This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

August 2025 - General Sciences Library, Vietnam

Image credit: Alexandra van der Essen

Bùi Quang Hanh and Nguyễn Hữu Thiện, 1971

Nested within a torrent of motorbikes flooding through the centre of Ho Chi Minh City sits an urban modernist oasis, the General Science Library. The building exemplifies the overlooked architectural movement of Southern Vietnamese modernism.

Few realize that Southern Vietnam holds one of the world’s largest concentrations of mid-century modernist buildings. After the end of the Indochina Wars in 1954, modernism emerged as the dominant reconstruction style – a post-colonial statement of progress that ultimately shaped more than 60% of urban homes. To cope with Southeast Asia’s tropical climate, architects designed an array of elements (brise soleils, pergolas, louvres, sunscreens) for shading and airflow. Unlike the heavy, monolithic forms of global modernism, these elements were crafted to be distinctively light and delicate. Together they formed an architectural vocabulary, an ‘alphabet’ that could be combined in infinite variations, resulting in façades more complex – and even decorative – than their international counterparts.

Seeing modernism as a symbol of progress and independence, the public adopted these elements and made it their own, so completely that it evolved into a new vernacular. Nowhere does modernism permeate everyday homes as vividly as in Southern Vietnam. This vernacular modernism also shaped institutional buildings, with the General Science Library standing as an elegant testament to this overlooked architectural legacy.

Inaugurated in 1971, the library was designed by architects Bùi Quang Hanh and Nguyễn Hữu Thiện, whose contrasting backgrounds would prove complementary. Bùi Quang Hanh brought an international perspective: he studied at the National College of Fine Arts and the Urban Institute at the University of Paris and practiced professionally in the United States before returning to Vietnam, where he designed numerous educational buildings. Nguyễn Hữu Thiện, meanwhile, graduated from Hanoi’s Indochina Fine Arts College and specialized in temple design. Their collaboration resulted in a balanced combination of traditional and modern forms.

Image credit: Alexandra van der Essen

The site of the library itself carries deep historical weight: it once housed the Maison Centrale de Saigon, a French colonial prison notorious for overcrowding, epidemics, and executions. Among those held there was the young revolutionary Lý Tự Trọng, executed at age 17, whose name now marks the street outside. Despite this sombre past, the library radiates quiet harmony, serving as a popular breathing space for locals amid Ho Chi Minh’s hyper-dense urban fabric.

