This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

April 2023 - The ‘Solar Campus’, former St George’s School, Wallasey, Merseyside

Image: Elain Harwood

The ‘Solar Campus’, former St George’s School, Wallasey, Merseyside (1958-1961)

Emslie Alexander Morgan

Merseyside is not specially noted for its sunshine. True, Liverpool’s annual average of 1500 hours compares favourably with that for Manchester (1385) or Lake Windermere (1225). But that total palls against Yuma, Arizona (4015 hours), Perth, Australia (3200), Madrid (2900) or even Weymouth, the highest in mainland Britain with 1900 hours.

Yet it was Wallasey, on the Wirral, that saw the first school building in the world to be heated primarily by passive solar radiation. It was the work of Emslie Alexander Morgan (1903-65), principal assistant architect to the county borough, then an education authority. In 1955, the borough had opened St George’s School as a secondary modern for 300 girls, but three years later agreed to double it in size and admit boys. The original building was a typical 1950s school of brick, with timber panels and large single-glazed windows, typical of a decade when energy was relatively cheap and getting cheaper, and insulation not understood. The problem was that the additional building, which were to include woodworking and metalwork rooms, and a gymnasium as well as classrooms and laboratories, could not be built within the Ministry of Education’s stringent cost controls without the plan being deeper than usual and therefore harder to light naturally.

Image: Elain Harwood

This was Morgan’s chance. Born and educated in Aberdeen, he had completed his final qualifications only after war service and worked there for his younger architect brother, Frederick, until moving south around 1955. But, according to the deputy architect Charles Caven, he had had the idea of using the sun to heat a building for many years, and now he saw the opportunity to introduce a completely glazed south-facing wall to light and heat the new annexe. He produced plans, calculations, a model and finally a master plan, which was accepted in 1958 when work began.

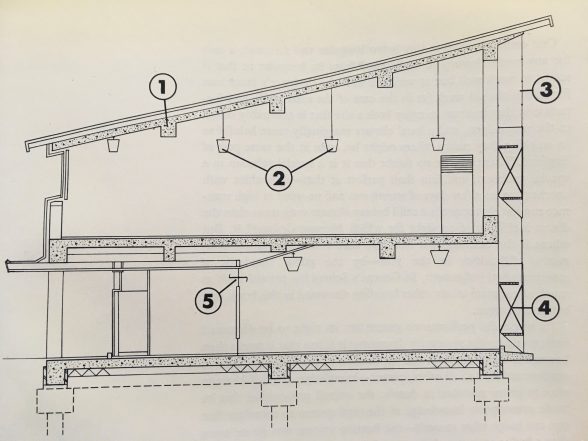

The building was erected in two phases, completed in 1961. The main range has a high south-facing façade overlooking playing fields and a slightly later wing facing south-east containing the gym, woodwork and metalwork rooms that could be kept at a cooler temperature. The south and south-east facing are complete curtain walls each with two layers of glass, two feet apart. One is clear, the other is made largely of translucent glass intended to defuse light through the building. The pivot-opening windows incorporated a grille so they could be safely left open for night-time cooling. The accent is on diffused light rather than views, though in places the inner skin was clear, in others it is a brick wall. At these points there are shutters – one side shiny white and the other painted black – that could be moved to reflect or absorb heat as required; a complete and motorised system was never installed, however, and the limited system was only reversed in spring and autumn. There were additional aluminium panels, one side shiny and one side black, behind the inner layer of glazing but these too were seldom adjusted. There are maintenance walkways between the two skins.

Image: Elain Harwood

The other outside walls and the monopitch roof are of thick concrete. These were insulated externally with five inches (12.7cm) of polystyrene, the best material then available, and protected from moisture by a bitumen vapour barrier on both sides. The north wall is lower and is almost blind save for ventilators that naturally draw air through the building. Any building with so much well-insulated thermal mass will have tremendous ability to even out changes in external temperatures, but here cross-ventilation and night cooling prevented excessive solar gain.

Wallasey CB insisted on an auxiliary boiler as a back-up, but when by 1966 it had never been used, it was cannibalised by other schools for spare parts. Its legacy is the building’s distinctive chimney. Meanwhile, it was the annexe’s good fortune to be completed ahead of the exceptionally cold winter of 1962-3. The Liverpool Echo reported that ‘In the coldest January for nearly a century, the temperature did not fall below 60 degrees Fahrenheit, and yet in a brief heatwave in June it was cooler than in another part of the building erected five years ago’. It also claimed that teachers flocked to work at the school, so pleasant was the environment.

Image: Elain Harwood

Morgan tried to interest the National Research and Development Corporation and Ministry of Science and Technology, but without success. He applied to register a patent, but died in February 1965 before it was approved, leaving a young wife and infant child but no record of his calculations. ‘Morgie was a genius’, admitted his boss deputy architect Charles Caven, ‘and we miss him. Sometimes we cursed him and his involved ideas, but he infected us all with his enthusiasm.’

There was interest in his ideas from Coventry City Council, but little support from the government. The Ministry of Public Buildings and Works funded a study that confirmed the building worked in both summer and winter. Morgan recognised that heat from the tungsten lighting and the students themselves would play an important role in heating the building. Investigating the patent, Liverpool University’s Building Climatology Research Unit agreed this would probably be the case, and Coventry did not pursue its interest. The truth of these findings became evident when the lighting system was changed, and still more when student numbers plummeted, but Morgan’s principles remained sound. ‘I’ve never felt chilly’, reported the headmaster, Leslie Bradshaw, in the late 1960s; ‘it seems strange that none of the higher ups took up the idea’. The council claimed to save some £600 on fuel bills, a huge sum for the time. The school would have remained almost unknown, had it not formed the climax of Reyner Banham’s The Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment in 1969. But for all the book’s significance, how many of us have actually read it all the way through?

Image: Elain Harwood

The solar annexe was Grade II listed in 1996 following the school’s closure due to falling rolls. For many years it housed the borough’s youth and community services, before re-opening as a pupil referral unit for students with problems, the Emslie Morgan Academy. It closed in July 2019 and Lynsey Hanley, writing in Tribune, reported on the lack of investment and inadequate facilities. Now it lies derelict. The rest of the campus is divided between the local probationary service and Tranmere Rovers Football Club, who use the former sports field as its training ground. The trainers keep a friendly eye on the building and know its worth, but can a new use be found for a building of such international importance?

Elain Harwood is an architectural historian with Historic England, expert in post-war architecture and author of numerous C20 titles (@Elain 540).

The Building of the Month feature is edited by Andrew Murray (@aaamurray).

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.