This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

February 2024 - Fischer House, Grundlsee, Austria

Image: © Emilian Hinteregger

Fischer House, Grundlsee, Austria (1978)

Konrad Frey and Florian Beigel

By Sophia Walk

‘Not a Lederhosen (leather pants) house, but a Japanese tea house’, was the brief given by Jutta and Wolfgang Fischer to Konrad Frey and Florian Beigel for their holiday home on Grundlsee, in Austria’s Ausseerland. The Austrian clients and the architects had met in London, where the two art dealers had commissioned Frey and Beigel’s office Building, Planning & Resources (which existed from 1970 to 1975) to design the exhibition space for their gallery Fischer Fine Art in 1971. The Fischers wanted a holiday home in their home region for themselves and their growing family. They did not have a house in the traditional architectural style of the Styrian Salzkammergut in mind, but rather saw a reference in the architecture they had encountered while travelling abroad, especially in Scandinavia and Japan.

Image: © Emilian Hinteregger

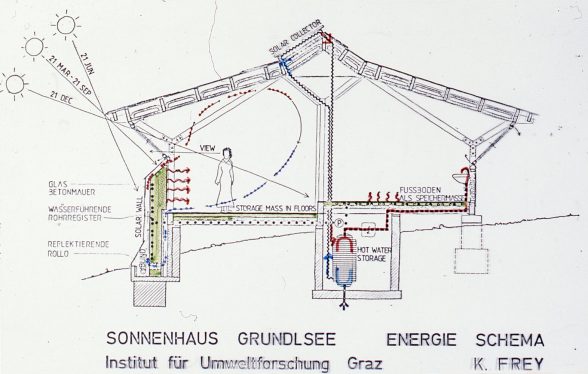

The Fischers’ summer house was planned from 1972 and completed in 1978. It is the first solar house in Austria and thus characterised by its experimental character of using solar energy. ‘At the beginning of the 1970s […] we were concerned with the energy problem. We gradually realised how little care we were taking with this limited resource. And we started to think about whether it would be possible to build houses that were designed to consume much less energy,’ explained Frey at the house’s inauguration. The façade on the south side is designed as a ‘Trombe wall’, named after the engineer Félix Trombe, developer of the system in the 1960s. The wall is made of black heavy concrete at up to 40 centimetres thick, and over 28 square meters. It absorbs the sun’s heat through the single glazing in front of it, stores it and then emits it inwards. Four heat sources supply the house: the solar heating, the traditional tiled stove heating, the underfloor heating and the retrofitted electric central heating.

Frey and Beigel relate both the house to the landscape, and the landscape to the house. On the one hand, the slope of the plot is incorporated into the architecture. Two steps each separate the access zone from the south-facing living rooms, thus not only ensuring that the house nestles against the slope, but also structuring the living spaces. On the other hand, the predominant use of wood as a building material is a typical element of Ausseerland architecture. Looking upwards in the house is like looking into the crown of a tree. The dominant roof can bear heavy snow loads and is supported by tree-like pillars that expand into branches and form a spatial supporting structure.

Image: © Emilian Hinteregger

Differently sized windows act like frames that open up views of the landscape. To the north, the mountain massif of the Totes Gebirge; to the east, the surrounding trees; and to the south, Lake Grundlsee. Where any other architect would have planned a large panoramic window facing south, Frey and Beigel only placed the small framed views. This decision has a lot to do with the solar concept – letting in the low sun in winter and keeping out the high sun in summer. But it also has to do with the view of the landscape, which you otherwise become blind to if you constantly enjoy it in large doses.

The living floor plan, with its usable area of 120m2, testifies to Frey’s deep understanding of the residents and their everyday lives. This can be seen in unpretentious solutions such as the handrail or the bookshelf, which follows the spatial structure of the house. His deep understanding is also evident in the way he translates the movements within a room, between the rooms, within the house and where the house, as Frey says, ‘frays into architecture’, creating slow transitions from the inside to the outside.

Image: © Emilian Hinteregger

A sun house in Frey’s sense also considers the orientation of the house on the plot, the arrangement of the rooms in the house, the distribution of functions, the careful coordination of building mass and glazing and their effects on the respective functions of the rooms. For Frey, the sun and its influence on the lighting and heating of the rooms were always decisive for all these decisions. This can also be seen in the fact that the users of Frey’s buildings move inside and outside the house with the sun. This is most evident in the use of the terraces. Austrian architect and architecture critic Friedrich Achleitner sees the house as ‘probably the most natural response to the climate of the Styrian Salzkammergut.’

Critical voices from back then have long since died away. ‘Game feeding’ was the most harmless term the Grundlsee residents found for this house. The owners themselves spoke of a swallow, which they recognised in the external shape of the house, and whose small extension to the west of the entrance looked like a swallow’s tail. In this sense, some contemporary critics categorised Haus Fischer as belonging to the expressionist branch of the ‘Graz School’, or alternatively ‘organic architecture’. It has even been described as mannerist.

Image: © Emilian Hinteregger

For Frey and Beigel, however, the appearance and thus the architectural solutions were focused on functional aspects and the idea of a solar house. Even today, Frey says in retrospect that Haus Fischer was not the result of formal considerations; this type of design was not his or Beigel’s style. In contrast, Peter Blundell Jones sees the design as a symbiosis of functionality and organicism. Even if the solar experiment was a partial failure, the way in which Frey and Beigel used innovative architectural means to utilize solar energy and at the same time responded to the local context is what makes this pioneering building so special. Today it is one of the most important and independent examples of Austrian architecture in the 1970s.

Critical catalogue: https://konradfrey.tugraz.at/

Sophia Walk (@walk_sophia) is an architectural theorist. She has researched and taught at the Institute of Architectural Theory, Art History and Cultural Studies at TU Graz, the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, KIT Karlsruhe, and currently at Leibniz University Hannover.

Credit: Archive TU Graz.tif

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.