This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

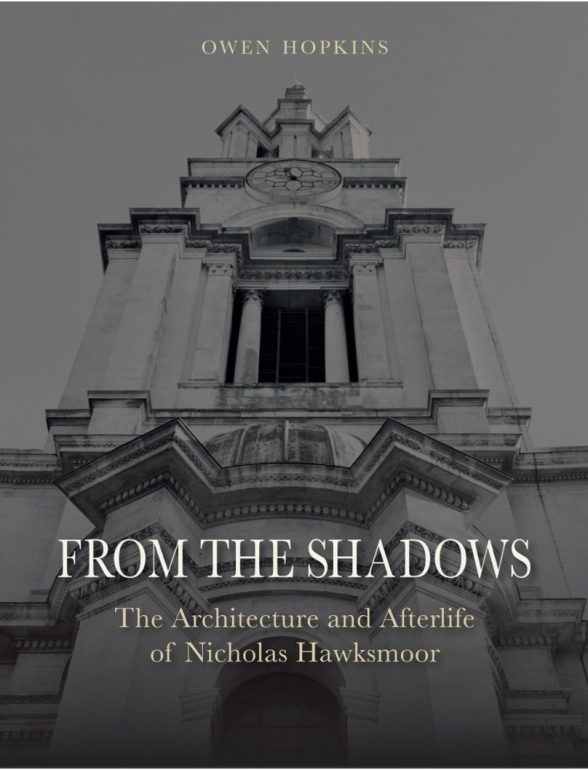

From the Shadows: The Architecture and Afterlife of Nicholas Hawksmoor

Owen Hopkins (Reaktion, 344pp, £25)

Reviewed by Catherine Croft

His dates – 1662-1736 – may be way outside our period, but Nicholas Hawksmoor, best known for his six massive Portland stone churches in London, has had a profound effect on many major C20 architects. The restoration of some of Hawksmoor’s key works has proved difficult and controversial: influencing the development of C20 conservation practice, as much in terms of the social positioning of conservation as in debates about whether and how to reinstate lost original fabric. His work has also been key to the development of psycho-geography and to shifts in our perception of urbanism, dereliction and decay. At least three good reasons, then, why the second half of this book will be of particular interest to C20 Society members.

Hopkins demonstrates how, until Kerry Downes’ 1959 monograph (which he greatly admires), there was much confusion about which works should be attributed to Hawksmoor. He was then not nearly as well-known as Wren or Vanbrugh. His current fame is a product of not just academic research, but a great coalescence of interest from a range of imaginative individuals who have responded to the physical presence of the works themselves and the myths and stories spun around them.

Hopkins’s exploration encompasses the wartime photography of Bill Brandt (he showed a man sheltering in the crypt of Christ Church, Spitalfields, sleeping in a stone coffin) and the morose late-1980s paintings of Leon Kossoff. He details the campaigns to save Christ Church and St George’s, Bloomsbury (which involved Dan Cruickshank, Colin Amery and Lord and Lady Kennett, as well as the World Monuments Fund and the Heritage Lottery Fund). Nicholas Serota’s 1977 Hawksmoor exhibition at the Whitechapel Art Gallery implied by its location that the architect was an inspiration to contemporary artists (the architect and past President of the Society Trevor Dannatt arranged for it to travel to the University of Manchester) and writings by Iain Sinclair and Peter Ackroyd have had a big impact. The latter’s Hawksmoor won major literary prizes and was a best-seller; although it was ‘only’ a novel, our past-chairman Gavin Stamp deplored ‘the sensational and mendacious notoriety’ that its gothic plot of murder and the occult heaped on his hero. Hawksmoor’s reputation has more than survived.

Hopkins is most thought-provoking in his positioning of Hawksmoor as a proto-post- modernist, and it’s interesting that his selection of post-war architects influenced by him includes a modernist (Denys Lasdun), a post-modernist (Robert Venturi) and James Stirling, who controversially moved from modernism to post-modernism, and whose No 1 Poultry faces Hawksmoor’s St Mary Woolnoth. For each of them, Hopkins believes Hawksmoor ‘became a powerful totem of a creative spirit unbound by rules or strictures’, and he also quotes Richard MacCormac’s enthusiasm for Christ Church: ‘Its great architectural gestures retain their strange potency and continue to astonish and invite my curiosity.’

I’m frustrated by his assessment that ‘for those working in the 1950s and 1960s, who looked at architecture through the lens of the failures and increasing banalities of post-war modernism, Hawksmoor appeared as a free creative spirit’, because I think we are coming to understand that the imaginations of many architects of that period were richly nurtured by a wide range of past works, as well as extensive travel. Nevertheless, he has had a crucial role as cultural catalyst, of which this book is a fine celebration.

We are still populating our book review section. You will be able to search by book name, author or date of publication.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.