This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

Image: FaulknerBrowns Architects

Riding the crest of a wave (machine) after the recent listing of Swindon’s Oasis Leisure Centre (Gillinson Barnett & Partners, 1976) and Bradford’s Richard Dunn Sport Centre (Trevor Skempton, 1976), the Twentieth Century Society is today launching a new nationwide campaign to celebrate the architecture of the leisure centre and to protect the most historic examples.

Leisure centres are places of community identity and an intensely evocative part of our shared social heritage: flumes, verrucas, palm trees, the smell of chlorine, the sound of laughter – this is the backdrop to childhood experiences and families at play. Yet they’re also some of the most architecturally innovative structures of the late twentieth century, combining environmentally controlled environments with soaring engineering and playful pop imagery. Is there any other building-type that’s as wildly varied and downright eccentric? Space-age geodesic domes, diamond glazed pyramids, castellated forts, brutalist elephants and Moorish postmodern palaces are just a few of the highlights of this idiosyncratic genre.

Some key examples remain from the 1970s boom in publically-funded municipal leisure centres, others are playful evolutions on the theme from more recent decades, while the exotic continental import of Center Parcs signalled a later shift to a packaged holiday experience. Most were designed around a free-form tropical pool, others focussed on hard courts and recreational sports. All are underappreciated and unexamined buildings in need of our support.

Image – Manor Photography

‘All pools at risk’.

The decimation of local authority budgets over the last decade has already forced many centres to close, with the challenges of the past couple of years only heightening the threat they now face. The Covid pandemic, global chlorine shortages and the soaring energy costs have meant that, in the words of Swim England’s chief executive, “Every pool is now at risk”. A report commissioned by the national governing body in September 2021 – prior to the current energy crisis – estimated that 40% of public pools in the country (1,800+ sites) could be forced to close by 2030. Even Swindon Oasis, added to the national list less than a year ago, has faced threats of a de-listing attempt by developers and the local Conservative administration, unwilling to invest in re-opening the centre.

Thirty years after the Societies ‘Farewell my Lido’ campaign started the movement to save our vanishing outdoor bathing heritage, we hope this sequel will stir the same appreciation for these subtropical places of pleasure and play. The time to act and preserve the most notable leisure centres is now.

Image – Jonathan Taylor

FaulknerBrowns Architects at the fore

From Cornwall to the Shetland Islands, we’ve scoured the length and breadth of the UK to identify the most outstanding examples of leisure centres, submitting ten to be considered for listing to Historic England, Historic Environment Scotland and Cadw (Wales).

Five of the ten cases put forward are by FaulknerBrowns Architects, the Newcastle-based practice who led the way in leisure centre development from the 60s to the 90s. While their ground-breaking Bletchley leisure centre – a huge diamond plastic and steel pyramid, similar to I.M.Pei’s celebrated addition at the Louvre – was sadly demolished in 2010, their surviving projects effectively plot the design evolution from community sports to Leisure Centres.

From the Walker Activity Dome (1965) near Newcastle, a facility geared toward the recreational sportsperson, with hard courts beneath a timber framed dome, to the Concordia Leisure Centre in Cramlington (1973); a plain, boxy brick, top-lit structure, with provision for both leisure and competitive swimming, with a sports hall that doubled up for social events and concerts. By the time of their later pool projects in Perth (1988) and Doncaster (1989), the emphasis was firmly on entertainment and eye-catching design, the latter featuring postmodern cupolas, pastel banded stonework, decorative steelwork with shades of the Alhambra and a glazed rotunda dubbed a ‘mock Pantheon dedicated to the gods of leisure’.

Image – Fraser Band

Bells Sports Centre, Perth – David Cockburn (1968)

When Bell’s Sports Centre opened in Perth, Scotland, in 1968, it was billed as the largest laminated timber dome in Britain, its span only being surpassed by London’s Millennium Dome in 1999. Despite comparable dome designs elsewhere – like Swindon’s Oasis and the Walker ‘Lightfoot’ Dome – Bell’s Sports Centre is unique in Scotland.

