This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

We were saddened to hear about the death of C20 Member Stephen Marks. This is a republication of an article from one of our 2013 Magazine issues featuring images of what London might have looked like if the radical scheme for passenger distribution had gone ahead, that were sent to us by Stephen from his time in the Westminster Planning Department.

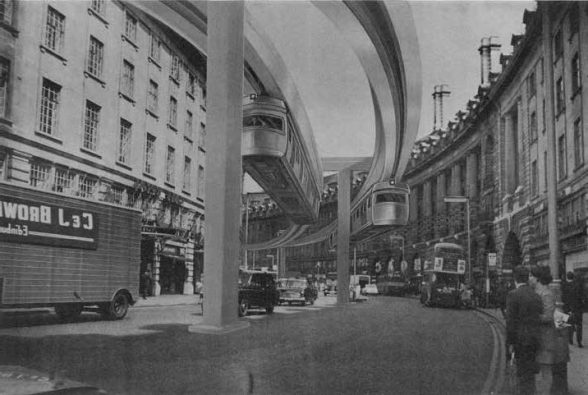

No, it’s not a film set, it’s Regent Street as it might have been . These amazing images come from a document produced by the GLC Department of Highways and Transportation in 1967 (the same year the Civic Amenities Act gave councils the duty to designate conservation areas). We were sent a copy by C20 member Stephen Marks, who took up a conservation post in Westminster’s Planning Department just as this radical scheme ‘for passenger distribution in Central London’ was being considered.

These were definitely very different times: at a five-day planning inquiry in 1972, Marks (acting for Westminster Council) helped to see off a scheme by Richard Seifert to demolish a whole block of Piccadilly. This included the now Grade II* listed bank by W Curtis Green at No 63, a building only fifty years old at the time. There were also proposals for a ‘grandiose redevelopment of Piccadilly Circus and surrounding streets, involving a new deck level, with the street at ground level reduced to function as a service access, and Eros raised onto the new deck.’

It’s no surprise that this ‘would have involved colossal loss of historic buildings and familiar townscape, and colossal expense’, and fortunately the scheme was abandoned. Where did the monorail idea come from? Was there one particular transport enthusiast seriously pushing for this sort of solution?

Someone clearly thought it was worth commissioning a report looking at examples from across the world, including at Disneyland (1959) and Seattle (built for the World’s Fair in 1962) by the German Alweg company, the Wuppertaler Schwebebahn (suspension railway) in Germany, running since 1901, the Westinghouse Expressway in Pittsburgh, and developments by the French SAFEGE consortium. But the problems were enormous (and you might say obvious): how to accommodate large foundations, how to arrange access from street level, what to do about noise, vibration, loss of light, invasion of privacy, rain dripping from the structure, oil from the vehicles… and, not least, how to fit rails with a rather large minimum radius of curvature round the tight bends of Oxford Circus and Piccadilly Circus.

The report is quietly damning throughout, noting that ‘the visual and acoustic effects of any new system proposed must be much more fully investigated if the vital urban character and quality are to be maintained.’

Stephen Marks stayed at Westminster and became a Planning Inspector in 1976 (he was Inspector for the Mies van der Rohe proposals for Mansion House Square), and notes that, by the time he left, ‘the attitude of the committee… had moved from allowing a proposal unless there was a good reason to prevent it, to refusing it unless there was a good reason to allow it.’ That’s some turnaround.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.

Comments