This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

November 2023 - Woodhouse Medical Centre, Sheffield

Image: Google

Woodhouse Medical Centre, Sheffield (1987-1989)

Brenda and Robert Vale.

Brenda and Robert Vale studied architecture together at Cambridge before setting up their own practice. In 1972 they moved into the Horse and Gate, a former pub in Witcham, Cambridgeshire, where they were able to put into practice ideas they had been developing for low energy, self-sufficient, sustainable living. This included the installation of a wind turbine, superinsulation, solar cooker and solar hot water system, along with the provision of a smallholding for the production of food. As they described it, it was ‘a house in the country where they can experiment with alternative technology, keep a cow, chickens ducks, and bees, and grow their own fruit and vegetables.” This would provide the research and setting that would underpin their seminal text, The Autonomous House, written while living in the Horse and Gate and published in 1975. Intended as usable guide, the handbook offered ‘practical solutions to the building of a house that operates independently within its immediate environment…living in a way that does no despoil the earth – spending income, not capital.” From these relatively low tech, DIY ambitions, the Vale’s moved to Sheffield where they built up an architectural practice that provided them a platform to develop their ideas from the radical fringes of self-build, autonomous housing, to major projects for the public institutions. Perhaps the most high profile of their work from their time in Sheffield was a series of three medical centres for the Sheffield Department of Health: The Heeley Green Surgery (1985), The Woodhouse Medical Centre (1987-89) and the Birley Health Centre and Pharmacy (1992). All three explored the idea of superinsulation, which would become a central pillar of the Vale’s ongoing sustainability directives.

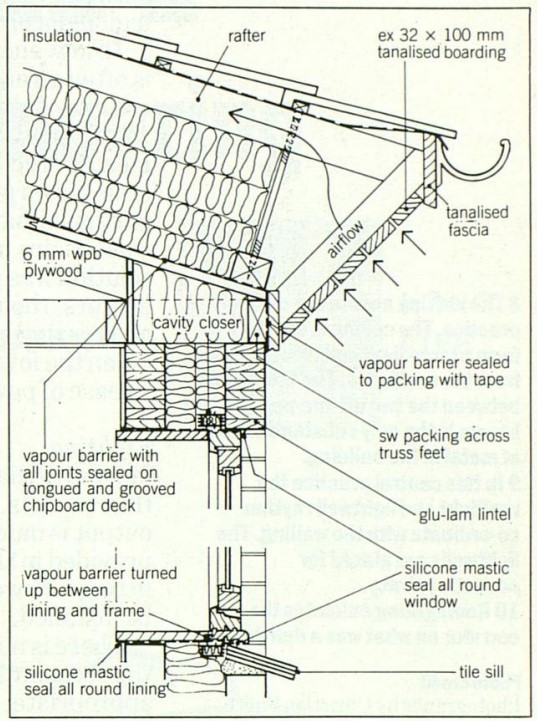

Image: Architects Journal

Superinsulation is a concept whereby a building is designed with much higher insulation and airtight standards than typical specifications. This provides an internal environment that is dry, comfortable, and retains heat at a rate far higher than standard specification, and thus requires less energy to heat it. The idea of superinsulation was developed initially in the late 1970s across North America and Denmark as a response to the oil crisis, and developed further in the UK by the Vales. The idea is seen as a precursor to the Passivhaus movement and the quest for ultra-low energy usage. Of their Heeley Green surgery, the first experiment in superinsulation the Vales wrote, ‘To heat the largest room in the building when it is freezing outside needs only the heat output of a doctor, a patient and a 100 W light bulb.’ In each of the three centres the level of insulation was increased, and the detailing of the various vapour barriers, air pockets and key junctions were refined in an effort to eliminate cold bridging and thermal bleed as much as possible.

