This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

Image: Jonathan Taylor

A pioneering 1970s sports centre in Bradford has become just the third building of its type in the country to be awarded Grade II listed status, after an urgent appeal from C20 saved it from imminent demolition.

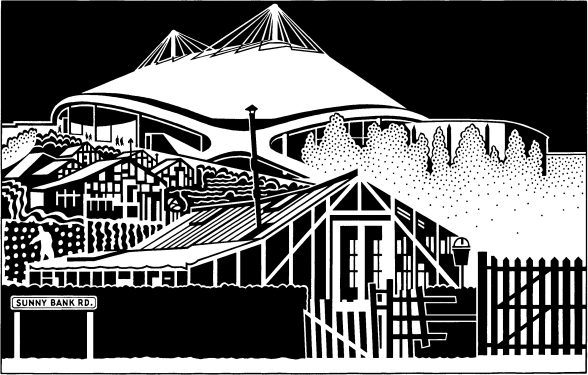

The Richard Dunn Sports Centre in Odsall, Bradford, was designed by local authority architect Trevor Skempton in 1974-76. Sitting in a prominent hilltop position to the south of the city centre, it was a conscious attempt to create a ‘permanent community landmark’, with its 40m-high cable-supported roof akin to a tented ‘big top’. Indeed, Skempton acknowledged the influence of Kenzo Tange’s Japanese national gymnasium in the elliptical concrete structure and Frei Otto’s tensile structures in the cable stay roof.

At a time when most offices didn’t have computers or even word processors, it was one of the first buildings in the UK to utilise computer aided design (in this case, the Genesys Frame Analysis 2 programme), which proved invaluable in calculations for the engineering of the cable stay roof.

Image: Jonathan Taylor

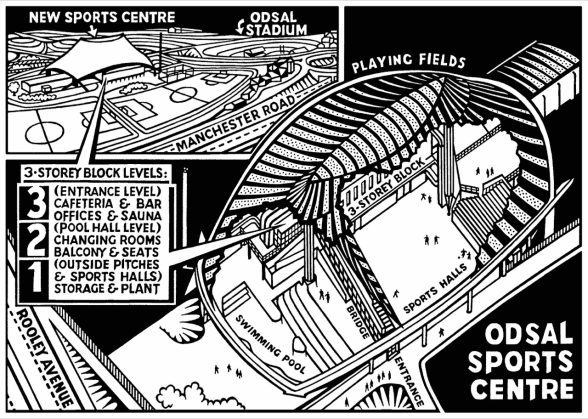

When it opened, the centre had a leisure pool, large multi-sports hall with terraced and expandable seating,

climbing wall, an upper hall, small sports hall, four squash courts and a shooting range, as well as a cafeteria and a bar/events room, offices and storage. Though the sporting provision remained relatively unaltered for 40 years, the interior space was designed to be flexible and with the expectation of change.

The council owned sports centre closed in November 2019, coinciding with the opening of the nearby £17.5m Sedbergh Leisure Centre complex. Permission for demolition was granted in February 2020 and delayed only by the Covid 19 pandemic, where the centre was pressed into service as a vaccination centre and standby morgue facility. Contracts with a demolition contractor were agreed in early 2022, prompting C20 Society to make a last ditch attempt to save the building via a listing application to Historic England. We were thrilled to learn this week that had been successful.

Image: Jonathan Taylor

In their report, Historic England credited the Centre for its ‘extraordinarily bold and ambitious design…a sophisticated and architecturally striking structure which provided a dramatic setting for the sports provision within’, adding ‘The greater ambition here reflected the council’s commitment to health and welfare, and social interest on the designer’s part in creating a theatrical experience to enhance the sporting one.’

With the listing designation focussing principally on the engineering virtuosity of the elliptical concrete edge beams and the roof structure, and not the rectilinear structures and facilities beneath it, there is a strong belief the centre could be adapted to suit a range of alternative uses.

After the listing decision was announced, local newspaper the Telegraph & Argus conducted a poll on whether the centre deserved to be protected. 55% per cent of the nearly 3,000 respondents agreeing with the designation and many enthusiastically offering suggestions for how the centre could be creatively repurposed. With Bradford one of the finalists for the UK City of Culture 2025, there’s a perfect opportunity to reimagine this city landmark as a centrepiece venue for a culturally and architecturally diverse city, looking optimistically to the future.

Image: Modern Mooch

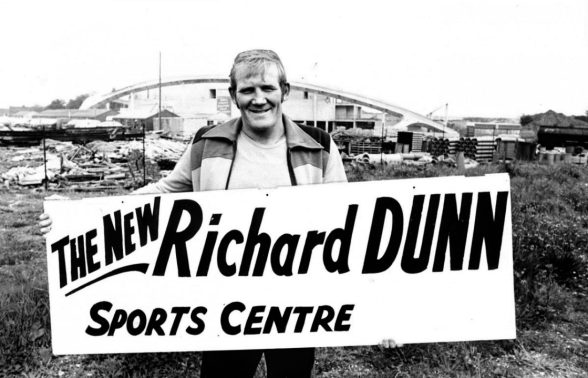

The story of how the centre came to be named, in honour of a local Yokshire sporting legend, is also the stuff of legend. Professional boxer Richard Dunn had won the British and Commonwealth heavyweight boxing titles in 1975 and the European title in 1976, earning him a showdown for the WBA and WBC world titles. Supplementing his boxing with stints as a paratrooper in the territorial army and work as a scaffolder, Dunn was actually working on the construction of Bradford’s new sports centre, when he downed tools to face Muhammad Ali in May 1976. Dunn ultimately lost the fight in five rounds – Ali’s last KO in the ring – but the newly completed Sports Centre was named after the hometown hero in 1978.

Credit: Building Design, September 8 1978

C20 Caseworker Coco Whittaker commented::

‘We are overjoyed that our listing application was successful and that this fantastic building will be saved from the bulldozers. The Richard Dunn Leisure Centre was built in the 1970s in the boom years of leisure centre provision in the UK and its unique tent-like roof is a superb example of the kind of bold and sculptural architectural structures produced to house these facilities in this period. We look forward to working closely with the local authority and Historic England to develop plans for the future use of the building’.

The Richard Dunn Sports Centre joins the The Dome Centre in Bury St Edmunds and the Swindon Oasis – also successfully campaigned for by C20 – as only the third listed local Leisure Centre in the country. Our Caseworkers are currently conducting a wider review of this often under-appreciated building type, with more details to be revealed in the next issue of our C20 Magazine.

Image: Modern Mooch

Credit: Building Design, September 8 1978

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.