This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

© Art + Christianity

This Holy Week, we shared our Head of Casework Clare Price’s favourite crosses on our @C20Society Social Media channels. Here’s a round up of all the ones that were featured.

Kelham Rood, St John the Divine, Kennington, London

A peripatetic rood. Inspired by the horrors of the artist’s 1WW service, it originally stood on an arched rood beam in Kelham Hall Chapel (Notts), home to a radical theological college founded to training those from humble backgrounds. Relocated to Milton Keynes in 1973, and now on permanent loan to St John’s

The figures in this rood (group of Christ on the cross, his mother Mary and St John) are life sized. Designed by Charles Sergeant Jagger in 1929, having been commissioned by the Society of the Sacred Name (SSM), for the new chapel at Kelham Hall, Nottinghamshire (built 1927-8). The chapel designed by P.H. Currey and C.C. Thompson, is considered to be a very progressive design for the period, being an almost square space allowing the community to gather around the altar. Kelham housed a theological college set up to train clergy without an Oxbridge education and missionaries who were sent around the world. It played a particularly important role after the First World War in accommodating those inspired to join the priesthood from the rank and file in the trenches who were not served by the existing colleges.

The SSM left Kelham Hall due to a reduction in their numbers and moved to Willen Priory in Milton Keynes in 1973, taking the rood with them, where it was set up in the garden. Kelham Hall, which is a Grade II* listed building designed in 1857 by George Gilbert Scott, became the offices of the local council before being converted into a hotel, the chapel being retained as part of the hotel’s wedding offer.

© John East

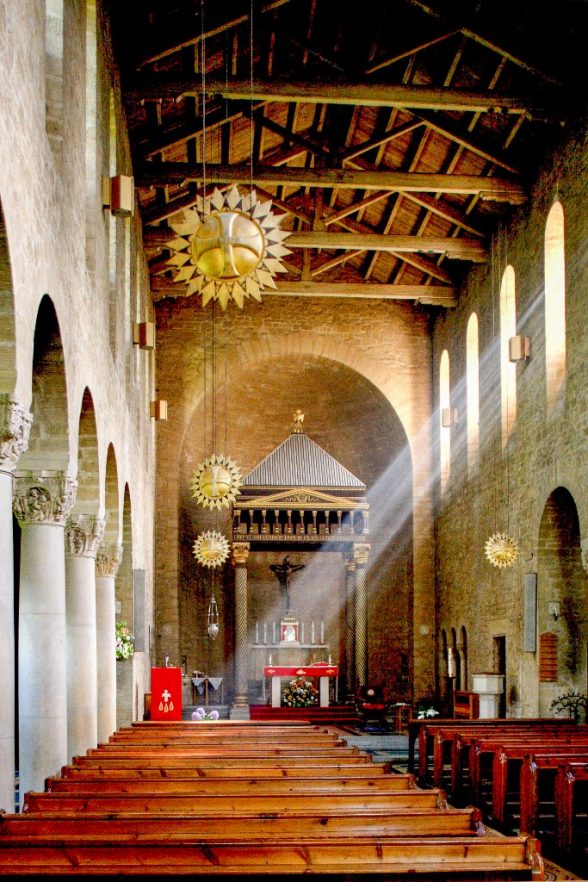

Our Lady & St Alphege Roman Catholic Church, Bath

Scott described this church as a ’little gem’ and it certainly is. Based on an Early Christian basilica in Rome, it is has the most beautiful fittings specially designed by Scott including a Cosmati pavement in lino and these lovely gilded sunburst light fittings. The crosses here are the symbol of St Alphege.

The church was the brainchild of Dom Anselm Rutherford, a Benedictine monk from nearby Downside Abbey, who was a scholar of the early Christian church and having a practical interest in architecture was intent on constructing a building that explored his research in bricks and mortar. Giles Gilbert Scott was building Downside’s church nave at the time was the obvious choice as architect. In 1927 the first plans were produced and every detail of the decoration and furnishing meticulously and carefully planned by Scott to maintain the architectural integrity of his design. Adding references to the dedication to St Alphege was a challenge: a local Prior and later Archbishop of Canterbury, he was purportedly pelted to death with mutton bones. Scott opted for scenes from St Alphege’s life carved on the nave arcade capitals, as well as the cross symbol on the gesso light fittings manufactured by Watts & Co.