Image: Architects Journal

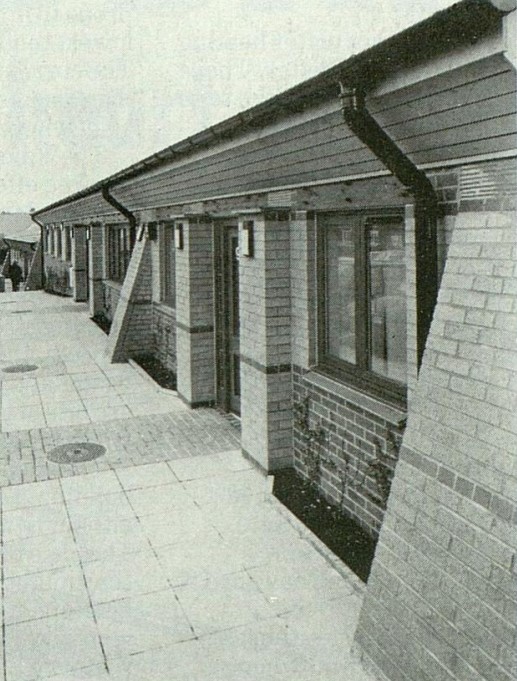

The Woodhouse Medical Centre is a long, squat rectangular building, with a slight crank in the centre of the plan. It was designed for three separate practices, a dentist and two general practitioners, all operating under the one roof, within the Sheffield Health Commission. It was designed to the strict briefing requirements and budget of the department, and in the end came in on time and completed under budget, quite a feat for a building with such strong sustainability ambitions. This was done through the canny design logic of the Vale’s. They paired the use of superinsulation with traditional construction techniques and locally sourced materials familiar to the local building trade. This allowed for competitive tenders and the use of established, long running building firms from the area, and resulted in a straight forward, uncomplicated build. Indeed, the architects describe the centre as a ‘thick building’ not a ‘smart building’ alluding to the deliberately low tech approach to sustainability.

Image: Architects Journal

Following this logic, the building is deliberately non radical in appearance despite its sustainability credentials. Formally, it draws heavily on the arts and crafts tradition with its low lying, solid mass, spreading gabled roofs and oversized timber detailing. It shows the Vale’s interest in straight-forward, low tech, and approachable construction logic, which was further developed by their interest in Christopher Alexander’s A Pattern Language that had just come out. It consists of banded face brick walls with creasing tiled details along the eaves, heavy, oversized timber lintels with exaggerated pegged construction details, and decorative barge boards and chunky oversized wooden eaves painted an earthy green which reveal the thickness of the roof. Each corner of the main building has exaggerated buttressed piers adding to the fortified nature of the building. The buttresses act as a device which enhances the illusion that this is a ‘thick’ building and gives a sly indication that there is more to this building than first appearances. The building uses timber roof trusses, glulam timber beams, bricks and concrete blocks and timber joinery throughout. The use of steel and metal are avoided where possible due to the high carbon cost of its production. The windows are low emissivity coated double glazed units with a 12mm argon cavity. These units were manufactured locally, but in subsequent projects the Vale’s would use high spec Scandinavian made windows which would prove more robust and long lasting. The use of a heat recovery system was introduced to further reduce heat loss through ventilation.

Image: Brenda and Robert Vale

In plan, the building is centred on a double loaded corridor that runs along the length of the building, lined with roof lights that flood the corridor with natural light. Utilising passive solar principles, these drastically reduce the need for artificial lighting. Light is filtered from the corridor into the consultation rooms via large, angled glazed panels which extend up to the ceiling. This allowed a building which required strict acoustic and visual privacy for the confidentiality of the patients to optimise its use of daylight. Each door to the consultation rooms is on a 45 degree chamfer, adding visual interest to the composition and breaking up the monotony of an otherwise very long corridor.

The superinsulation approach provides a thermal barrier and mass that is long lasting and a deliberately low tech. It is a low cost approach which significantly lowering the amount of energy consumed within the building. The roof has 350mm of thick insulation, and the walls have 150mm of insulation, the maximum allowable at that time and providing an insulation value 5 times required by current building regulations. This means that even in cold Sheffield, the use of artificial heating is minimal given the high performance of the insulated shell and its ability to retain heat. The building was awarded the inaugural Green Building of the Year award by the Independent on Sunday in 1992 and has a carbon dioxide emission lower than the lowest category listed in the BREEAM assessment method.

Image: Brenda and Robert Vale

Although the building has struggled over the years to perform as intended due to a number of factors it still requires very little heating and its energy use remains minimal. A post occupancy evaluation carried out by the Building Services Journal in 1996 rated the comfort level of the building as they best recorded by the Building Use Studies (BUS) Benchmarks and within the top 10% of surveyed buildings for perceived staff productivity gains. Following an award winning extension to the building in 2018 by Ikonografik Design, the building remains well used and stands as a compelling example of how sustainable principles can be built into a project at a fundamental level.

This entry was written by Andrew Murray, who edits the Building of the Month feature (@aaamurray)

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.