This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

November 2022 - Aiton & Co Factory Offices, Derby

Image courtesy of Lynne Walker

Factory Offices for Aiton & Co, Derby

Norah Aiton and Betty Scott, 1931

Here are Norah Aiton (1903-1988) and Betty Scott (1904-1983) at the drawing board of their architectural partnership in Sloane Street, Chelsea in 1931. This photograph was taken to mark the completion of their Factory Offices in Derby, a building which is little appreciated as the first modernist industrial building in Britain. It is built almost entirely of steel, glass and reinforced concrete with steel-framed construction, reinforced concrete floors and horizontal bands of metal-framed Crittall windows glazed continuously on all sides. Norah Aiton commented: “Nothing like the Derby office has been seen before in England.”

Aiton and Scott formed part of the earliest generation of women who in the 1920s and 1930s trained in architectural schools, only recently opened to female students, and embraced professionalism. At Girton College, Aiton had given up mathematics to attend the Cambridge School of Architecture (1924-6) and later the Architectural Association (1926-9) where she met her future partner, Betty Scott. The latter’s planning ability and graphic skills made her a student star (1923-8), winner of the Public School Entrance Scholarship, the Second Year Prize for Art, and the Victory Scholarship awarded by the RIBA. Both travelled extensively and between them they had seen the new architecture in Germany, France, Sweden and the Netherlands, while Scott spent three months working in the New York firm of Bottomley, Wagner and White. Although not involved in the rhetoric and dogma of continental modernism, they were well-versed in the principles, practices and concerns of the Modern Movement.

On completion of their studies, they set up on their own practice, joined the RIBA, entered competitions, had their work professionally photographed, subscribed to the architectural press and had their projects illustrated in it, experienced critical reception and—distinctively—they put their own names on their practice.

Like many architects starting out, they received their first commission from family. At the height of the Depression and with an empty order book, Norah Aiton’s father commissioned a new building to accommodate and promote Aiton & Company. Founded in 1900, the firm had grown quickly and steadily but in piecemeal fashion. It manufactured high pressure, high temperature pipes used, for example, by power stations and the London Underground. Aiton looked to his daughter’s practice to produce a design which was correspondingly, and self-consciously, cutting edge and which would provide a corporate image, and indeed an advertisement, for the firm and its products.

