This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

France: Douaumont Ossuaire

Architect: Léon Azéma, Max Edrei, Jacques Hardy

Location: Douaumont, France

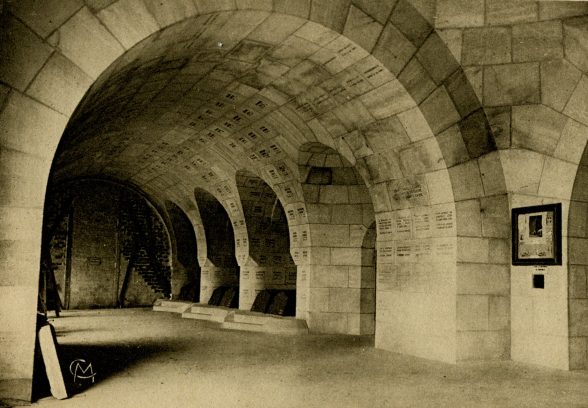

This unprecedented and disconcerting structure contains the bones of some 130,000 unidentified men – inevitably German as well as French – who died in the struggle for Verdun. The project was promoted by a committee convened by the Bishop of Verdun and was sponsored by non-governmental bodies and veterans’ associations. The foundation stone was laid by Pétain in 1920 but official approval of the design was not granted until 1924. The bones were transferred from a temporary ossuary in 1927 and the memorial building was inaugurated by President Lebrun in 1932. It consists of two long barrel-vaulted wings flanked by a series of alcoves containing sacophagi, expressed externally by gables, which contain the bones; the internal walls are lined with tablets bearing the names of those who disappeared. Projecting westwards from the centre is a chapel, with stained glass by Georges Desvallières and on an upper floor there is a museum. Above the central entrance rises a tall lantern tower. In this hangs a bell, the Bourdon de la Victoire, given by Mrs Anne Thorburn Van Buren in 1927. The lantern, which was designed to illuminate the surrounding battlefield at night, rises to 46 metres and the ossuary is 137 metres long. The architects were Léon Azéma, Max Edrei and Jacques Hardy. This partnership would win the competition of the Palais de Justice in Cairo in 1924 (along with Victor Erlanger) and Azéma was chosen in 1934 to be one of the architects of the Palais de Chaillot in Paris.

The architecture is certainly remarkable. With its curved roof and rounded ends, and the helmet-like top to the tower, the building has a military, fort- or gun-emplacement-like appearance. The style is hard to describe: a sort of stripped Classical-cum-Romanesque, with a Déco character as well as with hints of the sublimity of monuments of the Ancient World (typical of so much architecture of the 1920s), while the integration of the giant cross into the obelisk-tower has overtones of contemporary Expressionism. The ossuary has been largely ignored in the literature about C20 French architect and the design had and has its critics; J.-M. de Busscher has written of “Une architecture submersible don’t le phare-périscope, aux forme phallo-balistiques, veille les 130,000 corps immergés sous lui… Sous sa responsabilté: celle de l’obus qui le symbolise.” Roderick Gradidge wrote that “the vast vaulted interior” of the chapel, “lit by standard lights shining onto the ceiling, is extraordinary and quite successful and rather moving, reminding one if anything of Franco’s under-mountain memorial to the Spanish Civil War. There is nothing of Lutyens or the other British architects of the War Graves Commission, cool but none the less deeply felt emotion, to us perhaps this seems too extreme and too unreal.” While Jonathan Meades considers that “the vast ossuary at Douaumont is a matter for shame. It is shockingly inappropriate. Léon Azéma, Max Edrei and Jacques Hardy were not architects of the first rank. And they adopted an idiom peculiar to French and Belgian sacred architecture of the 1920s and 1930s. In the hands of Paul Tournon… or Jacques Barge, this wilfully exotic, vaguely oriental art deco is charming: if you like your churches to resemble cinemas, it is just the ticket. But even had Azéma and his collaborators been less ham-fisted, the very style, which might derive from an illustration by Willy Pogany, could only be counted a frivolous mistake – a mistake exacerbated by its proportions… The architecture of pleasure, monstrously distended, is inimical to meditative remembrance. The designers seem not to have had the nerve to address the awful purpose of their monument, and shamefully made light of it – they effected a betrayal of the dead.” [New Statesman 17th July 2006]

On the other hand, the designers were faced with an unprecedented brief and responded in a way that both looked to the past and acknowledged contemporary influences. It is surely more original and more distinctive than the memorial structures in other contemporary French cemeteries (such as Notre-Dame de Lorette near Arras), which tend to the conventional and ecclesiastical in character. It is certainly very different from Lutyens’s great memorial at Thiepval which was unveiled the same year (1932), and arguably rather less subtle and refined, but both, in their different ways, are highly original works of art which rise to the Sublime and express their terrible purpose without sentimentality. And if the Memorial to the Missing of the Somme is the greatest British monument to emerge from the war, so the Douamont Ossuary is the most important as well as the most haunting war memorial in France.

Gavin Stamp

Either enter the name of a place or memorial or choose from the drop down list. The list groups memorials in London and then by country

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.