This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

The churches of the twentieth century are more varied architecturally than those from any other period in this country’s history. Whether their architecture draws on the language of the past or embraces new technology and symbolic shapes that herald the future, they reflect the personal expressions of faith of the architects and patrons that commissioned them, and touch on the changing social and cultural factors that have challenged and shaped faith. The Twentieth Century Society has worked with a rich and varied series of churches of late. Some are struggling to update facilities for changing times and deal with decreasing congregations. Others remain strong in numbers, but have design problems prompting their members to favour demolition and re-building rather than repair.

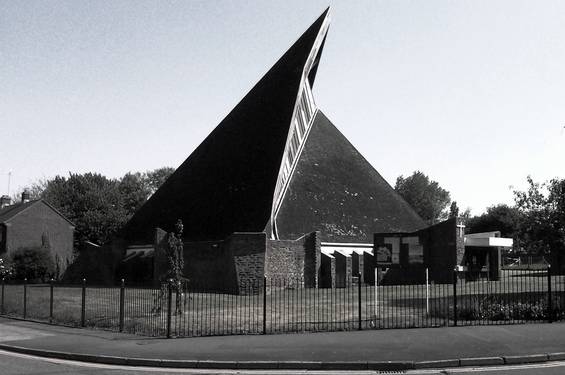

Tucked away in the suburbs of Gillingham, Kent, Holy Trinity is a landmark church that is threatened with demolition and re-building funded by adjacent development. The church is in need of repair, but the Society feels that its material problems are no more than are to be expected of any building of its age and can accommodate sensitive updating; the expressive architecture is strong enough to hold its own with any new build development. Happily it has recently been awarded Grade II status, less than two months after C20 recommended its urgent spot-listing, with support from local residents. We now hope that it will be eligible for grants towards repair and insulation of the roof to help it ensure its future at the heart of the community. Built in 1963, the striking cedar-clad pointed roof with a window split through is undeniably inspired by Scandinavian post-war churches, notably the Hyvinkaan Kirko by Aarno Rusuvuori in Finland (1961). The roof is grounded by thick brick walls that protrude and retract around deep-set windows, bringing to mind Le Corbusier’s Ronchamp de Notre Dame. Their sloping coarse brick surfaces (originally intended to be whitewashed) are designed to represent the ground from which they break. The building appears to erupt out of the ground, like a budding plant in spring. Inside the church, the square plan and diagonally-canted pews mark the adaptation to centrally orientated liturgical practice. The architect, Arthur Bailey, is better known for his austere Dutch Church in Austin Friars, London and restoration of blitzed churches, including Hawksmoor’s St George’s in the East. Quite what compelled such an otherwise conservative designer to embrace such a modern and sculptural form is a mystery, and we can only speculate that he was inspired by travels abroad or a fresh influence in the studio. Due to their modest character, nonconformist churches often struggle to inspire interest. But despite their lack of decoration, some recently threatened churches are a long way from the ‘preaching boxes’ of the previous century, and often show architects cleverly pushing economical materials to their limit.

Mitcham Methodist Church, in Merton, by Edward Mills, has a conventional rectangular plan made special by its folded slab roof (engineered by Ove Arup & Partners) which also creates a cloistered entry to the hall behind. The interior is defined by large windows to the top that draw the eye up, and a select choice of materials (hardwood floor and benches designed by the architect, the east wall clad in riven York stone). These, and the pulpit, lectern, altar handrail and simple chancel cross set a successful precedent for the interiors of Mill’s subsequent Methodist churches. At Norman Haines’s East Croydon Congregational Church the building takes an auditorium-shape plan. Both the interior and exterior side walls are expressed in rough granite stones set in panels; the west end is a generous curve of multi-coloured stained glass set between narrow concrete ribs: a colourful mixture of new and old glass taken from a nearby bombed church. Both buildings face re-building paid for by additional residential development. C20 has forwarded Mitcham Methodist Church, the best surviving work by the most successful non-conformist architect of the period, for listing at Grade II. Sadly listed churches are by no means guaranteed protection. Although their exemption from listed building consent procedures is allowed on the understanding that the alternative church procedures will be as rigorous as the secular system, in practice drastic alterations are often justified by changes in styles of worship and church use.

A recent cause for concern is the chapel of the Community of the Resurrection in Mirfield, West Yorkshire. The large Grade II listed chapel (1911-37) is the work of Sir Walter Tapper, one of the leading church architects of the early twentieth century, completed (after his death) by his son Michael. In addition to proposing a striking new monastery abutting the building, the community intends to remove much of the original furniture and fittings of the chapel including seats, screening, a hanging cross and large doors, and a set of stations of the Cross by Joseph Cribb, an assistant to Eric Gill. C20 is especially concerned about plans to level the altar steps and entire floor, replacing it with a tiled contemporary artwork. Although a formal planning application has yet to be submitted, C20 (with the Victorian Society) expressed strong objections to the extent of the proposals and hope they will be revised. We remain concerned that the community has yet to undertake a study of the significance of the building or a conservation statement which would guide them on a conservation-led approach.

St. Anselm’s in Kennington (1932-3 by Adshead & Ramsey), built to serve the surrounding neo-Georgian houses of the Duchy of Cornwall Estate, remains a popular church, but social depravation around its central London location has created a need for a community centre with a variety of facilities. Despite modifications since C20’s objections to a first round of pre-application proposals, the modest neo-Lombardic church would still be subdivided horizontally throughout, with toilets on the former altar site, and a new (and in C20’s view, inappropriate) double stair to the west entrance. The original decorative carved capitals would be visible only in a new café and bar space. The Society feels that the community is trying to squeeze too much out of a relatively modest building and small adjacent site and has again asked the church to re-think its ambitions.

Jo Moore

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.