This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

December 2013 - Three Lane Ends Infants’ School, Castleford, Yorkshire

by Jessica Holland

Oliver Hill is recognised for his versatility as an architect, able to design in a range of styles, from Classical to Modern. Amongst his best-known Modern works are Joldwynds (1930–32) and the Midland Hotel (1932–33) in Morecambe, which characterise his early interest in glamorous new materials. Yet Hill’s engagement with modernism was not limited to stylistic concerns.

Hill’s work for the West Riding of Yorkshire Education Committee perhaps best illustrates his understanding and belief in the social agenda of modernism. Hill’s modernist viewpoint was built on his experience of Northern European centres of the Modern Movement: Stockholm, Vienna, Frankfurt and Stuttgart. His participation in a 1931 Architectural Association excursion to ‘Red Vienna’ was particularly influential and visits to kindergarten employing Maria Montessori’s education principles made an immediate impact on Hill’s architecture.

In 1937, Hill began work on two schools for the West Riding’s progressive education committee, which looked to undertake improvements advised by the Board of Education’s Hadow reports (1923–33). Chaired by Walter Hyman, the committee put in place a programme of school building to raise the school leaving age and provide modern facilities to improve the lives of its often underprivileged pupils. Hill’s appointment followed a series of commissions for the London County Council, designed in conjunction with the high-minded aims of Frank Pick’s Council for Art and Industry. Although unrealised, Hill’s L.C.C. schools demonstrated his progressive approach and made him an obvious choice for the West Riding committee.

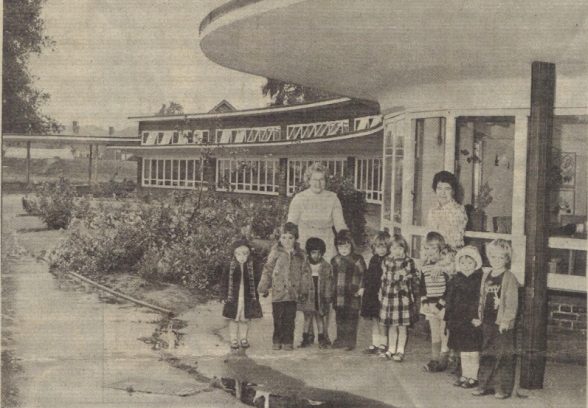

Hill designed Three Lane Ends Infants’ School at Whitwood Mere, on the outskirts of Castleford (1937–40) and its counterpart, Methley Senior School at Rothwell (1937–39), though the senior school remained unbuilt due to the outbreak of war. Hill’s modern schemes were a reaction to what he described as the ‘pernicious’, industrialized landscape. Both schools use forms inspired by transportation to spirit pupils away from the ‘grimy factories’ and ‘untidy sheds’ to an environment of ‘cleanliness and cheerfulness’.

Three Lane Ends School forms a gentle arc towards the sun, with an assembly hall placed at right-angles to the building on the north side. The curved form is replicated throughout the school; porthole windows, rounded corners and a sweeping canopy with bands of windows, all evoke the upper decks of an ocean liner. Methley School, meanwhile, is a more literal take on the transport metaphor intended to look like a recently landed aircraft, showing Hill’s characteristic wit. The aeroplane plan – a machine age interpretation of the Arts and Crafts butterfly plan – provides an efficient layout, with the fuselage housing a gym and assembly hall, and wings of south-facing classrooms to each side.

Hill’s choice of materials at Three Lane Ends School responded to the ‘drab’ landscape, with colour and texture intended to give the building character lacked by its surroundings. A lightweight steel frame is infilled with heather-coloured Yorkshire bricks, set with wide joints and a thin skin of celadon green faience over areas of the north façade. Adjacent to the main entrance, the faience tile manufactured by Carter’s of Poole is incised with a very successful frieze of life-sized, leaping beasts by the artist John Skeaping. Inside, a sunny palette of primrose yellow, pale green and tan was accented with bright orange and jade green tiles. Dadoes of coloured linoleum provide a continuous, washable surface and space for children’s artwork.

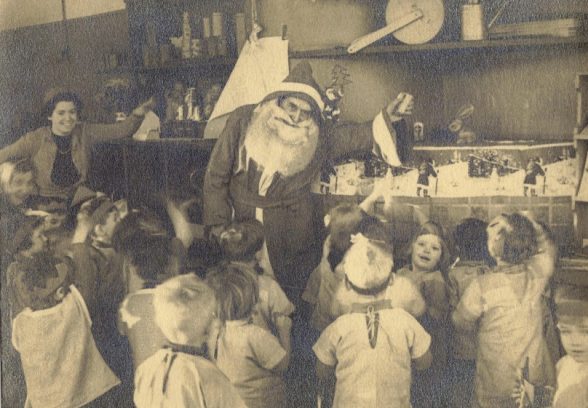

To the south, the glazed façade is split into eight bays, with five classrooms and a nursery room facing onto a shaded sun terrace. The windows could be folded away to allow open-air teaching in fine weather. The low-slung building is designed at the scale of the pupils, aged three to eight years old. Former pupils recall a ‘happy school’, which encouraged learning through play. Children’s welfare was monitored: infants were given cod liver oil and took an afternoon nap. Each pupil was provided with their own blanket identifiable by individual emblems, such as a green crab or blue bull, which also identified their coat peg. Hill also included facilities that would not necessarily be provided in the children’s homes, such as plenty of drying space for clothes. As the former Headmistress, Miss Brook, commented of Three Lane Ends School, ‘The whole place radiates an aura of controlled freedom’.

Many of these innovations came directly from Hill’s experience of European schools and nurseries, such as the Sandleiten Kindergarten (1924) in Vienna and Römerstadt School (1927–29) in Frankfurt by Martin Elsaesser. This precedent was complemented by input from his lifelong friend, the renowned child-psychologist, Margaret Lowenfeld. Three Lane Ends School was therefore a forerunner in infants’ education, combining progressive teaching methods, child welfare and modern architecture. High-profile visitors came to see this holistic approach, such as the Secretary of State for Education, R.A. Butler, who attended the school’s official opening.

Three Lane Ends School invites comparisons with the much better known Kensal House Nursery at Ladbroke Grove in London (1934–37) by Maxwell Fry and Elizabeth Denby, which also followed a progressive architectural and educational model. The only realised example of Hill’s educational building programme, Three Lane Ends School is the culmination of his ‘thirties modernist work and deserves to sit alongside Fry and Denby’s nursery as a pioneering example of interwar educational design.

Three Lane Ends Infants’ School was Grade II listed in 1980. Following its closure, in 1996 it re-opened as Three Lane Ends Business Centre.

Jessica Holland completed a PhD on the life and work of Oliver Hill in 2011. Following a two-year post as a Postdoctoral Research Associate at the University of Liverpool, she now works at the Chester office of Donald Insall Associates.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.