This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

January 2023 - Vice-Chancellor’s House, University of York,

The University of York’s Vice-Chancellor’s House, 1964

Robert Matthew Johnson-Marshall and Partners

Project architects: Alan Balfour and Colin Beck

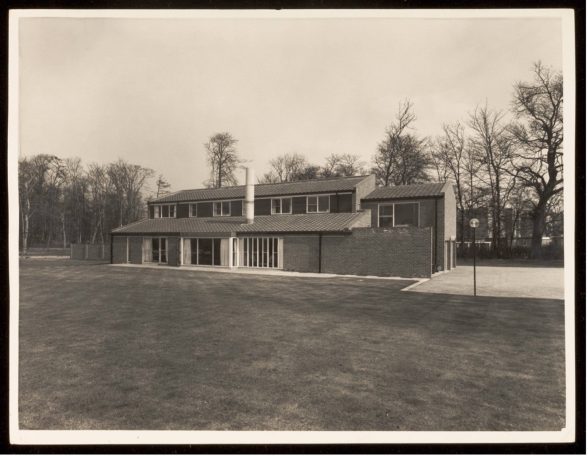

Within a burgeoning perimeter of deciduous and perennial trees, the Vice-Chancellor’s House of the University of York (founded in 1963), enjoys a large degree of privacy, albeit that it is located within the university’s lively campus. Its most distinguishing features include a central box-bay and a bi-folding window, the latter opening out onto a grassy lawn. Both are the height of the ground floor and are flanked by climbing jasmines and trellised roses. While familiar terracotta brick has been employed at the ground level, the first floor is clad in white weatherboarding and seems to almost protrude from a mono-pitched roof.

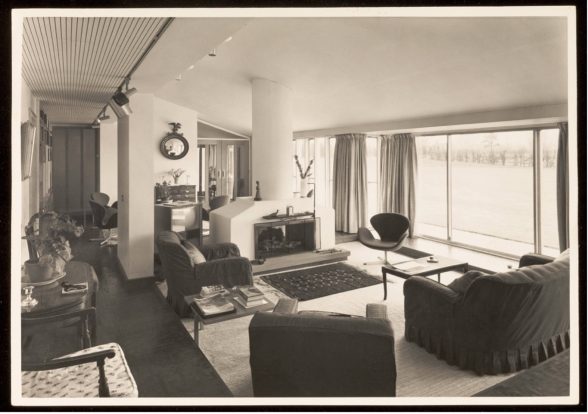

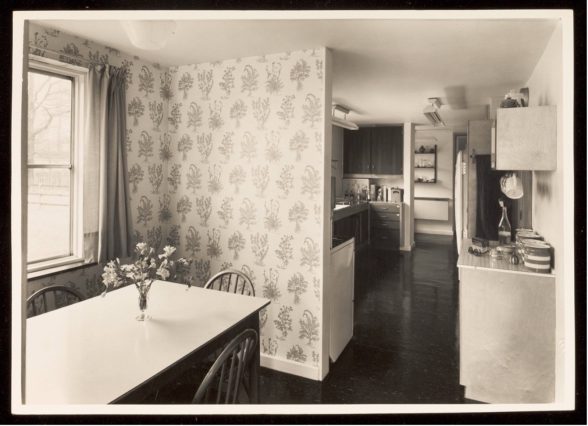

It was built for the University’s first Vice-Chancellor, Lord Eric James of Rusholme (1909-1992) and his wife, Lady Cordelia James, (née Wintour) (1912-2007). During the construction phase, architects Robert Matthew Johnson-Marshall and Partners (RMJM) invited Lady Cordelia to participate in conversations about the brief of the house. The interior, at least ostensibly, accorded with the building’s exterior and was predominantly contemporary in its style; functional pines, fabrics, coffee tables, abundant seating options and spot-light fixtures dominated. Perhaps less obvious though, is that these furnishings were a careful combination of modern and traditional tastes.

Credit: Borthwick Institute, University of York.

Credit: Borthwick Institute, University of York.

Homes and Gardens magazine (August 1965) afforded Lady Cordelia all the credit for this achievement. York’s new Vice-Chancellor’s House reflected, it said, ‘the tastes and hand of an imaginative and talented woman, who is both a devotee and patron of the best in modern art and design’. This praise was no doubt just and well-meaning, but there is a lot to be gained if we look beyond the anachronistic subtext. On this ‘talent’, there is, we might say, a famous design connection in this story – Lady Cordelia was the aunt of Dame Anna Wintour of Vogue, Condé Nast and her brother Jim Wintour. According to the latter, the couple were ‘committed to good value for money’ (Jim Wintour email to author July 2021). We might take from this that the interior design was not a reflection of any indulgence in contemporary style, but of a sensible and pragmatic approach based on careful and considered choices.

