This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

© Tom Parnell

August 2021 - Irvine Centre, Irvine, North Ayrshire

Irvine Development Corporation (1973-75)

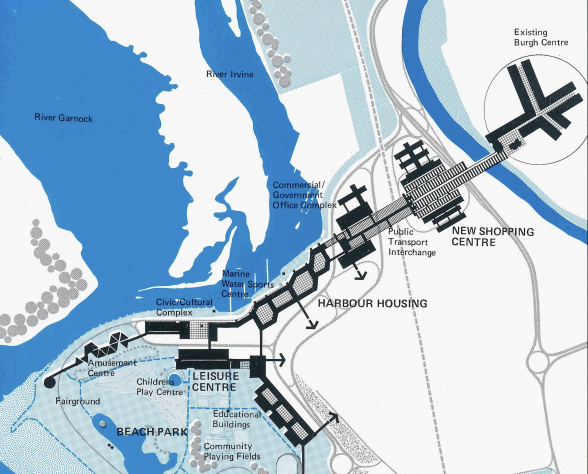

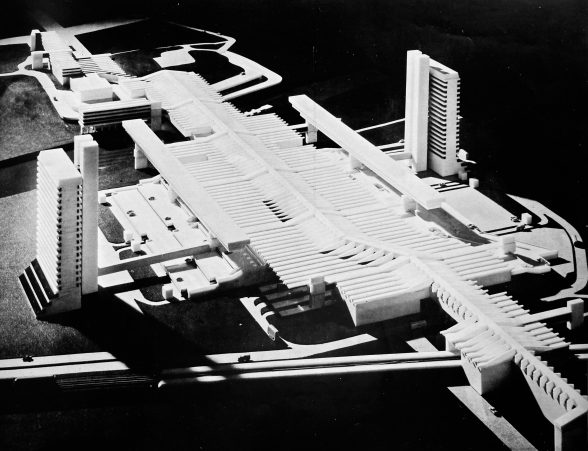

At 1.5km long the Irvine Centre, when completed, would have been visible from orbit. Conceived as the megastructural centrepiece to Scotland’s fifth post-war New Town, the vital statistics for this enormous building are impressive today but, at its conception in 1969, they must have been almost incomprehensible: fully-enclosed, climate-controlled shopping malls totalling 450,000 square feet; multi-storey parking for 3,500 cars; tower blocks of apartments and offices; a leisure centre; civic centre; conference centre; cinema; bus station; rail station; hotels; public squares; restaurants; cafes; bars. When the building opened in 1975, Irvine was a small town of little more than 35,000 people. How did this huge monolith from the future come to be grafted on to a quiet medieval burgh on the west coast of Scotland?

In 1966, Irvine became the largest New Town in Britain (until it was eclipsed a year later by the movement’s zenith, Milton Keynes). In a clear nod to the unrealised plan for Hook, an outline scheme by Hugh Wilson, of Cumbernauld fame, called for a town centre capping a river valley to the east of Irvine. This was quickly abandoned however by Irvine Development Corporation (IDC) after disused mines were discovered. Chief architect David Gosling and town centre group principal architect Barry Maitland, both alumni of Runcorn New Town, frantically began seeking alternatives, eventually turning to Irvine burgh itself.

© North Ayrshire Council

The solution was found to the west, in a low-lying loop of the River Irvine between the burgh and the harbour. Mac Dunlop, IDC architect and local Irvine lad, saw an opportunity: ‘this area of ground across the river, Friar’s Croft, had been cleared by the burgh [council]. There were lots of really old buildings over there.’ Dunlop envisioned the new centre resembling Runcorn’s megastructure, Shopping City, ‘as a totally heated and enclosed multi-building’. Helmed by Gosling, Shopping City had been laid out on a super-grid capable of expansion in all four cardinal directions. Friar’s Croft offered a more constrictive site however, and the Irvine Centre soon took on a linear form growing west from the existing town.

Hook and Cumbernauld were acknowledged as inspirations, with the building conceived as an attempt to develop ideas from those centres into an urban structure that continued the traditional street as a fully enclosed and indoor space, rather than as separate structures. Kenzo Tange’s metabolist dreams for Tokyo Bay were another strong influence; Tange advocated a move away from radially structured towns and cities to vertebrate-like linear structures. The ‘street’ of the new Irvine Centre was to run beneath a ‘spine’ carrying services, out of which spread ‘rib ducts’ for tenant servicing. Deeper, at ground level, was a cavernous circulatory system of one-way roads, plant rooms, and storage areas — the centre’s vital organs.

© North Ayrshire Council

Echoing Runcorn and Hook, the centre sprung out from the high ground of the burgh to connect with the elevated railway beyond Friar’s Croft, allowing for a seamless pedestrian walkway between historic town and station. The Magnum, then the largest leisure centre in Europe, was built in the town’s harbourside to help stimulate the eventual stitching up of this linear titan.

