This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

January 2022 - Kensal House, West London

(Flats Municipal and Private Enterprise, Ascot Gas Water Heaters Ltd, 1937)

Kensal House, Ladbroke Grove – Elizabeth Denby and E. Maxwell Fry (1936)

Grade 2* listed Kensal House began life as a decision made in 1933 by the Gas, Light and Coke Company (GLCC), one of London’s major public utility societies, to build a block of flats for its workers on the site of a disused gasholder at the top of Ladbroke Grove, west London. By the time it was completed in late 1936, it had become much more and constituted a definitive statement of all that social housing in the period could and should be.

That this would be the case was largely because of the involvement of two particular members of the advisory committee the Company retained. Comprising architects and a housing consultant, this had been appointed as part of the gas industry’s plans to modernize its organisations and its product ranges in the face of competition from the more evidently up-to-date electricity industry. For the most part the committee advised or designed products and the showrooms that displayed them, but the commission for a block of flats was a rather different beast and that prize job went to the housing consultant, Elizabeth Denby (1894-1965), and the rising young star of English modernism, Max Fry (1899-1987).

There is no definitive evidence that explains the choice to appoint these two figures but Fry was the most progressive of the architects on the committee, while Denby was already well-known to the Company for her work for a local housing association (Kensington Housing Trust) and her expertise in social housing and was, at this date, just embarking on her career as a housing expert. Denby and Fry managed to convince the Company to give them free rein, and in their hands it became an exercise in model housing both programmatically, technologically and materially and a demonstration of how to design in the most modern of ways.

(Kensal House, A Contribution to the New London, Capitol Housing Association, 1937)

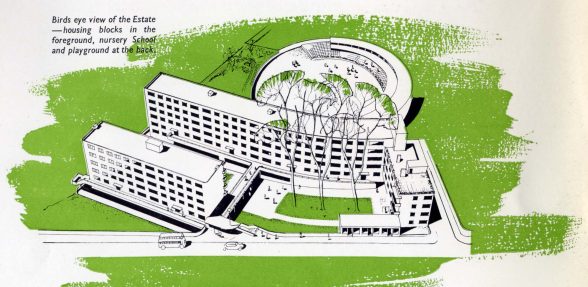

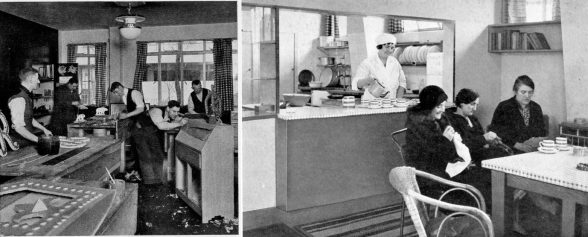

Denby and Fry realised that if the GLCC were to form a housing association, it could apply for government subsidies to fund the building. The Capitol Housing Association was duly formed and the flats then became the opportunity to show what could be done with the same subsidies used for local authority housing. The next step was to recruit advisers from other progressive spheres in order to draw up a programme that would make the scheme, as a journalist later wrote, “the last word in working-class flats.” The landscape architect and nursery school advocate Marjory Allen came on board as did Freda Dudley Ward, whose Feathers Club project, which built clubs for unemployed men in slum areas, was backed by her lover the Prince of Wales. Research was undertaken into how best to exploit concrete technology and the most efficient ways to heat and equip the blocks. The result was an estate that harnessed to technology to social ends, and which comprised not just 68 tightly-planned and well-equipped flats, but also social clubs (including a branch of the Feathers Club) in the basements of the main blocks, allotments, a nursery school and a playground.

