This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

October 2013 - Wood Green Shopping City, London

by Otto Saumarez Smith

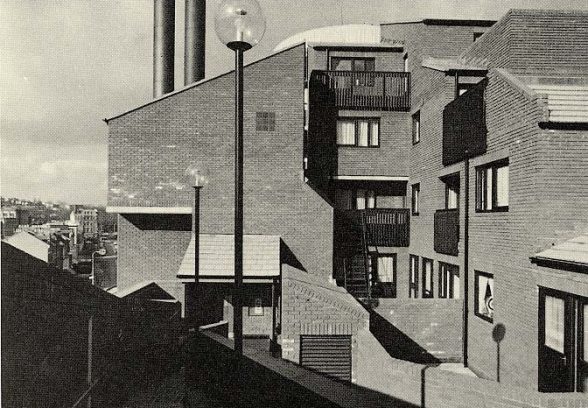

Traveling northwards through Wood Green’s low-rise Victorian suburbia, it is a shock to come upon the massive scale of Shopping City (1976-81), which looms into view, a vast red brick colossus. It rises up on both sides of the road, the two parts linked by a bridge. The first floor is cantilevered out to create an arcade at street level, increasing the feeling of passing through a canyon. Shopping City is a megastructural mélange, using three million Southwater bricks, over a fourteen acre site, to house 500,000 sq ft. of shopping space, a seventy stall market hall, car parking for 1500 cars and on top of it all an incongruous village of 201 pitched-roofed houses and flats.

The scheme’s history dates back to the 1965 creation of the Greater London Council, and the amalgamation of three north-London boroughs into the new Haringey. Wood Green was to be reinvented as a ‘Heart for Haringey’, one of a number of new suburban centres intended to counteract the magnetic pull of Central London. Many of the features of the sixties plan, such as a ‘minirail’ and the diversion of the A105 to make possible the semi-pedestrianisation of the high street, would become victim to the worsening economic climate. Nevertheless, the council held to the sixties vision with an unusual tenacity. When Shopping City was completed in the early eighties, it was one of the very last physical manifestations of the ambition towards a colossal scale that characterizes sixties urbanism.

The architects of Shopping City were Sheppard Robson & Partners, amongst the most consistently impressive of post-war British architectural practices. They were especially prolific in building for higher education, notably at Churchill College, Cambridge (1958-68) and Brunel University (1965-71). They already had experience in building a central-area shopping centre with the Pavilions (1967-76) at Waltham Cross. Within this oeuvre they had developed a house style characterized by the robustness and materiality of Brutalism, but tending to avoid that style’s more expressionist flourishes. At Wood Green they redeployed this house style, with its subdued and limited vocabulary. The structure is a partially exposed reinforced concrete frame, clad in red brick and subtly detailed with timber and bronze anodized aluminum.

The way in which the architects approached this project’s tremendous scale is instructive. Despite its marked horizontality, Shopping City has an almost picturesque massing, with each element visually distinct, and clustering upwards to a crescendo. In this it contrasts to an earlier British example of a shopping centre in neighbouring Brent Cross (1976) by the Bernard Engle Partnership, which follows American models in being an enormous inward looking box. It also contrasts to the malls that came later, which, following the example of Hillingdon Civic Centre (1973-8), attempted to mitigate their vast bulk through a pastiche of gables, belvederes and cupolas, such as the classic early example of Ealing Broadway Centre (1979-85) by Building Design Partnership.

The ‘village’ on top of Shopping City is one of the project’s more outré features; an expression of a ‘layer cake’ approach to building a city. Geoffrey Copcutt’s Cumbernauld town centre (from 1955) had pioneered the idea with its ‘penthouses’, whilst a more local precedent was Dry Halasz Dixon Partnership’s Page High scheme (1976), also in Wood Green. At Shopping City the architects made every effort to disguise the fact that the housing is above ground at all, with all of the low-rise, pitched roof homes huddled together and looking inwards on to a series of landscaped courts.

Shopping City, developed in partnership by the council and Electricity Supply Nominees and Unilever, is one of many central-area redevelopment schemes British cities initiated through private-public partnerships from the late fifties onwards. Taken together, they are amongst the least happy monuments of post-war British modernism. Few would disagree with Colin Buchanan’s judgment that, ‘I do not know of one of these projects which is not a disappointment when visited, and which does not fill one with regrets at the lack of quality in design and finishes, at the brashness and the stickers, at the loss of the sense of intimacy and service which the older shops offered, and even at the goods which are sold.’

To say that Shopping City is an exception amongst these schemes is not necessarily high praise. Certainly it remains questionable whether such gargantuan scale of development is ever justified in a city context. There was also a naivety in the hope that a shopping mall, with its lack of public space, could ever function as the ‘heart’ of a community as was hoped. Nevertheless, Sheppard Robson succeeded at Wood Green in making a virtue of an aesthetic of scale through a design that exhibits both elegant detailing and a bold élan in its conception. The practice shared with some of their contemporaries, such as Chamberlin, Powell and Bon and Building Design Partnership, an ability to exploit the dramatic potential and sheer ferocious thrill of really big projects.

Photographs courtesy Sheppard Robson

Otto Saumarez Smith is an architectural historian. He is currently studying for a PhD at St John’s College, Cambridge.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.