The centre was designed by Scottish architect David Cockburn, with a structure containing 36 arch ribs and supporting a 67-metre-long roof, 15 metres tall at its apex, culminating in a raised ventilation oculus. This provides more than 3,000m² of space for a running track and multi-use community sports, including tennis, badminton, basketball, gymnastics, indoor football and many more. During construction, parts of the city came to a standstill as the giant arches for the dome started to arrive by road, with streets closed and a police escort provided. The opening of the centre was delayed after a fire on 18 February 1968 badly damaged the structure, eventually opening in October of that year.

The centre is still in active use today, clocking up an estimated 12 million visitors since its opening 50 years ago. Over time the complex has expanded to include squash courts and a coaching hall, and the external cladding on the dome has been replaced a number of times, yet it remains the striking centrepiece and a feature worthy of recognition.

Image – Architectural Review

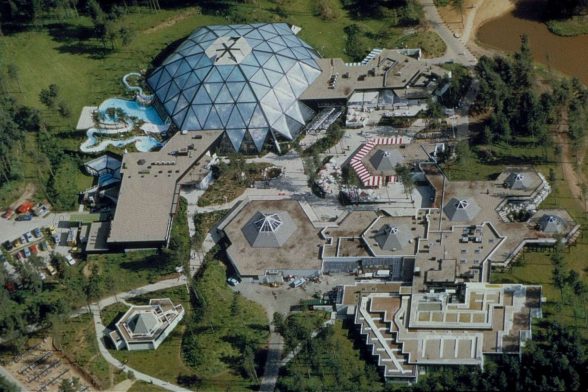

Center Parcs Dome, Sherwood – Center Parcs Architects (1987)

The Center Parcs model transformed European holiday culture. By the 1970’s holiday camps had fallen in popularity, overtaken by cheap package tours to the Mediterranean. By constructing communal holiday sites in accessible locations across Northern Europe, Center Parcs stemmed this tide. With significant private investment, Center Parcs also attracted recreational visitors away from municipal facilities.

Before establishing its foothold in England, Center Parcs had seven sites in the Netherlands, one in Belgium, and others under construction in France and Germany. Having identified the suitability of Sherwood Forest for their first UK project, Center Parcs rapidly progressed with a scheme totalling £31 million. The English Tourist Board contributed its largest grant to date – £1.5 million – towards the project

Built in 1986-87, the 70m diameter geodesic dome of the Subtropical Swimming Paradise provides the centrepiece of the holiday village. Glulam beams support a vast structure, clad with translucent ETFE panels, that covers a free-form pool with sub-tropical greenery and boulders imported from the Netherlands around the edges. It was designed by Center Parcs’ in-house architects in the Netherlands, originally led by renowned architect Jaap Bakema, a leading member of Team X, with Ove Arup & Partners acting as consulting engineers.

Minor alterations to the dome have been made since construction, with extensions in 2000, 2003 and 2016, but these works have so far avoided irreconcilable loss of the original fabric. The importance of the Sherwood dome is only increased by the extensive fire damage which resulted in significant restoration work at the second Center Parcs village at Elveden (1989).

Image – Shetland Recreational Trust

Clickimin Leisure Complex – FaulknerBrowns Architects (1985-2005)

Commissioned by the Shetland Recreational Trust using revenue from the offshore oil industry, Clickimin Leisure Centre in Lerwick was the first element in a masterplan to transform the leisure and sports facilities of the Shetlands. Constructed in three phases between 1985-2005 by Faulkner-Browns, it was to become the central star in a constellation of leisure centres across the Islands, the design being replicated in smaller forms in Unst, Yell, Whalsay, Scalloway, North Mainland, South Mainland and West Mainland. These all feature similar designs with low-pitched roofs, porthole motifs, timber fittings and internally exposed roof structures.

The building is partially sunk into the ground, nestling itself into the slope leading down to the Clickimin Loch – an approach mirroring that of the Shetlands’ traditional buildings, which hug the ground to withstand severe weather conditions. The sloping roof (the largest in the Islands) is exploited to provide additional headroom for the multi-purpose hall, while ancillary spaces enjoy a more intimate atmosphere. The materials were also selected with weather and local traditions in mind; the envelope is tightly enclosed by concrete blocks, portal frames on and an almost agricultural metal roof deck. The modest façade has been described as a ‘cottage style front’, finished with a harling of white quartz chippings, with the elevations broken up by appropriately nautical ‘porthole’ windows.