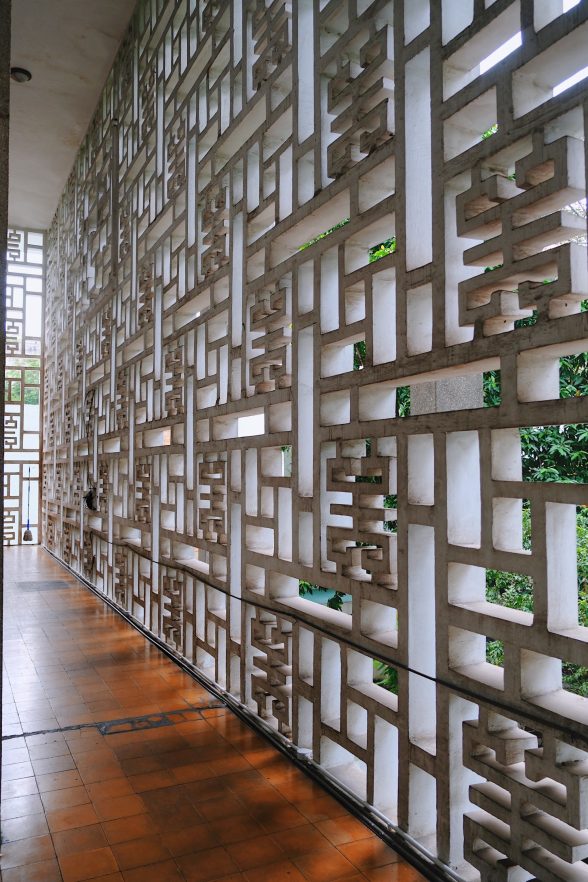

From a design perspective, the library exemplifies the intricate detailing and climatic intelligence characteristic of Southern Vietnamese modernism. As visitors walk through the entrance gate, they are immediately struck by the giant white geometric brise-soleil (sun-breaker) covering almost the entire façade. Both functional and decorative, this concrete screen deflects the intense afternoon sun, naturally regulating the interior temperature for readers. Forming a double wall, it facilitates air circulation and provides ample canopy to shield from rain. Beyond its impressive size, this brise-soleil also stands out for its complex, lace-like patterns. Repetitive geometric forms are gracefully woven together with stylized motifs drawn from Chinese calligraphy. Phạm Phú Vinh, Vietnamese architect and author of Poetic Significance: Sài Gòn Mid-Century Modernist Architecture, describes the library as being ‘wrapped around by a curtain’, its surface so large that it becomes a kind of fabric. The delicate concrete detailing, interspersed with touches of enamelled mosaic elsewhere on the façade, produces constantly shifting patterns of light, like shimmering embroidery on fabric.

Image credit: Alexandra van der Essen

Walking further into the library garden, visitors encounter another clever climate-responsive feature: a shallow pool inspired by phong thủy, the Vietnamese adaptation of feng shui. This water corridor functions as natural air-conditioning, cooling the air that passes before it enters the reading rooms. As American architect Mel Schenck writes in his book Southern Vietnamese Modernist Architecture: ‘this building is at the forefront of environmental or green design.’

Southern Vietnamese modernism typically leans towards abstraction, avoiding overt traditional symbols. The General Science Library is an exception. Dragons and phoenixes – mythological creatures believed to bring harmony and positive energy – are artfully integrated with Chinese characters for happiness. This conspicuous symbolic experimentation was deliberate, part of a collective Vietnamese effort to reconnect with cultural heritage disrupted under colonial rule. Many public and administrative buildings of that period incorporated traditional symbols to celebrate local craftsmanship and reinforce national identity. Architect Lê Văn Lắm, who served as a technical advisor to the project, clearly expressed this vision in 1967: ‘The Library must be regarded as an important architectural landmark – solid, enduring, and beautiful – worthy of being a treasure of the Capital. In the context of an independent nation, it is essential to promote national culture to mark a renaissance. Architecture should be studied with Vietnamese lines, […] both exterior and interior, must be designed and decorated in the Vietnamese spirit.’

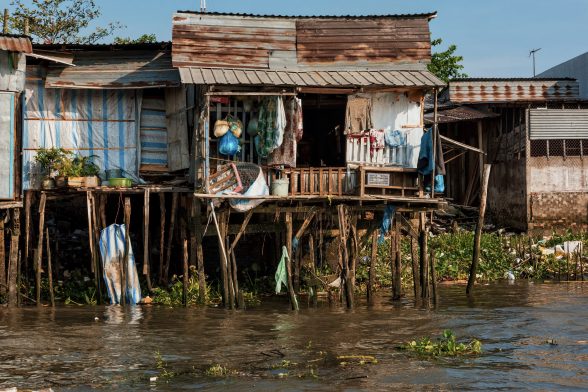

The library’s outer structure also honours vernacular architecture. Its front columns descending directly into the water subtly evoke Mekong Delta stilt houses designed to withstand seasonal floods. Above, a thick, flat roof with gently up-curved eaves rests on exposed beams, reminiscent of traditional communal houses (Đình). This influence is unmistakable – not only in structure but also in spirit, as Đình have long served as gathering places for village communities.

The General Science Library captures the essence of Southern Vietnamese modernism: a refined distillation of modernist rationality and Vietnamese spirituality. While international modernism favours technical decisions, its Southern Vietnamese version stands out by seamlessly blending decoration with functionality. Each element – brise soleil, pergola, louvre – begins with a practical purpose, but is elevated into an artistic composition. This tendency towards decoration became even more pronounced as this architectural language was adopted by ordinary homeowners. Phạm Phú Vinh wrote these elements are ‘carefully put together not for any particular purposes other than a sensuous satisfaction of richness and excitement that was to be contemplated. These expressions are a reflection of the innate sense of aesthetics of Vietnamese culture’.

Alexandra van der Essen is an architecture photographer and writer from Belgium (Instagram: @cleopatella, website: cleopatella.com)

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.