Image courtesy of Lynne Walker

Image courtesy of Lynne Walker

Image courtesy of Lynne Walker

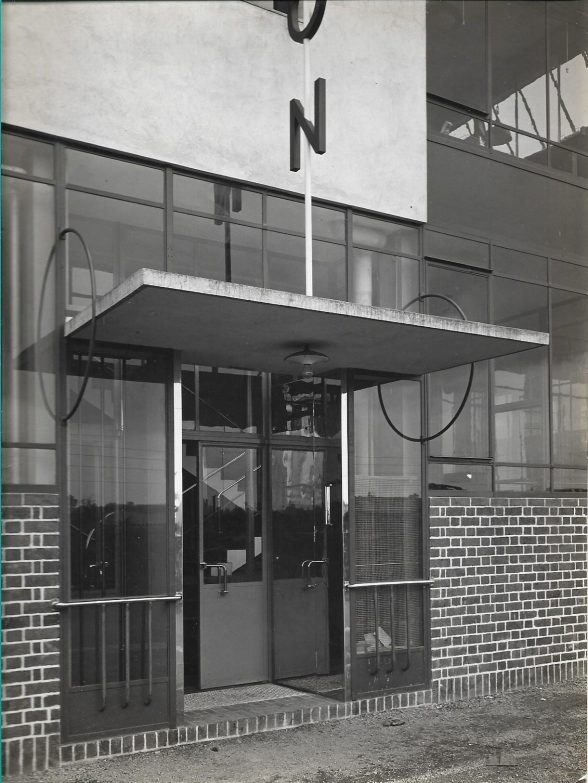

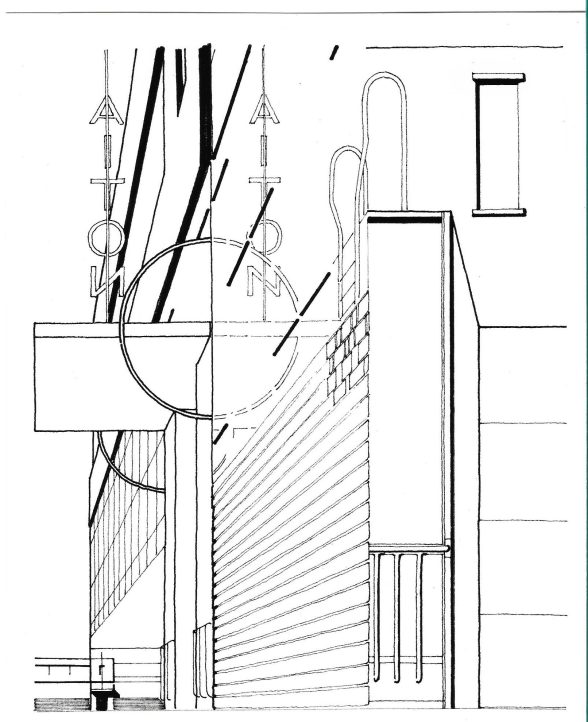

Sited hard by an arterial road on the outskirts of Derby, Aiton & Co. (f.1900). Aiton and Scott’s design is a remarkable statement of Midlands modernity. Two storeys high, clerical offices are on the ground floor, while drawing offices and executive rooms are in the floor above. The façade is dominated by a doorway signalled by a red metal vertical sign, made in a high-quality stainless steel that could take colour and was worked by welding, one of Aiton & Co.’s innovations in the pipe making industry. This played into what Aiton, who had visited the Rietveld Schröder House, Utrecht (1924) shortly after its completion, called “my version of a De Stjil colour scheme”: red vertical and jade green horizonal signs, blue brick plinth, grey window frames, and white cement and grey stucco finishes.

Image courtesy of Lynne Walker

Image courtesy of Lynne Walker

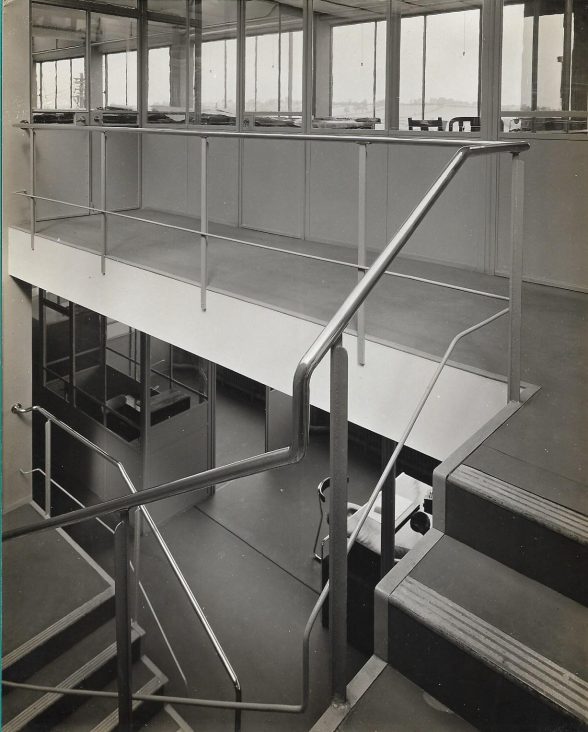

The dramatic spatiality of the staircase, carefully lit from above and below, provides a mise-en-scène which is almost cinematic in effect. A foreshadowing perhaps of Betty Scott’s later work for film companies in art direction and set design, after the Second World War. The repeated use of metal tubing in decoration, detailing and furnishing is most fully exploited in the stainless steel of the staircase.

