This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

March 2003 - Meeting House, University of Sussex

Owing to growing secularisation, there was a noticeable shift during the 20th century, from a concern with and design of religious buildings, to that of a concern with civic, cultural, and commercial buildings.

Some exceptions to the above can be cited though: buildings such as Guadi’s Sagrada Familia and Corbusier’s Ronchamp were designed exclusively for the pursuit of spiritual enlightenment. These, however, are unfortunately not on my home turf.

I was, therefore, taken aback by the discovery of a 20th century building of a religious nature on the grounds of the University of Sussex. Furthermore, the building to my complete surprise had a profound impact on me – despite my supposed non-religiosity, and despite my viewing of my built environment, as not being sufficiently rich in the poetic.

The uniqueness of this experience subsequently prompted a series of investigations as to the reasons and ways in which, a specific class of building/s or structure/s can create a heightened sense of place, self, and the ineffable.

A plan to erect a building that would cater for the religious needs of members of the university was included in the original master plan for the Sussex campus. Its construction, however, only became feasible in 1962, through a donation by Sir and Lady Caffyn.

The final 1963 brief for ‘The Meeting House’ emphasised the need to create a non-sectarian place of worship: a place where a “different mood would prevail and where one could…be still and know.” (II.IV.X6 VOS Meeting House, Special Collection, Library of the University of Sussex). This requirement reflected the university’s mixed population, and the wider context of a self-consciously pluralistic civil society. The brief also specified a need for quiet rooms, a place for recitals and meetings, and rooms for the chaplains and the administrative staff.

Basil Spence’s practice was therefore called upon to create a structure, which would centre wholly on the pursuit of spiritual experience, and be able to offer a non-traditional context for an engagement with the ineffable and the spiritual. The findings below will show that the practice’s design met these requirements in a very imaginative way.

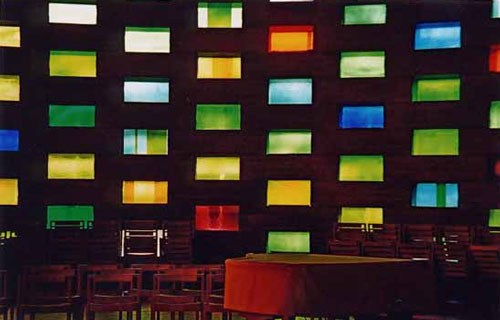

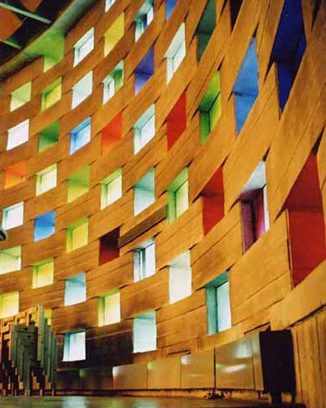

The Meeting House, which was begun in 1965 and completed in 1966, is 80 feet in diameter, and contains a sitting area for 350 people, and is located to the side of the campus’s bridleway. It is made up on the outside form a circular and jigsaw-like skin of coloured glass panes and white rendered concrete, and is size wise unassuming.

Internally, and by contrast, and despite an obvious debt to other contemporary churches on the mainland (most notably Ronchamp By Corbusier 1955), the building is revealed to be a monument of a very special nature.

Inside its intimate internal circular space one benefits from feeling both anchored and safe, and yet is instantaneously enveloped – as a result of the building’s jigsaw skin of coloured glass – with a wondrous interplay of light and colour.

I understood after a period of reflection that my strong reaction to the building was the result of practice’s success in creating a building that would not be about the staging of an experience of transcendence – as that offered in the arts complex opposite, or that offered by use of symbols – but itself be the trigger of such an experience.

The building it could be suggested achieved this goal, through its emphasis on the synthesis of the experiential qualities of the language of art and the language of architecture.

The building employs two distinctive creative languages, that of painting, to which one could argue glass belongs, and that of architecture. Through its fusion of the structural volume defining power of architecture with the potentially elemental, reverie inducing, and ecstatic quality of colour it succeeds in attaining internally a very rare synthesis of these two languages.

The design’s employment of pure colour areas provides the viewer with an opportunity to experience colour in its most elemental and pure form: as a non-tangible, de-materialized presence or force, and as a complete counter to his or hers and the building’s static physical nature.

The boundless and wondrous qualities of light and colour that fill the building’s interior, as the result of its unique skin, are able to transport the viewer into an otherworldly setting. They also serve further to that, as a metaphor about the richness of Creation, as the rainbow and its colours, are said in Genesis to be a symbol of the covenant between Man and God.

The success of the building’s design thus could be said to rest on a full but balanced employment of two languages: one which allows architecture to ‘discharge’ its principle roles in creating concrete extensions of reality, and of materializing the immaterial, and the other, which allows painting its ability to de-materializing the material and that of creating pockets of ‘unreality’.

Unlike the buildings that surround it, the Meeting House not only offers the above unique synthesis, but also through its’ emphasise on a personal dimension of experience, transforms an impersonal space or location into a place. A place which further more is able to provide in a non- sectarian manner a sense of ‘a home – in – the – world’ (J. Bates ‘The song of the Earth’); and which is able to allude to, and be indicative of, a ‘cosmic situation’ (Bachelard ‘The Poetics of Space’).

The Meeting House, which succeeds in emphasizing the experiential dimension of architecture, has not lost to this very date – despite its relative obscurity – its ability to offer a supremely special context for an engagement with the spiritual and the religious. It is further to that is an instance in which art and architecture were and are able to reclaim a highly elusive spiritual role.

© Orna Neumann 2003

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.