This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

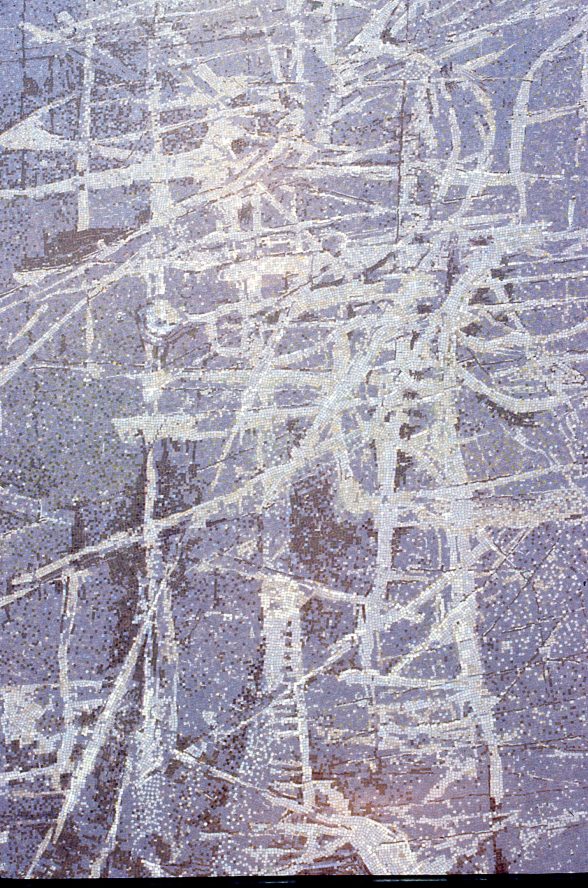

Photo courtesy Geoffrey Clarke

The Twentieth Century Society is disappointed by Historic England’s failure to recognise the importance of Geoffrey Clarke’s 1958 abstract mosaic in Basildon town centre and its decision to turn down our listing application.

The Society is requesting a review of this decision, claiming the reasons which have been put forward have been very poorly researched and argued.

The mosaic, which the Society considers to be of ‘outstanding national significance,’ has a prominent position on the second storey of a parade of shops, which are threatened with demolition.

The mosaic is of special interest as it shows Clarke, a leading sculptor, experimenting with a new medium in the late 1950s. It has been expertly composed and skilfully executed, and it survives in excellent condition.

Clarke was already working with Basil Spence (who was the consultant architect to Basildon Development Corporation) on the outstanding prestige project of the day, Coventry Cathedral, which is Grade I listed (where he produced the cross, crown of thorns and three stained glass windows between 1956 and 1962). He was subsequently commissioned by Spence (confirming the latter’s satisfaction with the creative relationship) for Spiral Nebula (1962), a sculpture outside the Herschel Building at the University of Newcastle which is Grade II listed.

The Society has consulted the art historian Dr Judith LeGrove who is the acknowledged world expert on Geoffrey Clarke’s work, having published “Geoffrey Clarke: A Sculptor’s Materials”, “Geoffrey Clarke Sculptor: Catalogue Raisonne”, “Geoffrey Clarke: A Sculptor’s Prints”, “Conjunction: Lynn Chadwick & Geoffrey Clarke”, and other writings. LeGrove has refuted HE’s reasons for refusal.

Fundamentally challenging Historic England’s point that this is ‘not one of his most important or successful works of art and has not been accorded a prominent place in his oeuvre’, LeGrove says: “Because of its scale and materiality this work occupies a unique position within Clarke’s oeuvre, according it greater significance than, for instance, some of his many commissioned works in aluminium.” She continues: “A huge percentage of this art, including Clarke’s, has already been lost through neglect or indifference: all the more reason to preserve this striking and singular example, which greatly enhances the context within which it is placed.”

In answer to Historic England’s argument that the mosaic is “only local in scale” and has no particular special interest beyond its role in the development of the town centre — a curious phrase lifted, uncritically, by Historic England from a letter written by the developer who opposes listing — she says: “Any commissioned art work is ‘local in scale’ in that it is produced for a specific location. The significance of this mosaic lies in its scale, the uniqueness of its design (it is not derivative, or like other work in the medium), and that it is a work by one of the most significant British artists of his generation working at the height of his powers.” In this sense, it is of national (and not just local) importance.

Again lifting a point made by the developer, Historic England have argued that the mosaic has an ‘awkward’ relationship with the building it is attached to and asserting that these elements were designed separately – an argument without documentary evidence and based purely on their “differing appearance” and alleged “lack of any physical and architectural relationship”. LeGrove points out that “Geoffrey Clarke never designed architectural works without consideration for their context: this was always his first consideration. Geoffrey’s father, John Moulding Clarke (1889–1961) was an architect and Geoffrey was brought up with an understanding, sympathy and fascination for the relationship between art and architecture.” The mosaic was clearly designed for this Basildon context.

Historic England also imply that the fact that the mosaic differs from the artist’s sketch serves to lessen its significance. LeGrove writes: “That the surviving artist’s sketch is markedly different from the mosaic-as-completed should in no way diminish appreciation of the finished work. Clarke often produced a range of alternatives as part of the design process, and it is likely that a sketch nearer to the final work was either lost or was given to an architect or commissioning body. The process of translating into mosaic by the artist’s wife [Ethelwynne Tyrer (known as Bill)] would have been done entirely under the artist’s supervision, and no alteration would have been made without his consent.” It is an original Clarke design which has been expertly executed.

Without listing the mural will lack protection if the proposed demolition of the building proceeds. Initially the plan was to relocate the mosaic within the entrance lobby of a new residential development, but different options have now been put forward which would see it continue to be on public view, which would be preferable, but it will be crucial to ensure that the demounting and re-erection of the mosaic is overseen by a specialist conservator, and that the new location is firmly secured and the process financed before demolition commences.

Nearly 500 one and two bedroom apartments are planned for the site, arranged in three blocks of up to 17 storeys. The application has been submitted by Orwell (Basildon) Ltd.

The buildings, Nos. 2-76, where the mosaic is currently located, were completed in 1958 and formed part of the town centre’s first shopping block. Constructed with a concrete frame and extensive glazing, it is believed it was designed by architect Lionel H. Frewster & Partners and the developer was Ravenseft Properties Ltd. While we appreciate that the building may not be listable, the Society and LeGrove nonetheless consider the mosaic to be of outstanding national interest. It is possible to list the mosaic separately, as outlined in Historic England’s Listing Guidance for Commemorative Sculptures, which notes that “For sculptures affixed to buildings, it is now possible to list only that part which has special interest. When the sculpture is of high quality, but the building isn’t, this selective approach can usefully be deployed.”

Back in 2016, Historic England’s exhibition “Out There Our Post-War Public Art” did a great job of increasing public awareness of the value of sculpture and mosaics, but as their linked publication “Public Art 1945-95. Introductions to Heritage Assets” states “the greatest threat to post-war public art installations is redevelopment.” Listing is by far the best way to counter this threat and ensure the survival of works which are widely cherished and enhance our streets.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.