This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

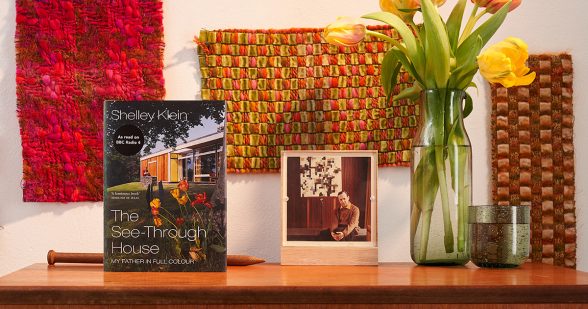

Next month, in collaboration with Vintage Books, we will be giving away a free copy of Shelley Klein’s new book: The See-Through House. Competition rules will be announced soon but in the meantime, here’s a bit more about the publication and an extract to read over the weekend…

The See-Through House is a book about saying goodbye to a much-loved family home. It is also a very funny account of looking after an adored yet maddening parent and a piercing portrait of the grief that followed his death.

Shelley Klein grew up in the Scottish Borders, in a house designed on a modernist open-plan grid; with colourful glass panels set against a forest of trees, it was like living in a work of art.

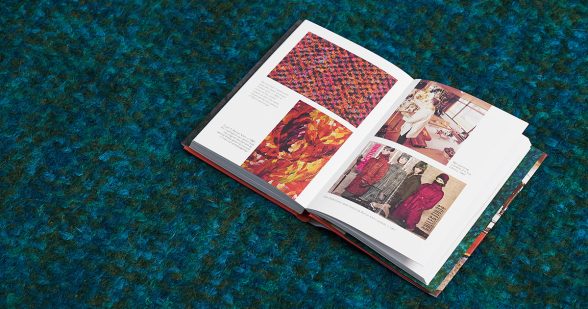

Shelley’s father, Bernat Klein, was a textile designer whose pioneering colours and textures were a major contribution to 1960s and 70s style. As a child, Shelley and her siblings adored both the house and the fashion shows that took place there, but as she grew older Shelley also began to rebel against her father’s excessive design principles.

Thirty years on, Shelley moves back home to care for her father, now in his eighties: the house has not changed and neither has his uncompromising vision. As Shelley installs her pots of herbs on the kitchen windowsill, he insists she take them into her bedroom to ensure they don’t ‘spoil the line of the house’.

Threaded through Shelley’s book is her father’s own story: an Orthodox Jewish childhood in Yugoslavia; his rejection of rabbinical studies to pursue a life of art; his arrival in post-war Britain and his imagining of a house filled with light and colour as interpreted by the architect Peter Womersley.

A book about the search for belonging and the pain of letting go, The See-Through House is a moving memoir of one man’s distinctive way of looking at the world, told with tenderness and humour and a daughter’s love.

An extract from the book:

Ever since my mother died a year ago, I have known that Beri wanted me to come back and live with him. This is not because he can’t cope on his own, for despite being eighty-five years old he is still very capable. But he’s lonely and isolated and my older brother and sister (Jonathan and Gillian) have families to look after and jobs that they can’t just up and leave, which leaves only single, self-employed, childless me.

I jump out of the van and crunch my way across the front courtyard, where Beri gives me one of his great big bear hugs. There are thirty-nine years between us, one world war, five languages and two countries, but Beri and my mother, Peggy, have given me the only two things truly worth having: love and security.

‘This is nice, isn’t it?’ he beams and I nod because it’s true. It is nice to be back, for despite leaving High Sunderland nearly twenty-seven years previously to go to university in London and despite having lived in numerous rented flats throughout the city and more recently my fisherman’s cottage in Cornwall, I still consider High Sunderland the only real ‘home’ I have ever had. I was born here and I grew up here and every year since, no matter what was happening in the rest of my life, I have spent at least one or two weeks here during the summer and every Christmas with the exception of two.

I step into the hallway and immediately breathe in a mixture of familiar smells: paprika, woodsmoke and freshly ground coffee. It is the most relaxing smell in the world. A smell that says I am back where I belong. But ten minutes later, just as I am carrying all my stuff into the hallway from the van, my mood takes a turn for the worse…

BERI: Would you mind putting those somewhere else?

SHELLEY: Why? They look nice here.

BERI: Why don’t you put them in your bedroom? If you wouldn’t mind?

SHELLEY: But they’re herbs. They’re for cooking with –

BERI: They’d be better off in your bedroom –

SHELLEY: I’m not trotting through to the bedroom every time I need a bit of thyme.

BERI: Suddenly you can’t walk a little?

SHELLEY [irritated]: What have you got against herbs?

BERI: They’re messy –

SHELLEY: They’re plants –

BERI: They’re messy plants. Except for the chives.

SHELLEY: And the chives have what going for them that the others haven’t?

BERI: They’re vertical.

SHELLEY [through gritted teeth]: All plants are vertical.

BERI: But some are more vertical than others –

SHELLEY: You’re joking, right?

BERI: They spoil the line of the house –

SHELLEY: The WHAT?

BERI [patiently, as if explaining something to an imbecile]: The line of the house.

And that was that. I knew immediately there was no point continuing to fight the herbs’ corner (or, in this case, windowsill).

For as long as I can remember, it has been understood within our family that High Sunderland is not simply a house. One close friend, Jenny, described it as ‘a Mondrian set within a Klimt’ because with its series of colourful glass panels set against a backdrop of birch and fir trees, it is like living within a work of art. Not only that, but the house, which was built in the modernist vernacular, dictates how one should live, what one should pay attention to and what one should ignore. It is a deceptively simple structure yet ultimately a highly complex amalgamation of ideas and ideals, a timepiece and a time machine as well as a combination of two men’s ambitions: that of the architect – Peter Womersley – whose first proper commission this was, and a young Yugoslavian émigré to Britain – my father – who commissioned the project. Over the next fifty-six years Beri was to become so attached to High Sunderland it was almost impossible – to my mind, at least – to separate the two things out from each other.

My father was the house.

The house was my father.

Built in the late Fifties, High Sunderland makes no apologies for looking towards the future rather than gazing nostalgically towards the past. Like Beri himself, whom an acquaintance once noted was ‘far more modern than any of his children’, High Sunderland is more up to date than most contemporary housing. As you approach it from the driveway through a thick forest of pine trees, it appears at the top of the hill as a low-slung series of interconnecting boxes and grids. Planes of both clear and coloured glass are interlaced with white, horizontal beams that in their turn are balanced between sections of ridged Makore wood that because they don’t lie flat, lend each panel a tactile quality normally reserved for fabric. At night, when the internal lights are switched on and you are standing outside, the effect is of a light box effortlessly floating above the ground while during the day the various panels of yellow and green have all the luminosity of boiled sweets. But although as an adult I appreciate the unique beauty of High Sunderland, this was not always the case.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.

This sounds a wonderful book. As the daughter of a french emigree, now 96, a lot of this rings true.