‘We were thinking of — still going at high level — we had to go over or under the railway station,’ said Dunlop, ‘and going down to the Magnum, and coming in its gable. That’s why the Magnum is a linear concept.’

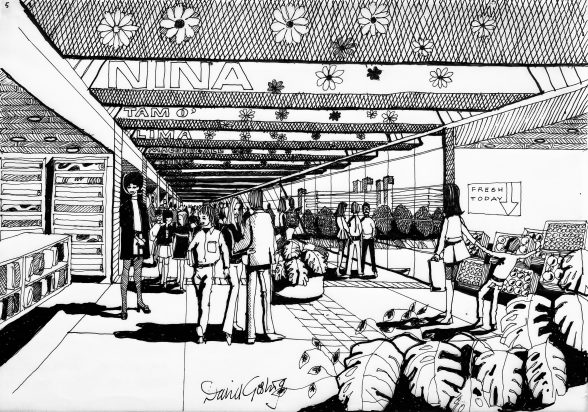

When Phase 1 opened, the Irvine Centre became the only one of its kind — indeed, one of only a handful of buildings in existence — to span a river. Brightly lit, heated, ventilated, and ultimately air-conditioned, it was state-of-the-art, even experimental. Building regulations were entirely unequipped to deal with a structure of such unorthodox size and function and had to be relaxed by the government. The finishes reflected the changing topography, with dark brown brickwork ‘below-ground’ and white stove-enamelled aluminium panels ‘above’, an effect mirrored in the Magnum to reflect the anticipated coalescence. Inside, a deeply profiled ceiling, pierced by clerestories, expressed the ribbed form of the roof. Flooded with natural light, the mall was adorned with floor and ceiling planters and chunky, vibrant, furniture designed by the Corporation. Phase 1 contained 50 shop units totalling 250,000 square feet and 1,200 parking spaces.

© North Ayrshire Council

Like so many megastructures, the Irvine Centre was never completed. Even before it opened, Gosling, Maitland, and Dunlop had all left IDC. However, where Cumbernauld’s concrete chimera has seen an erosive, perverse inversion of its compact, segregated indoor centre into a largely empty hulk besieged by retail sheds and seas of parking, the Irvine Centre has not suffered such a twisted fate. Fragmentary it may be — the Magnum was demolished in 2017; the adjacent office blocks, also intended to connect with the building, have since seen re-cladding efforts that vary from the anodyne to the incongruous; the temporary western elevation now bears a clumsily integrated supermarket — but beneath a boxy replacement roof (which blocked the clerestories) and a smattering of Po-Mo embellishments which muddy IDC’s uncompromising aesthetic, Phase 1 survives intact.

The flexibility in the original design can be readily discerned, too. Outside and in, the centre is riddled with dead-ends. Floating corridors sprout optimistically into thin air and future apertures remain plugged, as though the building’s metamorphosis has yet to take place. All over the Irvine Centre shouts proudly its unfinished state and its flexible ideals. Writing in the August 1976 Architects’ Journal, Keith Smith, deputy chief architect at Runcorn, noted ‘the primary service ducts, poised ready to strike their way over the next phase, eloquently express the very essence of the megastructure concept’. However, the design’s failings as a result of the unbuilt later phases are readily apparent; the building never reached the rail station, ironically necessitating a navigation of roads and car parks that it sought to overcome.

© North Ayrshire Council

It is not a pretty or subtle building (Smith carefully noted it ‘presents a considerable visual surprise’). Manifesting a factory-like modernism in its throes, the Irvine Centre is brutalist in both material and connotation, and metabolist not only in the hints of unfinished growth but in its blatant digestion of what came before; IDC are vilified in Irvine for the perceived devastation it wrought. Local zealotry aside, ‘the Mall’ (as it is known to Irvinites) survives with all the thrust and swagger its architects intended, a prototype shopping and entertainment complex, a leviathan from a failed future.

© North Ayrshire Council

© Joss Durnan

What will become of the avant-garde ‘enclosed multi-building’? The Irvine Centre ranks among the few megastructures that, in their stunted forms, ever made it off the drawing board. Many developments that channelled similar thinking have been demolished. Others — Preston Bus Station, Unités d’Habitation, the Barbican — have become tourist attractions, filming locations, pieces of cultural heritage in their own right. For Geoffrey Copcutt’s defiled Cumbernauld vision, the wrecking ball looms. But at Irvine, Gosling’s utopian chiaroscuro of leafy light on concrete survives, beating beneath, waiting to be resuscitated.

Joss Durnan (@joss_durnan) is an archaeologist and architectural historian based in Edinburgh. His book chronicling the history of Irvine New Town will be submitted to publishers in 2022. Irvine will feature in episode 1 of ‘The Years That Changed Modern Scotland’ on BBC Scotland, Sunday 8 August, at 9 p.m.

The Building of the Month is edited by Dr. Joshua Mardell.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.