This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

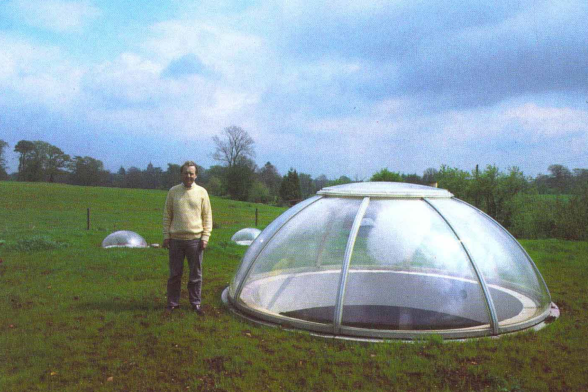

April 2025 - Mole Manor, Westonbirt

Image credit: George Perkin, Concrete Quarterly

Mole Manor, Westonbirt, Gloucestershire (1982-87)

Arthur Quarmby

In 1980, Stuart Bexon, a marketing consultant, had his proposal to build a new house in the garden of his Gloucestershire home refused by the local authority. When Bexon discovered that nuclear bunkers did not require planning permission, he began investigating the idea of building his house underground. Although it transpired that permission would still be required, Bexon’s plans for a partially buried, four-bedroom house on the site won the planners over and he was given consent in December 1983.

The design for the house, affectionately known as Mole Manor, was drawn up by the Huddersfield-based architect Arthur Quarmby (1934-2020). Quarmby was well suited to the task, as he was the long-time president of the British Earth Sheltering Association and had designed Underhill, the first modern earth-sheltered house in Britain, as his family home (Grade II listed in 2017 thank to an application by C20).

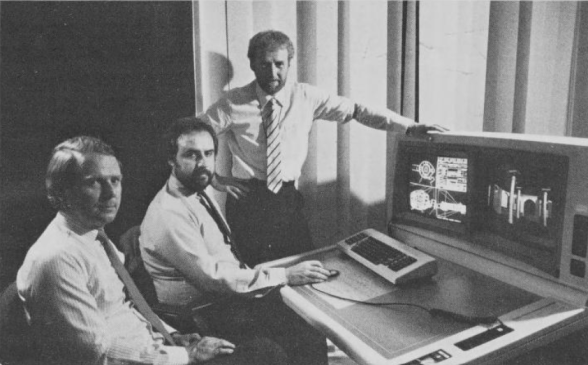

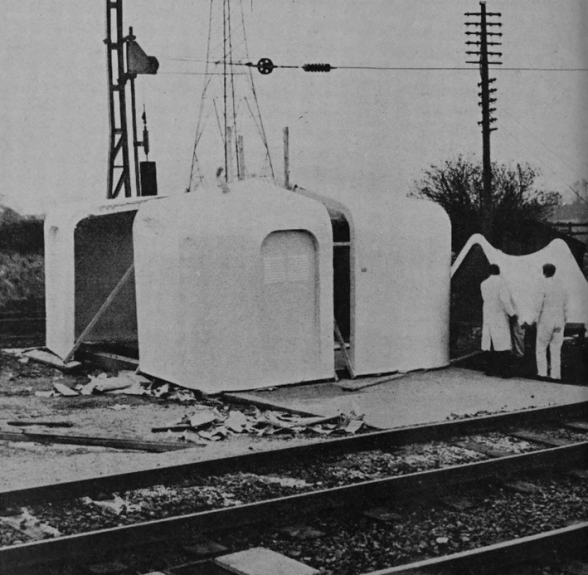

Image credit: Bob Hobbs, Anglia Television

Quarmby’s career had an interesting trajectory. He studied at the Leeds School of Architecture in the 1950s, joining the research and development team at British Rail, after failing to secure a job in the London County Council Architect’s Department. At British Rail, he experimented with the architectural potential of moulded plastic, designing transparent dividers for station booking offices and a modular system used to construct water-tight enclosures for new electronic signalling equipment. This modular system was celebrated by Archigram and adapted to create laboratories for the British Antarctic Survey and a series of telephone exchanges.

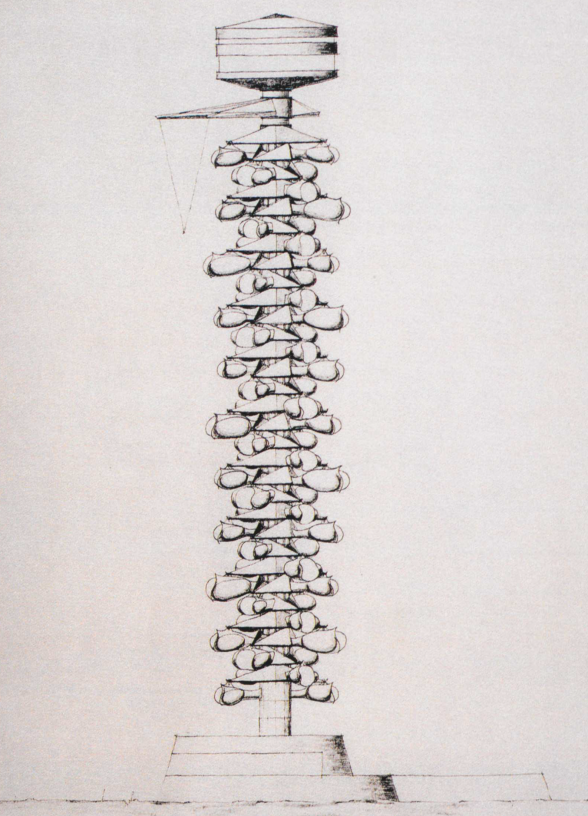

Image credit: Arthur Quarmby

By January 1960, Quarmby had moved into private practice, taking over and renaming the Huddersfield-based practice of the late Geoffrey Haigh. Quarmby continued to work on plastics after leaving British Rail, designing the largest self-support plastic dome in the world for the set of the 1968 film The Touchables, and writing a book on architectural plastics, titled The Plastics Architect (published 1974). He was also a prolific product designer, putting forward proposals for – among other things – an inflatable plunge pool for British Petroleum and designing a new form of odour-free urinal.

