This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

July 2014 - Sassoon House, London

by Elizabeth Darling

At first glimpse, St Mary’s Road, Peckham, in south London appears much like any other in this part of London. A residential street, it is lined by rows of early- to mid-nineteenth century houses. Should you continue further down the road, however, towards the junction with Dundas Road and Belfort Road, two less ordinary buildings come into view. The first is the Pioneer Health Centre, a squat, bow-fronted, concrete-framed building, set back at some distance from the pavement. The second, occupying the corner between the Centre and Belfort Rd, is a block of flats: R.E.Sassoon House. Five-storeys high, it stands end-on to the main road, its cantilevered ‘family’ balconies overlooking Belfort Road.

Of the two, Sassoon House is the lesser known. Historians have tended to focus on its neighbour both for its dramatic architecture (the work of Owen Williams) and the rather curious ‘Peckham Experiment’ that it housed. But the flats are worthy of attention because they formed part of the Experiment and were intended as an intrinsic part of its founders’ plans to transform the lives and environments of at least some of London’s urban poor.

The ultimate origins of the flats, however, lie in a steeplechasing accident. In January 1933, Reginald Sassoon, amateur jockey son of the philanthropist Mozelle Sassoon, was killed at Lingfield. In his memory, his mother decided to commission a block of workers’ flats, an idea which may have stemmed from a new acquaintance. This was Elizabeth Denby, who was just embarking on her career as one of the century’s most important housing reformers, and was keen to find a ‘live’ project through which she could realise her vision of well-planned, well-equipped housing, with extensive amenities, all expressed in a new architectural language. Already collaborating with Max Fry on design ideas, they took the project to the doctors (Innes Pearse and George Scott Williamson) behind the Peckham Experiment, who were then developing the site on St Mary’s Road as the purpose-built Pioneer Health Centre.

Denby and the doctors had much in common. They all believed that modern urban life had broken up traditional communities and environments, something that had grave implications for the nation’s physical and corporate health. Crucially, rather than seeing reformed suburbs or garden cities as the solution to urban devitalisation, as they called it, our Peckham reformers insisted on the transformation of the city itself. Through architectural interventions they sought to make ‘a full and energetic life possible in terms of urban existence.’ The Centre and the flats were component parts of just such an enabling environment, the basis for a ‘genuine urban life.’

The Centre was the focus around which individual families could gather and cohere into a community; it provided extensive leisure facilities as well as health care, amenities which enabled them, in the doctors’ parlance, to be ‘brought to health’ and become active citizens (as well as producing healthy babies; there was a strong element of positive eugenics about the Centre). Sassoon House offered a complementary ultra-modern domestic setting – better-equipped than anything suburbia could offer and at an affordable weekly rent.

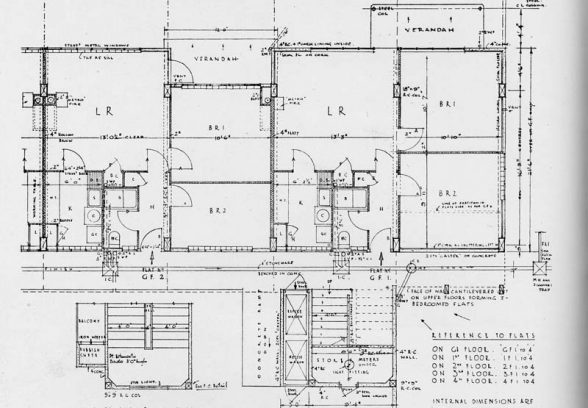

R.E.Sassoon House had twenty flats: three three-roomed (for 11s rent) and one four-roomed (at 9s 2d rent) per floor. Access was by galleries which were reached from the staircase tower. This was lit by a curtain wall of plate glass decorated with a vitrolite glass mural of a horse and rider by Hans Feibusch. Originally, a wall ran north between the tower and the perimeter wall to create a private yard for the tenants, which contained pram and bike sheds, a bench and drying rails. Exterior walls were painted cream, yellow, cinnamon and grey, colours which toned with the mural. The steel windows and balcony doors were painted bright blue, likewise the front doors.

If the exterior was striking, so was its interior. Here, for the first time in workers’ housing in Britain, Denby and Fry introduced the ‘existenz-minimum’ plan, a technique to use the minimum space for family life as efficiently as possible in order to keep building costs down, as well as provide a labour-saving working environment for the housewife (both Centre and flats were informed by a desire to re-establish gender roles in the family, something contemporary unreformed urban life was blamed for disrupting).

Each flat contained a large living room, a kitchen, bathroom and either two or three bedrooms. Although small, nearly 8 by 6 feet, the kitchen was planned to be an efficient and labour-saving work place. Along the wall adjacent to the bathroom, with which it was planned as a repeated unit, were lined a gas cooker, gas copper with draining board cover, a sink and further draining board. This arrangement allowed bathroom and kitchen to share plumbing and gas flues, thus minimising costs. The wall opposite held a larder and continuous work surface with shelves beneath. The whole room was lit by windows which looked onto the access balcony. The kitchen opened into the living room. It was equipped with a built-in cupboard and a brightly-enamelled slow-burning coke stove. The room was lit by large south facing windows and a glazed door which led onto the family balcony, which spanned the exterior of the living room and the rear bedroom. It contained a built-in flower box.

Fry, looking back at R.E.Sassoon House, spoke of ‘the cosiest flat’ and the block as ‘a perfect receptacle for close family life.’ While at its opening in November 1934, the Jewish Chronicle described it as ‘a veritable beacon in the housing history of our age.’

Today, neither building is what it once was. The Centre, which opened in 1935, was closed in 1951. Subsequently used for various purposes by the local authority, the site was sold and converted into ‘luxury’ flats in the late 1990s. Originally owned and managed by the Pioneer Housing Trust, Sassoon House is now part of the local borough’s housing stock; its interior planning completely changed during a modernisation programme in the 1980s.

Elizabeth Darling is an architectural historian, specialising in inter-war English modernism. Publications include Re-forming Britain (2007) and (forthcoming) the Introduction to a new edition of Elizabeth Denby’s Europe Rehoused.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.