Jim Wintour also confirmed that their aunt served as a Justice of the Peace while at York, stating that she worked with the Magistrates Association to introduce suspended sentences. Alongside her views on contemporary design, a belief in modernity and modernisation as well as reform and opportunity underpinned Lady Cordelia’s principles.

York’s first Vice-Chancellor held similar convictions. Educated at Oxford, Lord James spent his early career in selective schools, arriving at York from Manchester Grammar School where he held the grand and imperious sounding position of High Master. Historian Dr Allen Warren, who got to know the Jameses at the beginning of his 40 years at York, felt that Lord James, had a paternalistic view of education and believed in the need to create a new ‘aristocracy of elites,’ (“A Poor Man’s Oxbridge?” in Utopian Universities: A Global History of the New Campuses of the 1960s, eds. Taylor and Pellew, 2020). His ambition was to replace the stuffy outdated aristocratic and Christian dominance with a new generation who would succeed on merit rather than social standing. According to all accounts, York’s first Vice-Chancellor was present on campus, approachable and always made time for anyone who wanted it. That Lord James was known affectionally as ‘Lord Jim’ at York is an indication of his character and of the warmth that was felt towards him.

A belief in opportunity and meritocracy was clearly shared between the Jameses, and their home had its role in advancing these ideals. The building was cleverly designed to function as a venue to host events. Jim Wintour believes that the house worked very well in this respect. He recalls feeling that the fireplace was a successful design solution, which divided the main space of the house. On one side was the living room, in which a homely and familial intimacy could be achieved. On the other, a space intended for entertainment which opened out to the gardens, encouraging guests to interact with the James and the university as though the two were as one.

At one event, Lady Cordelia’s nephew recalls that a group of overseas visitors were surprised to see that there were no servants, as he puts it, and that the Jameses were welcoming guests themselves. The suggestion being that they were humble and hospitable people – who sought to develop a democratic sense of community on campus, and who saw themselves as peers amongst their guests. While such stories are anecdotal, Anna Wintour, backs up her brother here, pointing out that Jim wasn’t attending these events simply as a family member, but as a student himself at the University. (Anna Wintour email to author, July 2021)

That this house was built on campus and in a conventional style was the gentlest of elbows to future Vice-Chancellors to follow Lord Jim’s example. The architects of the university, and Lord Jim, believed that the Vice-Chancellor’s role was to install themselves on campus as a true stakeholder in the university. There was certainly a belief that all Vice-Chancellors should be concerned, not only with the running of the university, but that they should be a visible presence, an example to its student body and intimately invested in its character, present and future. In 1966, Lord Jim stressed the importance of the unique collegiate university that was established at York. As James said in a lecture on “The Start of a New University” to the Manchester Statistical Society in February 1966: the university seeks to provide the ‘valuable intimacies and loyalties of the life of a smaller community […] it aims, moreover, at making closer relationships possible between teacher and taught’.

It is then regrettable to learn that this house has changed considerably since its early days. The fireplace and chimney have been stripped out and the furniture too has been removed. Worryingly, no record or inventory appears to have been made of either. In summer 2021, the Vice-Chancellor’s House lay unoccupied and had been employed as an overflow for kitchen provisions. More recently, the building has been used as student accommodation.

As the stewards of its first era, Lord Jim and Lady Cordelia established a set of traditions for future Vice-Chancellors: the pursuit of a meritocratic ideal and a close relationship between teacher and student. Whichever way you choose to measure it, Lord Jim’s efforts have been a resounding success. It is for York’s current Vice-Chancellor to decide whether this house should stand as it does today, as a sort of neglected monument to Lord Jim’s vision and principles – historical and somehow problematic, or whether this building is a living thing, – a trove of ideals and an epicentre of pedagogical opportunity. But a mausoleum to Lord Jim’s vision this building is not. Today, the University of York is much larger and arguably more disparate than the one the Jameses left in 1972. It is not only that the Vice-Chancellor’s House and the Jameses vision are important to the university today. Rather, there is a definite urgency for the continued existence of this building and a great necessity for the university that it welcomes its rightful occupant. There is also a hope on the part of some members of the University, to turn the house into a gallery to host the University’s rich art collection. Unlike the Grade II-listed Derwent College and Central Hall that neighbour it, the VC’s house is unlisted and extremely vulnerable.

Credit: Borthwick Institute, University of York.

This article is an abridged version of an original that forms part of York C20: an architectural gazetteer of twentieth century York. The Building of the Month is edited, for the last time, by Dr. Joshua Mardell.

Richard Burrows is a second year PhD student at the University of York in the Department of History of Art. He is researching the avant-garde in Russia, specifically the artist Kazimir Malevich and his ‘non-realisable’ architectural mission as it emerged within the movement of Suprematism.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.