The centre cemented its place in local folkore by hosting The Smiths (in 1985) and Pulp (in 1996), bringing two of Britain’s most legendary bands the northernmost town in these isles at the height of their fame.

Image – Historic England

Coventry Sports Centre – Coventry City Architect’s department, 1973-76

The zinc-panelled Coventry Sports Centre (known affectionately as the Elephant) is one of the city’s most distinctive buildings. It is connected to Coventry Central Baths (opened 1966) by a walkway enclosed within its glazed ‘trunk’, leading to multipurpose spaces, including the main three-storey sports halls. The Elephant was constructed in 1977 after a small site to the east of Coventry Central Baths became available following the construction of the Coventry ring road in 1972. The building was designed by Terence Gregory and Harry Noble from the City Architects’ department, with suggestions its zoomorphic form was in homage to the same animal on the city’s crest. Its north elevation is particularly notable, with Cox Street running beneath its belly, and a series of triangular forms evoking an elephant’s head and ears.

The building was in use until February 2020 when it was closed by the City Council. Though Coventry Central Baths was Grade II listed in 1997, and the two buildings were intended to work as one, the Elephant building remains unlisted with its future uncertain. It represents an admirable rejection of the trend towards more restrained box-like forms, embracing and further developing the eclectic geometry of the pioneering leisure centres. There are increasingly few of the more playfully imaginative examples left, while much of Coventry’s post-war architectural legacy is also being erased.

As a footnote, Coventry’s period as City of Culture in 2021 renewed interest in the city’s post-war architecture, with the building featuring prominently in ‘The Bird and the Elephant’ – a film screened as part of the City of Culture celebrations – and appearing as a popular motif on merchandise and messaging.

Image: Cramlington Archive

Concordia Leisure Centre, Cramlington – Faulkner-Brown Hendy Watkinson and Stonor (1973-77)

Constructed at a cost of £2 million, Concordia was a significant addition to the developing new town of Cramlington – then less than a decade old at the time of its opening by the Queen in 1977, her Silver Jubilee year. An early Faulkner-Brown Hendy Watkinson and Stonor project, the Concordia contained a tropical leisure pool with palm trees and live planted landscaping, indoor football pitches, and other recreational sporting facilities. Just four months after opening, 50% of the local population of 22,000 had enrolled as members. Rooms could be booked for dancing or private dinners, while the pool could even be hired for special Caribbean evenings complete with barbecues and steel band.

Contrary to many contemporary leisure centre designs, the Concordia stands out for its compact volume and plan, with restrained brick elevations, punctuated by nautical porthole windows and relatively little glazing. Inside however, the steel spaceframe roof over the main pool fills the space with natural daylight, its series of glazed barrel vaults a prominent structural feature.

The Concordia underwent various refurbishment projects in the early 21st century and was most recently refurbished by the architects JDDK in 2016. It is still in use today with the freeform swimming pool as per the original design, sports hall, bowling alley, squash courts, climbing wall, and cafe.

Image – FaulknerBrowns Architects

The Dome, Doncaster – Faulkner-Brown Hendy Watkinson Stonor (1986-89)

Is this palace of pleasure Yorkshire’s postmodern Alhambra? Another Faulkner-Browns construction, the Doncaster Dome was considered to be the firm’s most ambitious building to date, combining and refining elements from previous projects. It was conceived as ‘a park for the twenty-first century’ and constructed on a discarded 320-acre former coal-field site on the eastern edge of the city. The building was opened in 1989 by Princess Diana and its success was such that it recorded a million visitors in 1990.

The irregular design features many Post-Modern motifs throughout; mock pilasters adorn the health suite like a Roman baths, with banded masonry creating a polychromatic effect, drawing allusions to classical buildings like Siena Cathedral. Elsewhere the 650 tonnes of structural steelwork, in tapered perforated I-section columns, meet the masonry columns in a satisfying junction of old and new technologies. Perhaps the most striking space is the atrium: a glazed rotunda, 30m in diameter and 19m high, with striped columns around the perimeter holding up the steel oculus, described as a ‘mock Pantheon dedicated to the gods of leisure’.