Now Grade II* listed it is recognised as being of great beauty, despite the available funds never stretching to the planned campanile which would have been the crowning glory of the building. The C20 Society have recently been consulted on the conservation and renovation of the remarkable floor, made of ‘ruboleum’ a form of lino, each piece cut individually to resemble the marble pavement in Santa Maria in Cosmedin in Rome, which was its inspiration.

© John East

Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King, Liverpool

William Mitchell’s 3 incised, interlinked crosses adorn the bell tower of the RC Metropolitan Cathedral, capping this Liverpool hill with a depiction of another hill: Calvary. The largest and most prominent cross is garlanded with the Crown of Thorns symbolising Christ the King, the cathedral’s dedication.

Liverpool is unique in having two 20th century cathedrals, united by being on the same street (appropriately called Hope Street) and by the strange fact that the Anglican cathedral was designed by a Roman Catholic and the Catholic cathedral by a non-conformist. The Roman Catholic Cathedral of Christ the King was designed by Frederick Gibberd in 1962-7 and is listed at Grade II*. The bell tower with the inscribed Mitchell crosses forms a strong vertical motif announcing the entrance sequence into the circular cathedral. It houses four bells, one for each of the gospels, and Mitchell repeated this metaphor on the fiberglass main entrance doors to the cathedral which are decorated with the symbols of the evangelists. The cathedral itself was a pioneering design, taking the ideas of liturgical reform movement that dominated the thinking of the Roman Catholic church in the postwar period and realizing them in this huge circular space. The early realisation of these ideas means that not only is the altar central, but that the perimeter is filled with chapels for separate devotions: both ideas that were abandoned as the century progressed. Crowned by a luminous lantern of dalle-de-verre glass, the cathedral is known for its high quality art works.

As well as having visited the cathedral as part of the Society’s AGM in 2014, the casework team have been involved in consultation on the restoration of the dalle-de-verre lantern, the bronze doors (also by Bill Mitchell) and a Conservation Management Plan for the entire cathedral in recent years.

© John East

St. Paul’s Roman Catholic Church, Glenrothes, Fife

Justifiably famous, this elaborate 12ft tall metal cross is by Benno Schotz, the celebrated Scottish/Estonian sculptor. Schotz filled this work of art with detail. Central is the crucifixion and the traditional rood figures we saw depicted in the Kelham ensemble of Mary and St. John. Surrounding this group are the symbols of the entire Passion including the scourge, nails and spear. At the top the cock crowing after Peter’s denial – at the base, the Pieta. It is the entire story of Holy Week in sculptural form.

The cross hangs on the east wall, focussing attention on the altar of this ground-breaking church of 1957. Not only was St Paul’s the first collaboration by Isi Metzstein and Andy MacMillan for the internationally renowned practice of Gillespie, Kidd & Coia, it was also the first church in Scotland not to have a traditional rectangular plan. It is recognised as being the most important early post-war church in Scotland by its Category A listing.

Innovative in form, the strength of this sacred space is its simplicity: the bare walls forming a backdrop to the devotional artworks by Schotz, of which the cross is just one. Equally important to the interior here is the interplay of light. Isi Metzstein commented on this aspect, saying: ‘The church at Glenrothes was the first church of the new generation and was a significant change in direction. The concept, or basic principle, is about light’.

© Matthew Steele

Langley Cross, All Saints and Martyrs Church, Manchester

The enormous Langley Cross dominates All Saints and Martyrs Church. Designed by Geoffrey Clarke, who has a Coventry connection as he is probably best known for his Cross of Nails in Coventry Cathedral. Instead of the traditional figure of the suffering Christ, Clarke depicts martyrdom here with shapes that suggest modern weapons, perhaps a rifle?

All Saints and Martyrs church by Leach Rhodes and Walker appears to have been designed around the cross which dominates the internal space of this 1964 building. It is difficult to appreciate the sheer scale of this rough-cast aluminium sculpture from the photographs – it stands at 37 feet tall with a width of 20 feet. Clarke was a well-established sculptor by the 1960s, famous not only for his involvement with the artwork for Coventry Cathedral but also for the 1952 British Pavilion exhibits at the Venice Biennale, together with Lynn Chadwick, Reg Butler and Kenneth Armitage: a group of artists dubbed ‘Geometry of Fear’ sculptors by Herbert Read.

