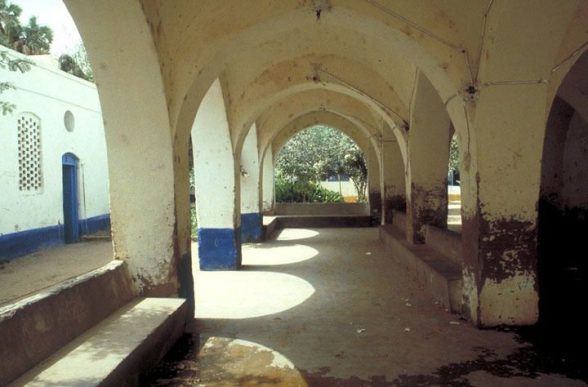

Architecturally, the school reveals itself with delicate confidence, its vaulted volumes rising softly behind a low perimeter wall, as if drawn from the earth itself. A modest entrance portico reconciles the shift from public street to intimate interior, offering both protection and welcome. Within, students move through a carefully staged sequence of thresholds – a choreography scaled to the pace of childhood, gently unfolding across interlocking wings that wrap in a U-shaped embrace around a sunlit central courtyard. This open-air nucleus, drawing from Islamic-Nubian spatial tradition, is a porous heart that mediates circulation, nurtures social life, and invites play.

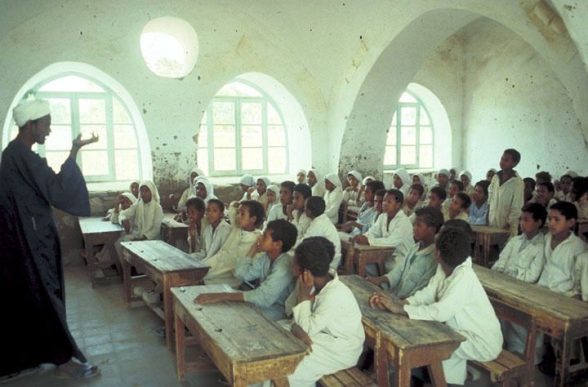

Flanking its edges, two parallel corridors enfold nine classrooms– each a square hall, or qa’ah, crowned by a soaring dome. Around this permeable frame, flora performs in tandem with the smooth brick surfaces: trees cast speckled shade, modulate heat, and trace space with their organic geometries. Fathy intentionally entwined nature and architecture, even calling on the gardener to stitch flowering bushes and walkways between room clusters. As he reflected in Architecture for the Poor, “every square foot, roofed or open, should contribute meaning to the whole.”

Courtesy of the The Hassan Fathy Collection, via ArchNet [ A Catalogue of Visual Documents at the Aga Khan Award for Architecture. Bern, Switzerland: The Aga Khan Trust for Culture, 22-23.]

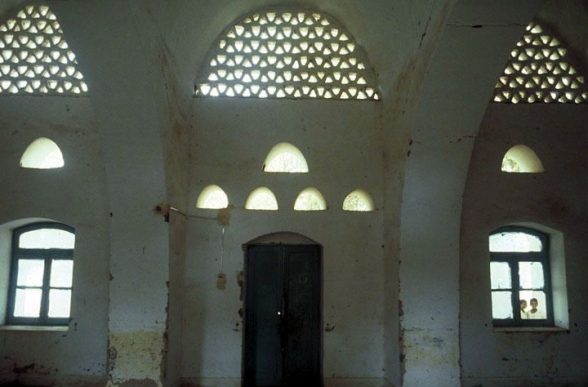

Beyond the classrooms, a library and arts workshop extend opportunities for exploration and creativity, while administrative offices and teachers’ apartments settle discreetly within the plan. Nearby, a multipurpose hall and open-air theatre encourage communal gathering, inviting performance and celebration. A mosque, subtly breaking the rectilinear rhythm, is oriented toward the direction of prayer and holds a hand-carved mihrab to anchor daily ritual. Faris’ decorative program leans on the sculptural appeal of form itself, turning to the interplay of rigid and curving walls, undulating rooflines, and thoughtfully placed lightwells that sculpt shadows.

Within the whitewashed surfaces, bright-blue casement windows and small circular openings punctuate the domes like glowing puzzle pieces. They scatter soft, glistening daylight across the vaults, animating each room with a twinkling, playful luminosity – a reminder that this is, above all, a space for children. When colour appears – ochre doorframes, cobalt paint decals – it almost gestures toward the flowing Nile and the sandy desert, grounding the school as a delicate microcosm of the wider land, a wearable expression of place and possibility. These moments of sensory delight invite us to see architecture through imaginative youthful eyes, alive with whimsy and discovery.

Courtesy of the The Hassan Fathy Collection, via ArchNet [ A Catalogue of Visual Documents at the Aga Khan Award for Architecture. Bern, Switzerland: The Aga Khan Trust for Culture, 22-23.]

That the school still functions decades later is no anomaly. It endures precisely because it was built to belong to its people, and its climate. Long before ‘sustainability’ became doctrine, Fathy pioneered a rigorously intentional low-tech environmentalism that suited the harsh desert heat without relying on energy-intensive methods. Each classroom adjoins a vaulted arcade that rises into a mal’qaf – a slanted wind-catching tower borrowed from Pharaonic precedent, angled to intercept prevailing winds and channel them indoors. These drafts were designed to then pass over shallow salsabil basins, evaporatively cooling the air before it entered the qa’ah – though in practice, some basins were later adapted for additional seating. High-set ventilation slots in the curved ceilings then circulate this refreshed breeze, while warmer air rises and escapes through the mal’qaf’s upper openings, completing a natural convection loop. The thick earthen walls, too, further moderate temperature by absorbing heat by day and releasing it slowly at night. Together, these elements compose a passive, self-regulating microclimate – an elegant orchestration of architectural form and climatic logic.

Fathy’s influence has stretched beyond Egypt, shaping heritage initiatives in Canada, consulting in Iraq and Pakistan, and inspiring sustainable practices as far afield as New Mexico. While often labelled a “traditionalist,” Fathy’s methodology is unmistakably modern – in its ethical stance, sensitivity to contemporary conditions, and its refusal to sever innovation from cultural continuity. An architect who learned to unlearn the boundaries of modernity, Fathy created a built environment where education unfolds not only in classrooms, but through the very act of building.

Zaina Abou Seif is a Masters’ student in Architectural History at UCL Bartlett, with a background in architecture and art history from the University of Toronto. Her email is z.zabouseif@gmail.com

Building of the Month is edited by Joe Mathieson; an Architectural Adviser at the Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust, writer and C20 volunteer.

For pitches, or to discuss ideas for entries, please contact: joe@c20society.org.uk

Courtesy of the The Hassan Fathy Collection, via ArchNet [ A Catalogue of Visual Documents at the Aga Khan Award for Architecture. Bern, Switzerland: The Aga Khan Trust for Culture, 22-23.]

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.