Among the attractions advertised were the largest flume ride in Britain – which meanders through the entrance mall and atrium and drops three and a half storeys over a 120m distance – plus the first experiment in a ‘leisure ice’ feature, applying the principles of a free-form pool to an ice skating rink. The centre’s four principal areas are all arranged around a circulation spine that encourages casual visitors to explore the building and provides window views of the various activities in progress. The complex was surrounded by manmade lakes and mounds to bring variety to its outdoor surroundings.

The Dome was envisioned as an extension of the city, not an entity that was separate from it, and is still in use today. Despite the vast scale of the design, the range of spaces have avoided the need for any alterations. Besides minor changes to some doors and fittings, the design remains in its original form, successfully serving its original purpose.

Image – FaulknerBrowns Architects

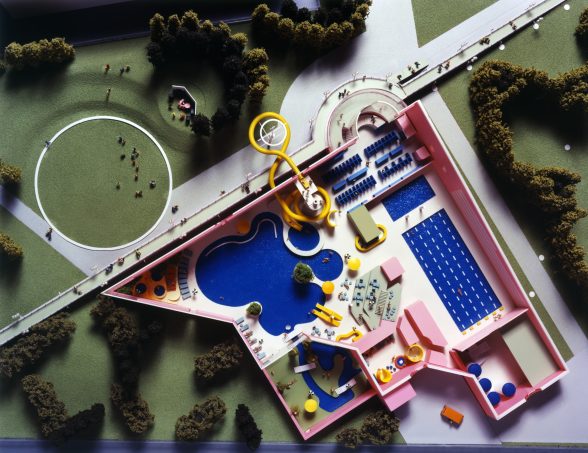

Perth Leisure Centre – FaulknerBrowns Architects (1984-88)

Built in 1984-88, Perth constituted a shift in the typology for architects Faulkner-Browns, with the intent to create a regional tourist landmark. The design represents the mature phase of post-war leisure centre construction, applying lessons learned from the previous two decades. This is reflected architecturally – particularly along the striking West façade – with an eclectic arrangement of features to attract attention. The design was widely praised for its futuristic design at the forefront of leisure centre developments.

Built on an equilateral triangular plan, the site is bisected by a raised pedestrian footbridge. The two flumes of the leisure pool dramatically pierce out from the western façade over the heads of those on the bridge. One flume circumvents a flagpole, which rises up to attract attention from a distance, while also structurally supporting the flume. A band of glazing runs across the top of this façade, topped with two barrel-vault glazed tubes which provide top lighting for the leisure pool. The building received an award from the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) in 1989, a Silver Award from the International Association for Sports and Leisure Facilities and commendations by the Perth Civic Trust and the Royal Fine Art Commission for Scotland.

Perth & Kinross councillors have approved a £90m budget for a new leisure centre to replace the existing pool, scheduled to open in 2027/28. While the budget has been approved, no planning proposals have yet been submitted and there are hopes the centre can still be saved. The venue continues to attract 400,000 annual visits and could be refurbished for a fraction of the proposed cost of a replacement, with ample room on the wider site for further expansion if necessary.

Image – Robertson Partnership

Ships and Castles Leisure Centre, Falmouth – Robertson Partnership (1992-93)

While most Leisure Centres can be found at the anonymous periphery of a town or city, Ships & Castles is dramatically sited above Falmouth harbour on the Pendennis headland – this unique setting informs its contrasting front and rear elevations, the resulting building defying stylistic classification.

On one side, a defensive entrance façade of castellated brickwork that faces and references Pendennis Castle – an artillery fort erected by Henry VIII in the 1530s, under the threat of French invasion. Six stout crenelated turrets are surpassed by a tall, pitched, slate-tiled roof, with four buttresses in brick and stone on each side. On the other side, a dramatic sloping ‘glazed sail’ provides panoramic views over Falmouth Harbour, shipyard and the National Maritime Museum Cornwall (2003). This fan glazing covers more than three-quarters of the building’s footprint, spanning across the whole pool. A nautical theme is apparent throughout the interior, with portholes and a large ship-like circulation structure attached onto the eastern wall, complete with funnels and an affixed lifeboat.