(Flats Municipal and Private Enterprise, Ascot Gas Water Heaters Ltd, 1937)

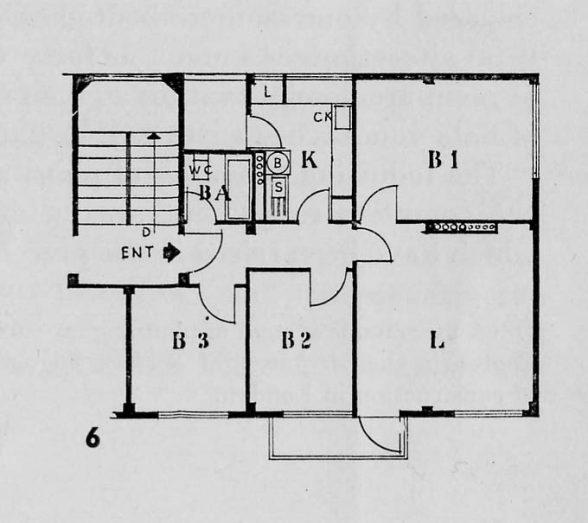

The flats were either two-bedroomed (on the ground floor, with pram sheds taking the space otherwise occupied by a third bedroom) or three bedrooms (floors 1-3). The bathroom and kitchen shared piping to minimize infrastructure costs, and were kept small. One or two bedrooms led off the entrance corridor. The main space was giving to a family living room; its modernist hearth created by a gas heater and radio speaker/receiver above it. The parents’ bedroom was accessed from here (thus, once the children went to bed, they had all the space for themselves). A family balcony opened from the living room – and was wide enough for a chair and table, as well as a seed box for the food that would be grown in the allotments. Tenants had access to the shop Denby had opened with the St Pancras House Improvement Society, House Furnishing Ltd., where they could buy on affordable hire purchase rates, well-designed furniture (including some specially commissioned from Gordon Russell).

For families who had hitherto lived in overcrowded and dilapidated slum housing to move to Kensal House gave the opportunity to re-order their family life; boys and girls could have separate rooms, mum and dad a room and a bed to themselves. The labour-saving design minimized house work and freed up the women of the estate to spend their free time in the social clubs or contribute to what was the most innovative part of an already innovative scheme.

(Council for Art and Industry, The Working-Class Home: Its Furnishing and Equipment. London: HMSO, 1937 – Kensal House, A Contribution to the New London, Capitol Housing Association, 1937)

‘The spirit of the estate is that the tenants run it themselves’, wrote Denby in 1937. The intention was that the tenants would be responsible for the day-to-day running of Kensal House, with Denby acting initially as Housing Director. Each staircase had its own committee, and contributed a representative to a ‘management’ committee. Denby’s experience in housing management made her understand how important a sense of ownership was in social housing; it was also an important exercise in democracy in a decade when totalitarianism was on the rise in Europe and the women residents were new to the vote (given to all women only in 1928). That it worked for the women is evidenced by the fact that in wartime, two Kensal House women went on to serve on the Utility Furniture Advisory Committee (of which Denby was also a member).

Tenants moved in to Kensal House in November 1936; Denby’s friend the recently-qualified architect Mary Crowley was on hand to assist. Formally opened by the Minister of Health in March 1937, Kensal House was widely praised, not just in the architectural press but in the general press. The British Commercial Gas Association made a film about it (it had made its debut as a model in the film “Housing Problems”, 1935) and it featured as a sign of things to come in the campaigns of the National Smoke Abatement Society and in the book Working Class Wives by Margery Spring Rice. In wartime it featured in the poster series for the Army Bureau of Current Affairs ‘Your Britain fight for it now’ – the elegant curve of its balconied façade juxtaposed against the slums it had replaced.

Its post-war history was a little uneven; but it was listed in 1981 and is now recognized as a major step towards an understanding of housing as more than just bricks and mortar.

Dr. Elizabeth Darling is Reader in Architectural History at Oxford Brookes University. She researches gender, sexuality, space and reform in the 1890s–1940s and interwar English modernism. Publications include Re-forming Britain (2007) and Wells Coates (2012) as part of the Twentieth Century Architects series published jointly by RIBA Publishing, English Heritage and the Twentieth Century Society. With Lynne Walker, she curated the exhibition AA XX 100 (2017) which marked the centenary of women’s admission to the Architectural Association; Walker and Darling co-edited the resulting publication, AA Women in Architecture 1917-2017 (2017). @ArchHistDarling

The Building of the Month feature is edited by Dr. Joshua Mardell.

In partnership with The Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.