This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

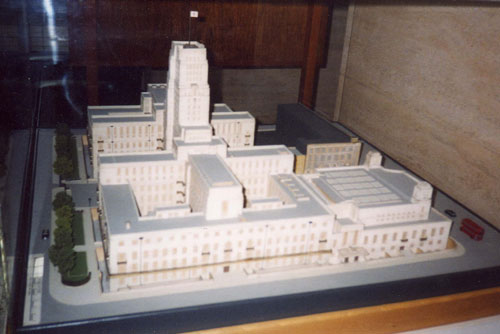

September 2003 - Senate House, Bloomsbury, WC1

The University of London’s imposing Senate House was constructed to last for hundreds of years, and it remains in near- original condition to this day, yet its style makes it one of Charles Holden’s less critically acclaimed buildings. The second tallest building in London when first built, it is best appreciated now from its immediate surroundings, or from the surrounding heights of North London.

In 1932 the University Court compiled a list of fourteen prominent architects to design its new headquarters building in Bloomsbury. The brief, as set by the University’s consultant, H.V. Lanchester, was for a style of architecture to ‘not suggest a passing fashion inappropriate to buildings which will house an institution of so permanent a character as a University’. Holden was selected, perhaps for his interpretation that this meant a building that needed to last for centuries. The popular fallacy he built it to last for 500 years, although commonly cited, is untrue.

He convinced his clients that conventional means of construction were preferable to a steel framed building, although the cost, together with the economic circumstances of the 1930s, meant that the overall scheme had to be dramatically scaled down. Only three of the four courts in the revised, or ‘balanced’ scheme, was completed. The construction was of brick faced with Portland Stone, vertically grooved, or ‘batted’, as a means of self-cleaning, with grey Cornish Granite below the first floor level. Travertine Marble was used throughout the public areas and staircases, and Holden designed many of the internal fittings, which still survive.

Ironically, his design for the London Passenger Transport Board’s headquarters at 55 Broadway, which had originally convinced University Court of his abilities and has many similarities, employed a steel frame. However the Senate House’s most significant difference was its lack of statues; Holden had long promoted controversial sculptors like Jacob Epstein, but he appears to have bowed to conservative opinions rather than risk difficulties elsewhere. The statues’ plinths still remain on either side of the tower, nevertheless.

The building’s style has long been the source of debate. Frank Pick, Holden’s mentor at London Transport, was distinctly critical. Some believe that it owes its lines to the American skyscraper, many others to European Modernism. While a modern feel is undoubtedly present in its massing, its stature, and its absence of detailing, there is undoubtedly also a Classicism in its rhythm, its fenestration and use of material. Holden considered that style should ‘grow naturally out of the adjustment of our ideas to changing conditions of life and changing methods of construction ~ only so shall we keep our architecture sane, and free from the element of ephemeral fashion’.

In May 1938, he told the RIBA that ‘the base of the tower is the best bomb-proof shelter in London’. As the wartime Ministry of Information, which inspired George Orwell’s 1984, it was hit by bombs several times, although only damaged slightly. It was rumoured that it survived because Hitler (no stranger to architecture built to withstand centuries) coveted it as the Nazi party headquarters had he successfully invaded Britain.

Nevertheless it has remained largely unscathed by bomb or administrator since: its sheer solidity makes any alteration an expensive option. Suggestions that the fourth unbuilt court be added has been deterred by the stipulations of English Heritage and the depressingly inadequate ideals of those who fund higher education today.

Charles Holden’s Senate House building, his last ever work actually constructed, has perhaps never been in vogue; nevertheless its distinctive character means that it cannot be ignored, nor overlooked for much longer.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.