In 2015 the centre ran into financial difficulties, with a petition managing to stave off closure. In 2017, Cornwall Council handed the leisure centre over to Greenwich Leisure Limited (trading as Better) as part of a 25-year operating contract. Better recently announced that it could no longer afford to run the centre and it closed in March 2022. Cornwall Council’s Cabinet agreed in July 2022 to allow for 6 months of devolution discussions so that Falmouth Town Council and any other community organisations can draw up formal bids to take on the centre. While a local campaign to save the centre has received substantial support, if after this period no devolution agreement has been reached, Ships and Castles will almost certainly be demolished. A decision will be reached by 20 January 2023.

Image – FaulknerBrowns Architects

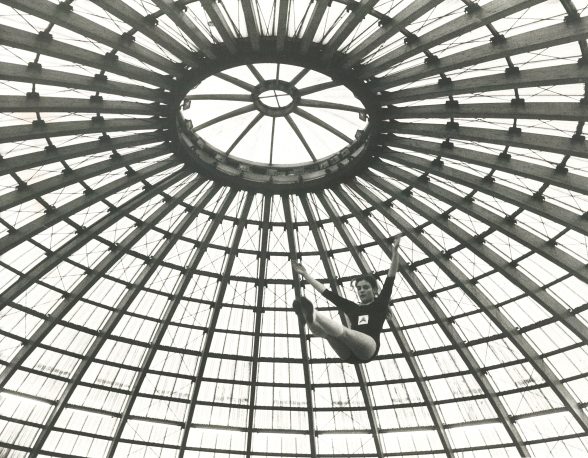

Walker Activity Dome, Newcastle-upon-Tyne – Williamson, Faulkner Brown and Partners (1963-65)

The Walker ‘flying saucer’, otherwise known as the Lightfoot Sports Dome, is one of the earliest, radical designs for leisure centres in the UK. Built without a pool, to cater to ‘dry-land’ sports and recreational activities, at the height of its popularity it was attracting 3,000 local users and visitors per week. As well as community sport, the centre has also hosted religious ceremonies, political rallies and international netball, badminton and volleyball tournaments.

The building was designed by Williamson and Faulkner Brown & Partners and strongly inspired by Pier Luigi Nervi’s Palazetto dello Sport (1957) in Rome, Italy. At the time of its opening, commentators complemented ‘an elegant structural celebration…a skeletal temple for sport and other events’. The dome is composed of 36 laminated timber arch ribs, intersected by concentric timber purlins that support a ring beam and oculus at the building’s apex. This structural system allowed for an unobstructed internal diameter of 61 metres, becoming one of the largest domes in Europe at the time of its completion, alongside one of the country’s first sports centres. The building was originally clad in reinforced fibreglass panels, allowing natural light to flood the main sports hall, but was later re-clad with a corrugated metal skin.

The centre was threatened with indefinite closure during the Covid pandemic, but following a community campaign and petition, was re-opened in 2021 with financial support from Sport England.

Website: https://www.better.org.uk/leisure-centre/newcastle/walker-activity-dome

Image – Sheila Halsall

Wrexham Waterworld – Williamson Partnership (1965-67)

Wrexham Baths, known today as Waterworld Leisure and Activity Centre, was constructed in 1967 to the designs of F. D. Williamson and is believed to be the only hyperbolic paraboloid roof in Wales, covering an area of approximately 50 x 50m beneath. Its glazed east elevation looks out assertively over the adjacent A5152 and roundabout, while its west elevation contains a series of barrel-vaulted volumes that step up towards the pointed apex of its roof. The interior has been altered by renovations in 1997 and 2017, yet despite some infilling under the roof, the constituent spaces are broadly the same, and the roof remains the dominant feature, rising and falling dramatically above the flumed pools.

Following fears that the centre would be demolished due to falling revenue and rising maintenance costs, an attempt was made in 2014 to get the building listed. Cadw (the Welsh Government’s heritage body) refused its designation on the grounds that the building had been ‘altered too significantly to be considered as an exemplar building of its type.’ However, the roof – the key feature which provides its interest – remains as originally designed. So too does the distinctive, main elevation to the south-east. Waterworld Leisure and Activity Centre is still in use today with no formal proposals put forward for its closure. However, Wrexham Council has expressed long term plans to reorganise the county’s leisure services and has looked into building a new facility elsewhere in the city.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.