Image credit: Arthur Quarmby

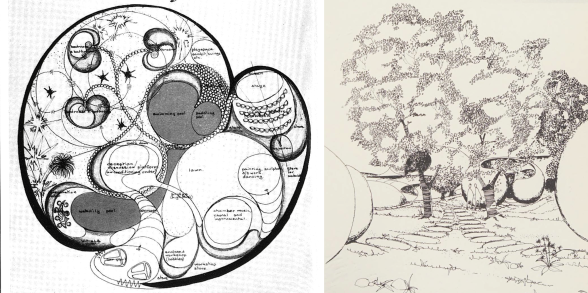

Quarmby drew up unrealised proposals for a series of flexible, high-density housing types in the early 1960s, believing that plastic modules would allow for greater flexibility in living arrangements and rapid assembly. In 1964, he devised House and Garden, a re-interpretation, which sought to dissolve the distinction between outside and inside. He envisaged a series of freestanding modules containing individual rooms, arranged around lawns, trees, a lily pond, and a swimming pool. A transparent plastic dome would enclose all of the modules and landscaping, creating a stable internal climate where inhabitants could live in harmony with nature.

Image credit: Architectural Review, Arthur Quarmby

The ideas developed in House and Garden, a re-interpretation went on to inform Quarmby’s designs for his own house, Underhill, which he began to draw up in 1969. Completed in 1975, Underhill was cut into the hillside and covered with earth. It was, as Quarmby put it, a form of ‘anti-architecture’, blending into the landscape, whilst the thermal mass of the earth meant that temperature and humidity levels in the house were kept consistent and comfortable.

Speaking to Building Design about Mole Manor just as construction began in 1985, Quarmby observed that, ‘part of the idea of earth-sheltered housing involves partly using what is excavated’ resulting in a house ‘unique to it situation and sympathetic.’ Some of the 2500 tons of Cotswold stone excavated from the hillside during construction were used to face the walls of the completed house, but Mole Manor was primarily built using concrete, with the floor and ceiling slabs poured in situ and blockwork used to construct the walls. A series of L-shaped concrete panels were installed parallel to the blockwork in order to hold back the soil.

Image credit: Architects Journal

Like Underhill, Mole Manor was a work of ‘anti-architecture’, being largely hidden beneath the earth. Where the building emerges from the hillside, the elevations are finished in rugged stonework. In the centre of the west elevation, a large circular opening contains the front door. Evidence of the Bilbo [sic] Effect in action, Quarmby had also used this formula at Underhill, with the influence of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings on Quarmby attested to by Underhill’s name.

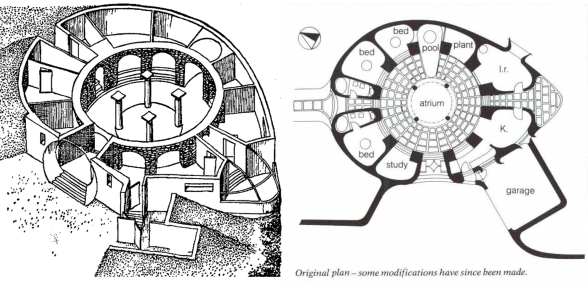

Mole Manor has an egg-shaped plan, tapering to the south. Quarmby originally built an observatory at this end, which had a plastic quarter dome sitting on a low rubblestone wall. Sadly, this whimsical structure was replaced in the early 1990s with a more conventional conservatory. Most of the natural light is drawn into the building through the domed plastic roof lights that protrude above the turfed roof, with a series of slender, deeply recessed windows allowing views out into the landscape. The subterranean nature of the building meant it was highly energy efficient, with a study by Bath University showing Mole Manor used 75% less energy than a conventionally built house.

Image credit: The Observer and Concrete Quarterly

The large, circular space at the centre of the plan was likened to a Roman atrium, with four pre-cast Tuscan columns set up on a dais supporting a 12-foot-wide plastic dome which floods the space with light. A 5000-gallon pool extended into the atrium from a recessed alcove, although this was later removed due to issues with mould.

Marriage and a new child meant Bexon needed to move out of his admittedly impractical bachelor pad. Bexon remained committed to the idea of earth-sheltered housing, devising a system for building underground called ‘The Molecule’ and worked with the engineer Tony Hunt to propose the first underground council house in the late nineties. Since Mole Manor was completed, the house has been sensitively extended to the north and north-west and the garage has been converted.

Image credit: George Perkin, Concrete Quarterly

Mole Manor is a rare and significant work of late twentieth-century architecture, resulting from the desire to create a building that would be both energy-efficient and comfortably integrated into the landscape. When it was completed in 1987, Mole Manor was one of only three modern earth-sheltered houses in the country, with Keith Horn’s Round House in Milton Keynes being the only one of the trio to not be designed by Quarmby. Despite its novelty, the house is clearly popular with its inhabitants. As one former owner said to The Independent, ‘[my husband] was working when we first moved in, but once he retired, he really didn’t want to leave Mole Manor at all, not even for holidays.’

Tom Goodwin is a PhD student at the University of Warwick studying British architecture at the turn of the millennium and secretary to the Twentieth Century Society casework committee.

Building of the Month is edited by Joe Mathieson; an Architectural Adviser at the Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust, writer and C20 volunteer. For pitches, or to discuss ideas for entries, please contact: joe@c20society.org.uk

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.