This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

December 2012 - Balfron Tower

Laura Chan

The tabula rasa caused by the Blitz allowed the London County Council (and later the Greater London Council) to embrace the ideal of concentrated living, an anti-utopian model. Over the course of the 1950s to the 1970s, modern architecture spawned Brutalism, an aesthetic that was adopted by Poplar in the East London borough of Tower Hamlets, with Balfron Tower and its neighbouring Robin Hood Gardens estate. Commonly dubbed the “younger sister” of Trellick Tower, Balfron Tower is due for renovation next year, before which residents will have to vacate their properties. Designed by Erno Goldfinger and built in 1967, Balfron gained Grade II listing in 1996.

Goldfinger intended to underscore fluid movement in both towers by separating the services shaft from the main residential block and connecting them with suspended walkways or ‘streets in the sky’. With these raised walkways, Goldfinger sought to construct a romantic image of moving relationships, chance encounters and neighbourliness; a core ambition of Brutalism, further demonstrated by its structural honesty in the continuation of materials from interior to exterior.

Designed as an ‘ordered shell’, Goldfinger’s towers play a vital role in what he called ‘the human drama’. Like dancers, Goldfinger saw people as ‘time and space bound’, always enclosed by space, even if this sense of enclosure was conveyed by the sky. Writing extensively on the emotional effect of architecture, Goldfinger suggested that we are aware at some level of the way space encloses, that “you are in the street even if you are out of doors”.

Within his high-rises, human movement stops in waiting for the lift – and as Balfron only has two, people are often subjected to long delays. But once inside, the building takes over the dance. Upon entering, the vertical ribbon windows indicate the movement inside the services tower, of the up and downward motion of the lifts. When the desired floor is reached, the horizontal glazing corresponds with the direction of travel across the walkways leading to the dwellings. In this way, the building can be seen as more than a passive receptor for circulation, as it echoes the movement of the body.

In 1968 Goldfinger moved into flat 130 on the top floor, where he and his wife hosted parties fuelled with champagne, where residents were invited to discuss their flats and how they could be improved. Equipped with this knowledge, Goldfinger went onto design the taller and more famous Trellick Tower in West London. As such, the spatial design of Trellick is a further continuation of inhabitants’ movements. Doors slide into walls, rooms partition into different spaces and windows rotate for cleaning – an appropriation of space is acquired by both body and architecture in a dynamic display; the dance of the everyday.

Having lived in Balfron myself in 2010, I know all too well the downsides of living in a 1960s concrete high-rise: cockroaches live behind the concrete panels; the complex water system means you never quite know where the leak in the toilet is coming from; when both lifts break down there’s a long walk ahead of you. Maintenance issues aside, it was an absolute joy to live on the twenty-first floor of the magnificent Balfron. From this height, London was in the cup of my hands, my eye-line at the same level as the horizon.

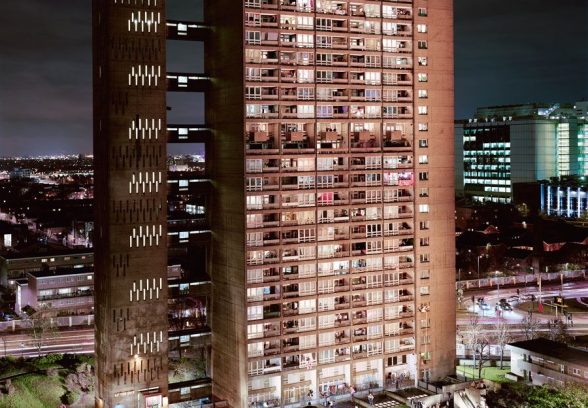

While living there I took part in Simon Terrill’s grand photographic project involving Balfron and its residents. The artist-in-residence used a large-format camera and flooded the tower with stage lighting, signalling when each shot was being taken with sound cues. He explains, “Each exposure lasted for 10 seconds and so with the opening of the lens, a strange stillness came over the building as movement would result in blurred erasure and those present needed to be stationary in order to remain visible.”

Terrill captures Balfron Tower in a glorious eerie hue, and when looking at his work I hark back to the days when I used to wait for the lift, before the dance had begun – for it to take me up, for my journey’s end was only reached when I’d crossed the twenty-first street in the sky.

Laura Chan writes about architecture and has written for Building Futures; Building; Dezeen, London Design Festival Blog; The Urban Design and Planning Journal and Address Magazine. Undertaking extreme tramps around London to encourage the flow of her prose, Laura explores the process of walking and its implications on the built environment and the written word.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.