© C20 Archive

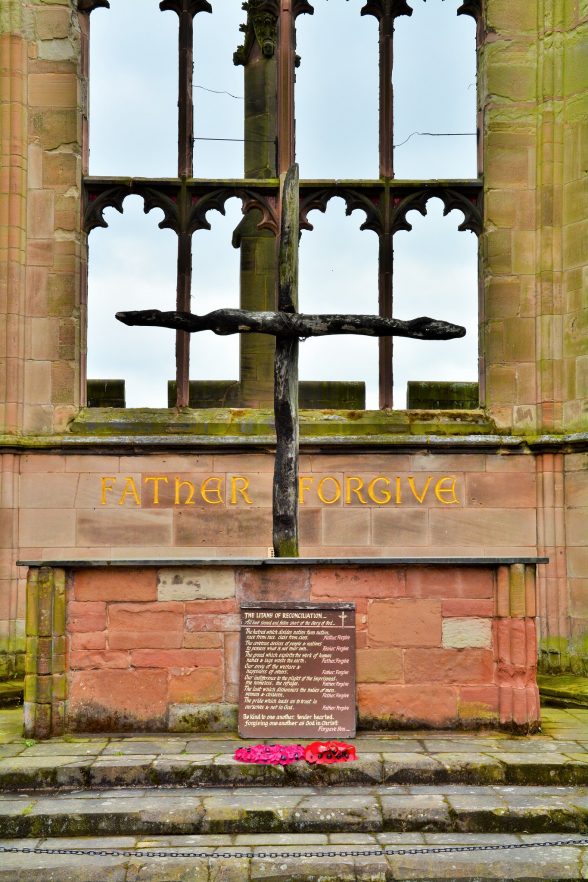

Charred Cross, Coventry Cathedral ruins

The most poignant of all, perhaps – not a work of art by a famous artist but no less affecting. It was formed of two charred roof timbers pulled from the devastation of the 1940 firebombing of the medieval Coventry cathedral, bound and placed where the altar had been (although replaced by a replica in 1964). A symbol of hope and reconciliation: ‘Father forgive’ is inscribed on the wall behind.

The decision to rebuild was made the very next day after the building was burnt to the ground in November 1940. This resulted in a closely fought architectural competition in 1950-51 to find a design that would complement the original building. Coming at a time of a great deal of re-thinking of the form and function of church architecture, Spence’s chosen design was considered too traditional by many architects. The retention of the medieval ruins were fundamental to the realization of the new cathedral. They were seen as a symbol of remembrance and hope for the future.

Another cross came from the ruins: that of the Cross of Nails formed of three medieval nails left by the fire. Geoffrey Clarke’s interpretation of this was made for the new cathedral. More crosses were made from nails from the burnt roof timbers and sent around the world. One of these was given to the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church in Berlin, which suffered a similar fate to Coventry cathedral (at Allied hands) and also built anew next to the ruined building.

© John East

Easter Sunday: Coventry Cathedral

The ultimate symbol of rebirth. Set at right-angles to the charred remains of the old arose Spence’s stunning new space. A pilgrim journey leads you through the ruins into the new: experienced as if one cathedral. It is dominated by Graham Sutherland’s powerful reredos tapestry depicting the risen Christ, ‘Christ in Glory in the Tetramorph’ – the Tetramorph incorporates the symbols of the four evangelists.

Coventry Cathedral is a Grade I listed building designed by Sir Basil Spence and built between 1954 and 1962. It was a controversial competition win for Spence, and the cathedral has had a mixed reception, but the impact of this building when experienced in person is enough to make you instantly forget the background story. This tapestry alone is quite remarkable. When the C20 Casework team went to Edinburgh to see the Spence archive (a SAHGB day) we were privileged to be able to see the correspondence that Sutherland had with Pinton Freres when they were weaving the tapestry, and to get a feel for the problems of manufacturing such a colossal piece, as well as the many photos in the collection showing the various stages of construction of the cathedral building.

The C20 team have also been working with the cathedral recently as they put together a Conservation Management Plan to appreciate the heritage of the building and we have been in consultation on their projects to improve facilities for Coventry City of Culture. The Society’s AGM will be held in Coventry next year.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.

Comments