This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

Credit: Historic England

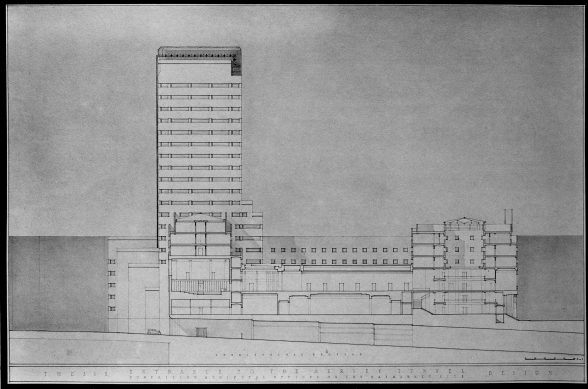

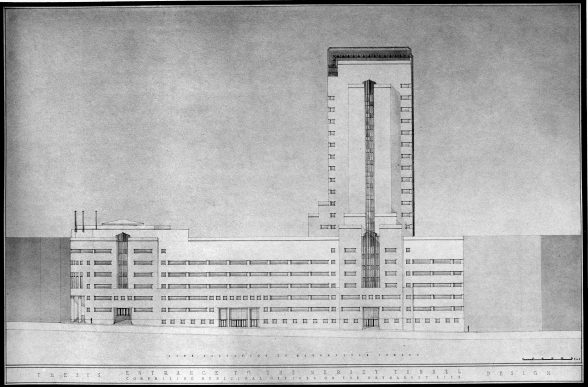

November 2021 - Mersey Tunnel Ventilation Towers

Herbert J. Rowse, 1925-34

Ranking as one of the great municipal achievements of the inter-war years, the Mersey road tunnel was celebrated with pride by both Liverpool and Birkenhead when it was opened by the King George V in 1934. Architect Herbert J. Rowse’s contribution to the later stages of this project included the design and styling of the tunnel interior, entrances and toll booth plazas, as well as the construction of six massive ventilation stations, which became landmarks on both sides of the river.

Credit: Historic England

The most prominent ventilation tower in Liverpool is at George’s Dock, adjacent to the ‘Three Graces’ at the Pierhead, and is perhaps the most sophisticated of this group. It is certainly different, largely windowless but with elegant Art Deco low-relief decoration not only on its ashlar external surfaces but also on many of the interior ones, despite this being, in reality, an industrial building. However, the site constraints presented Rowse with a complex design problem. With its intake and extract tower, tunnel control room and offices of the future Joint Tunnel Company forming a base, the structure had been squeezed onto a surprisingly restricted site. It needed to sit beside (rather than directly above) the tunnel, which ran beneath the road separating the Harbour Board and Cunard Building, while avoiding an old infilled-dock that could not be excessively loaded. Hence the two gardens flanking Rowse’s building and the promise that they would be maintained as landscaped open space.

Credit: Liverpool University Special Collections

The decoration of the Pierhead tower was lavish. The George’s Dock Way frontage contains a large carved relief, designed by Rowse and executed by Thompson and Capstick, entitled ‘Speed’. It consists of an extremely stylised tall streamlined figure that is symmetrical along its vertical axis. Apart from the head, which is wearing a motor-racing helmet and raised goggles, all human characteristics are eliminated in order to emphasise the vertical lines – presenting an image of motorised speed. The tower is also adorned with a number of other sculptural reliefs and free-standing sculptures. ‘Night’ and ‘Day’, both by Thompson in black basalt, are intended to convey the ‘always open’ nature of the tunnel. In addition, there are four large reliefs, one on each of the building’s façades representing ‘Civil Engineering’, ‘Construction’, ‘Architecture’ and ‘Decoration’ – together with a repeated relief on all four façades entitled ‘Ventilation’ that consists of a symmetrical design based on a ventilator shaft blowing out vitiated air, represented by a stylised Art Deco-inspired zigzag pattern. There’s certainly a flavour of the 1929 Hungarian pavilion by Dénes György and Nikolaus Menyhért that Rowse saw when he visited Barcelona and purchased the Exposición Internacional de Barcelona catalogue.

Credit: Liverpool University Special Collections

Unlike the other five ventilation buildings, which share the same ‘turret’ motif while occupying unique bases, the Birkenhead Woodside tower presents a new variation due to its close proximity to the river. This slender masonry structure, located just 5.7m from the river wall and on a very restricted site, forced a dramatic tower solution, offering a formidable outline at 65m tall, and highly visible when viewed from across the river. The symmetry found in all the designs was due to the internal arrangement of the fan machinery, installed in duplicate should any of the components break down. Located alongside the fans are two shafts delivering intake and exhaust air, which of course, had to be kept separate, the exhaust not contaminating the inlet and discharging at an appropriate distance from surrounding buildings. The machinery is supported on a steel frame, which also provides the main structure for the façades. Woodside again caused considerable difficulty as so much of the interior volume had to be kept clear of ‘structure’ to enable the fans and ducts to be installed, coupled with the extreme loads placed on a building of this height. A solution was found by casting concrete stanchions in each corner of the structure taken down 12m to bedrock. The brickwork, laid with flush mortar joints, gives a bold monolithic impression, with vast surfaces left plain. At the corners and cornices, the bricks are laid in bands of proud, recessed and edge-on courses to form discrete but very effective patterns in a monochromatic palette.

The ventilation structures are all so carefully composed that it is easy to forget they are the casements for functioning machines. Frederic Towndrow went even further, imbuing them as living things, ‘like huge animals, breathing out at the top and breathing-in just below the top … there is nothing like them in the world’, indeed they sit, silently, and seemingly without any human interaction ensuring a subterranean existence below.

Credit: Historic England

Iain Jackson is an architect and lecturer at the Liverpool School of Architecture. He is the author, with Simon Pepper and Peter Richmond, of Herbert Rowse for the C20 Society’s Twentieth Century Architects series available here. The Building of the Month feature is edited by Dr Joshua Mardell.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.