Image courtesy of Lynne Walker

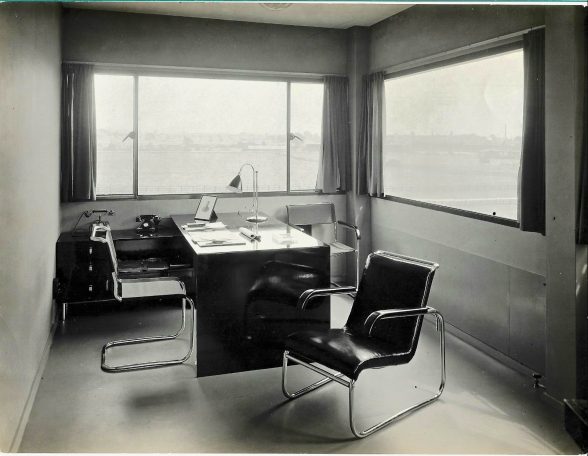

At the top of the staircase, light is borrowed from the drawing office. For the architects, the most important point of the design programme was to produce a well-lit drawing office with the least possible amount of shadow for the company’s designers, taking great pains with the technical aspects of light and shadow. In general terms, Aiton described the practice’s aims as “Air, light, and cleanliness” with their key priority the well-being of workers, who were to be inspired by the spacious accommodation and views from the generous glazing across to the greenness of the county cricket ground opposite.

Image courtesy of Lynne Walker

Image courtesy of Lynne Walker

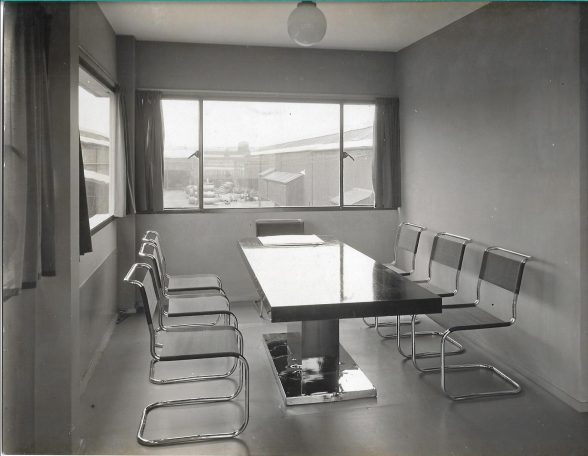

Christopher Wilks has observed that the “utter sparseness” of the interiors is similar to contemporary exhibition installations. However, the black and white photographs do not show that colour was a main feature inside as well as out. Red lino floors, grey-green walls, and steelwork with white ceilings provided richness and were carefully toned and harmonised. The furnishings such as the seating by Marcel Breuer, were straight out of the Thonet catalogue. In the boardroom, the two architects designed the board table themselves.

In a short career which began during the deepest economic crisis of the 20th century and ended with the Second World War, Norah Aiton and Betty Scott (who later used her married name Pierce when she went into film) played a key role—often unacknowledged—in modernising not only architecture but the profession itself. The place of women in British architecture at this time was widely seen to be domestic architecture, not in the design of industrial or commercial buildings, such as the Derby factory offices. However, Norah Aiton and Betty Scott refused to be pigeonholed, producing a printing works in Barnet, a crematorium in Cambridge, a church design, and a private zoo, as well as domestic architecture both modernist and in the alternative modern tradition. Their design for Aiton & Co. remains, and is now Grade 2 listed.

All photos courtesy of Lynne Walker.

Dr. Lynne Walker is an architectural historian and a Senior Fellow at the Institute of Historical Research, University of London. She has published widely on gender, space and architecture, including curating the first historical assessment of architecture in Britain designed by women, ‘Women Architects: Their Work’ (RIBA, 1984). In 2017 with Elizabeth Darling, she curated , exhibition, international conference, and related events which marked the centenary of women at the Architectural Association (1917-2017).

The Building of the Month is edited by Dr. Joshua Mardell.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.